In the gray mist of an early dawn a small Eskimo boy scampers down the barren beach at Shaktoolik, Alaska, and scans the horizon. Far out where Norton Sound meets the sky, he spots a freighter riding the choppy water.

“It come! The ‘North Star’ come,” he shouts triumphantly. “Moe’s comin with candy!”

Full speed, he dashes back to the dilapidated community center. His friends have been camping there for the last two nights, waiting for the boat. No point sleeping at home, taking a chance on missing anything or waking the family if the ship arrives early. The “North Star”, after all, is the biggest event of the season.

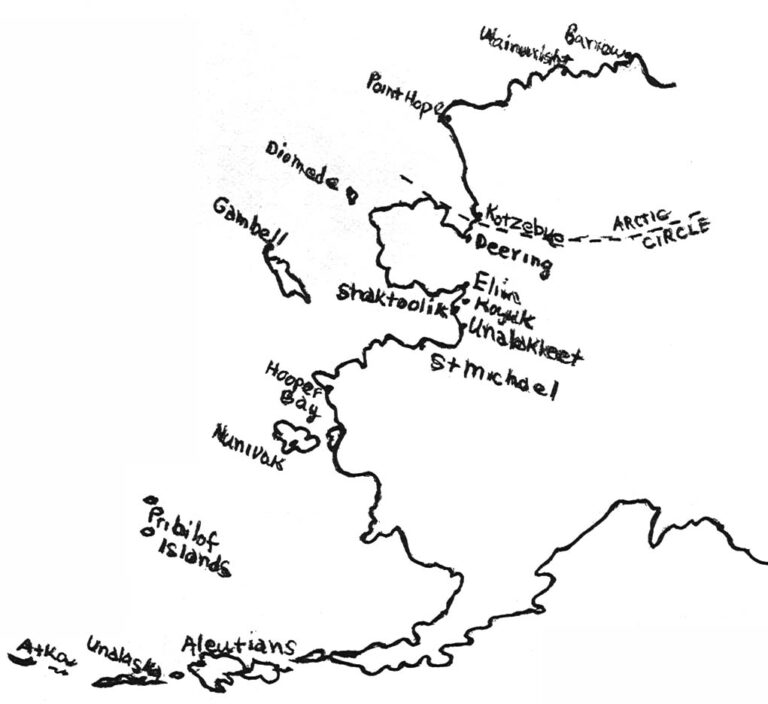

Remote villages along Alaska’s northern coast and Aleutian Chain go grocery shopping only once a year. “North Star III”, the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) supply freighter, brings the orders; braving shallow, uncharted waters and Arctic ice that few commercial carriers care to tackle.

The ship is an institution now. It was preceded by “North Star II”, “North Star I” and the “Boxer” which initiated the run in 1923. But even more legendary is skipper Cecil W. Cole, who shipped on the “Boxer” as a messboy in 1937 and worked his way doggedly through the ranks until last season he became captain of “North Star III.”

To most Alaskan villagers, he’s known simply as, “Moe” and a good friend. As far as they can see, he hasn’t changed since they first encountered him almost four decades ago – an affable bear of a man who seemed to worry more about their welfare than his own and was a soft touch for the children.

