Tyonek, Alaska August 4, 1972