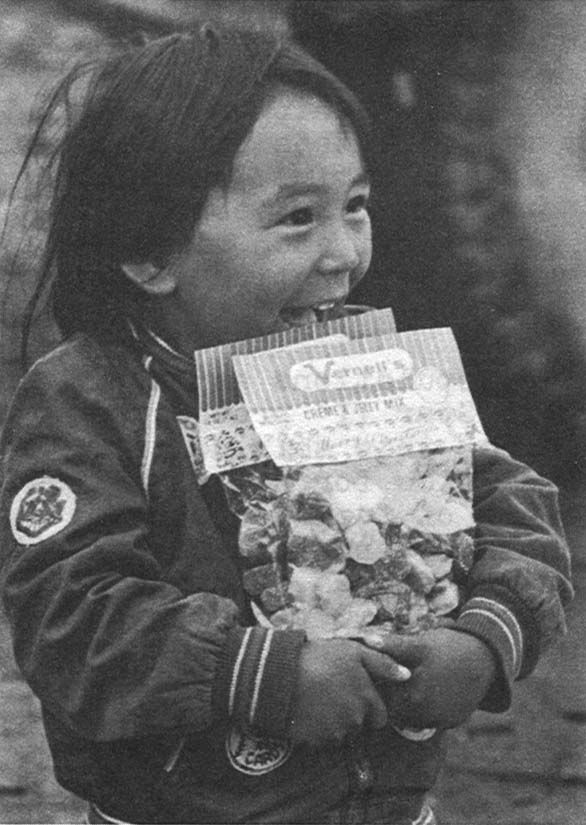

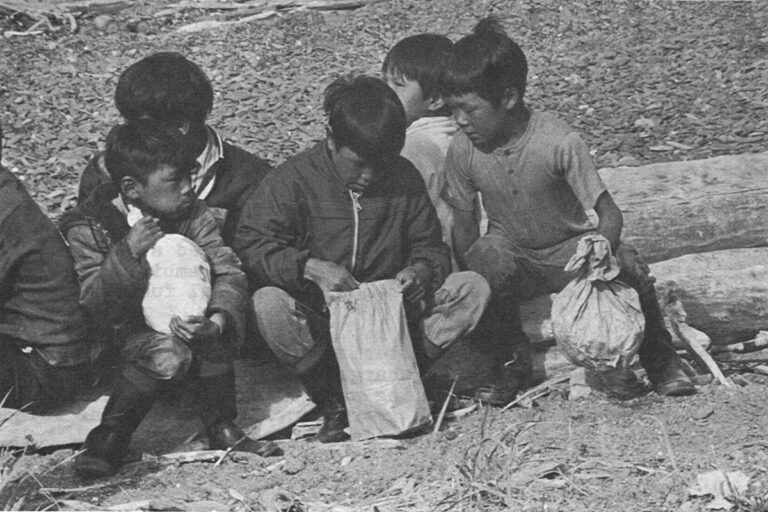

Cecil W. “Moe” Cole – watching children at Unalakleet enjoy the bags of candy he brought them.

In those days the Alaskan Eskimos, Indians and Aleuts were rated among the world’s most impoverished people and Moe could readily understand their problems. He’d come up rough himself, on the waterfront at Puget Sound.

“We never had much…never had much candy. I can remember going to the churches around Christmas time, hoping to get some…as a kid,” he recalls. “So on the Alaska run I started giving out bubble gum and red cinnamon candy. Found the kids really honest. I’d leave a million dollars worth of nickels out and never worry about them with those kids.”

Soon he began giving out oranges, toys – anything he could afford or talk someone out of – that he thought the isolated youngsters might enjoy.

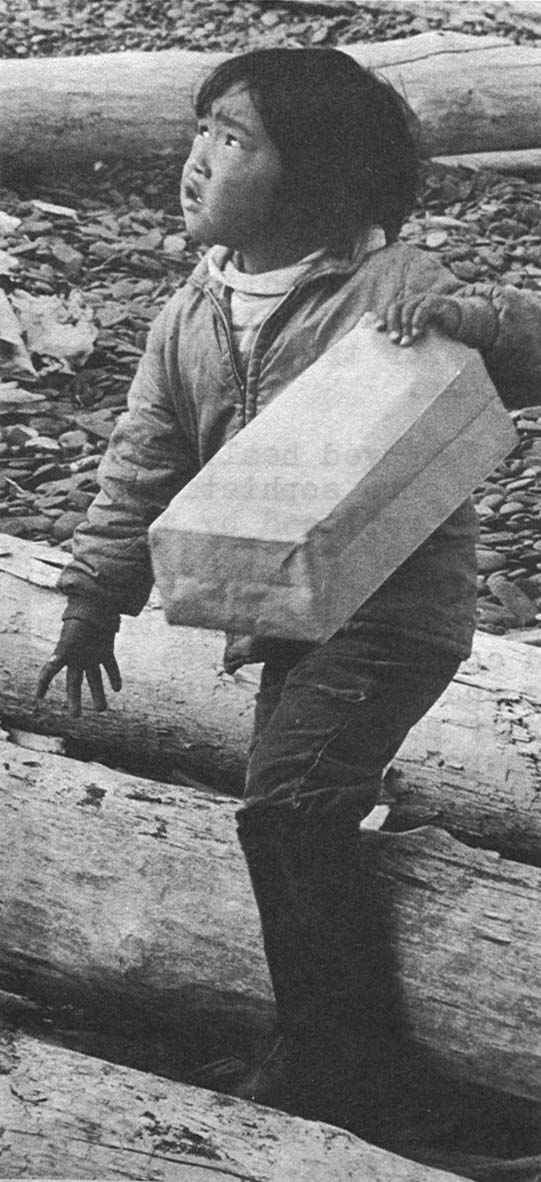

Out To Meet The Candy Man – Top Left, a little girl from Unalakleet, Alaska, clutches a present Moe has given her.

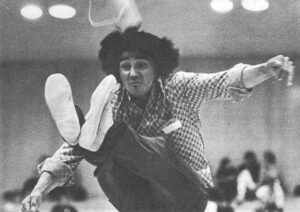

Right, a late comer hurries down the beach at Shaktoolik, hoping he hasn’t missed the fun.

Bottom Left, Shaktoolik youngsters inspect their prizes.

“One year I got a gross of mouth organs and kazoos,” he chuckles. “You’ve never heard anything till you’ve heard a village full of kids all playing kazoos. Then one time I got seven dozen baseballs. No scrambling. Made um stand in a circle and tossed them out. If the ball hit um, it was theirs.”

We’ve Got To Get In There

Over the years the function of BIA supply boats has shifted. When Moe first signed on the 350 ton “Boxer”, it was bringing staples and building materials to replace the traditional native sod huts and underground houses which had proved too efficient spawning ground for tuberculosis. In 1941 the old wooden ship was replaced by “North Star I” with a carrying capacity of 2,500 tons but needs of the native people soon outgrew it. In 1949 it was retired and “North Star II” went into action with a 5,000 ton capacity. The vessel also served as a floating health clinic, anchoring off each village long enough for traveling doctors and dentists to give natives a yearly check-up.

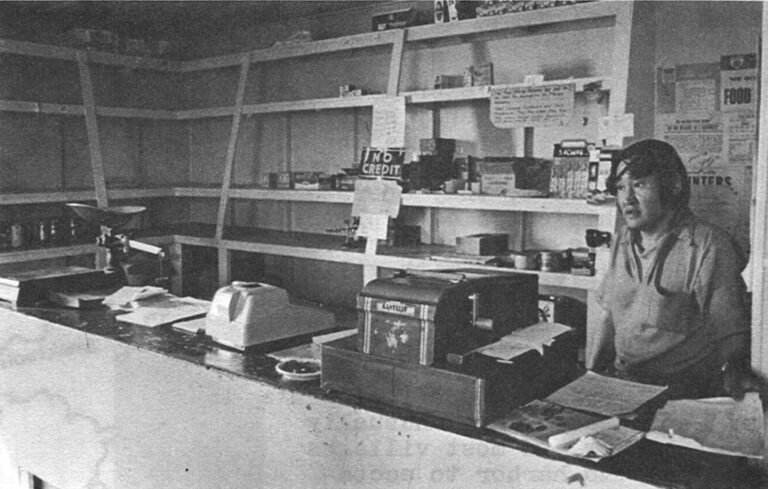

Improved health care expanded native populations and their needs became more sophisticated. By 1961 “North Star II” proved too small and was replaced by “North Star III”. Today this ship delivers fabricated buildings to serve as health clinics for newly trained native health aids; ever increasing amounts of fuel for stoves, electric generators, trucks and snow machines; and tons of groceries and consumer products for native cooperative stores. Demand is growing and “North Star’s” carrying capacity of 10,000 tons is just barely adequate to service the 65 to 70 villages that have no viable transportation alternatives.

Settlements with no airfields depend almost wholly on “North Star III” for freight and the responsibility weighs heavily on its captain.

“We’ve got to get in there,” he worried last spring when he waited three weeks off the fearsome Arctic ice pack to make delivery to the northwest coast. “We’ve got their whole year’s food supply.”

Commercial shipping companies that sometimes venture into “North Star” waters, feel no compunction to wait out rough weather or guarantee delivery. Sometimes they dump freight off at an alternate point, leaving natives to figure a way to collect it and pay additional shipping charges. Sometimes they simply write off a stop, abandoning villagers with empty larders.

The “North Star” guarantees delivery at a tariff worked out somewhat to the advantage of the native people. The operation (which costs close to $2 million in an average year) is self-sustaining, despite the fact that it runs in the most treacherous navigable waters in the world with an emphasis on service.

In addition to delivery of freight, the “North Star” crew installs bulk fuel tanks for BIA schools, other government agencies, native cooperatives and church missions. This has proved a vital service, as Alaska’s remote areas are in the midst of an ambitious electrification project which requires considerable diesel fuel to run generators.

The ship also transports materials for community building and surplus USDA commodities at no charge, and offers a low rate for shipping the products of fledgling native industries – craft items such as woven grass baskets and ivory carvings, as well as reindeer meat, skins and the produce from Aleutian sheep ranches.

The ship’s crew provides a lot of emergency service such as repair of radio equipment and heating plants. In addition, they operate the ship’s two caterpillar tractors which can be sent ashore to help with village building and moving projects.

Low Water and Sandbars

The waters off Alaska’s north coast are unusually shallow and most villages have no harbor to accommodate the “North Star’s” 28 foot draft. On the vessel’s average run there is only one dock it can tie up at. Usually heavy equipment and freight must be lightered in – sometimes as far as 80 miles round trip.

The “North Star” was the first Alaskan freighter to find a practical solution to this problem. She carries four World War II LCM lighterage units (landing barges), each capable of carrying 35 cubic tons. Despite the fact there is only one high water period in 24 hours during the summer tides, the LCM crews manage to navigate an astonishing number of sandbars and reefs to make delivery.

The coming of the “North Star” is welcomed by many jobless villagers as a source of income. Local people are employed in lighterage and long shore operations and native hire is now mandatory for filling many crew positions.

Realistically, however, it would seem the “North Star’s” days are numbered. She is a 27-year-old vessel, one of two World War II Victory ships built with a diesel main engine instead of steam. Many of her replacement parts today must be hand-tooled in her machine shop and more replacements are needed every year.

Another problem is that the ship is not containerized.

“I think we must be the last hand-stowed freighter in the world, unless there’s some Ding-a-ling running around we don’t know about,” observed one crewman who had previously shipped on ultra-modern vessels. “It takes a containerized ship only a fraction of our loading time to get underway.”

Settlements with no airfields depend almost wholly on “North Star III” for freight and the responsibility weighs heavily on its captain.

“We’ve got to get in there,” he worried last spring when he waited three weeks off the fearsome Arctic ice pack to make delivery to the northwest coast. “We’ve got their whole year’s food supply.”

“It would cost us a lot less to operate a modern vessel,” admitted a “North Star” maintenance man. “But by the time we got an appropriation for one through Congress, our building plans would be obsolete.”

Eventually, it’s hoped, private enterprise will take over the “North Star” functions. If federal settlement of the native land claims generates enough investment capital, perhaps local barge lines will develop to lighter freight from large, containerized vessels through shallow, local waters. But as things stand now, Alaska’s isolated coastal population would be hard pressed if the “North Star” didn’t make her run.

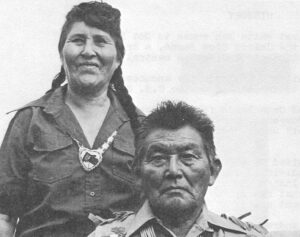

The situation was well stated by Henry Shavings, a Nunivak Island resident elected to speak for 57 villages at a government General Services hearing on whether or not the military should be hired to replace the BIA’s “North Star” operation.

“‘North Star’ is not only service our villages. ‘North Star’ also faithful and well know people,” he reported. “They know it from all over the coast of Alaska. They have many friends. They support North Star from all our villages.

“When ‘North Star’ just about ready to come into the village, these low income people, they don’t have a bank, no jobs. There’s seal, fish all over. They usually stop from these. They usually wait just in order to work so they can have a little money from longshoring, things like that.

“So, about all of us, we Eskimos, myself, Paul and that man from Barrow, all our villages, and we need ‘North Star’..

“Not only that, you know, this Mr. Moe, he’s well know person from all over. From when I was about 12 years old, now I’m around 40 years old, and we know him. I wish he would trying to be president. I would vote for him and the villages, they would vote for him. All our villages and all that, we support. You understand what I mean?”

Moe, He’s My Friend

It’s the villagers, individually, that concern Moe Cole, and they realize it. In off-season he visits Alaskans whenever he can. He can’t pass a native hospital without stopping to see if he has friends there. He visits BIA schools outside the state and spends considerable time writing the parents of these Alaskan youngsters, assuring the folks back home the children are doing well or telling them of their needs (like ivory to carve.)

The villagers follow Moe’s career with equal concern. Oh, they don’t know much about Cecil W. Cole. A friend of Moe’s from Seattle asked a Barrow man if he knew Cole and the Eskimo shook his head. Then, on second thought, he asked if the Eskimo knew “Moe”.

“Moe, yes!” the native beamed. “He’s my friend.”

“You say Moe’s captain now?” a Koyuk resident queried. “I can remember when he was washing dishes. This is a good thing. But he doesn’t seem much different.”

Moe is passing out more candy these days. Through arrangement with Bernall Candy Company in Seattle he now has 20 to 30 tons of it to deliver each year. Bernall donates it and all Moe has to do is hire a truck and talk some friends into packing boxes to the ship.

The Eskimos, Indians and Aleuts have become a little more affluent, too. Moe often comes back from trips ashore loaded with dried fish and presents. He has a weakness for native foods but the gifts embarrass him.

“I never wanted anything in return,” he protests. “In Wainwright last year they gave me a birthday party with a mountain of presents. A hind quarter of caribou, baskets…. It was wonderful but I just didn’t know what to say.”

We’re proud to have something to give,” one villager explained. “Moe, he was the only person who was really good to my kids when they were growing up.”

And Moe continues to hit the beach with the same enthusiasm he had 35 years ago.

“Better bring a big bag and tell your friends to come,” he instructs a pint-size citizen of Elim who is encountering him for the first time.

“Are you married?” he kids a giggling seven-year-old at Unalakleet. “How’s your wife? You don’t like candy, do you?”

Mrs. Theresa Riley watched Moe’s recent landing on Shaktoolik beach with pleasure, then joined the candy line with her wide-eyed daughter riding in the back of her mother’s parka.

“When I was a little girl at Deering, Moe used to come and throw us candy and oranges. I wanted to thank him,” she said. “And I wanted my daughter to see him. It makes for happy memories.”

Received in New York on October 16, 1972

©1972 Lael Morgan

Lael Morgan is an Alicia Patterson Foundation Award winner on leave from the Tundra Times in Fairbanks, Alaska. This article may be published with credit to Lael Morgan, the Tundra Times and the Alicia Patterson Foundation.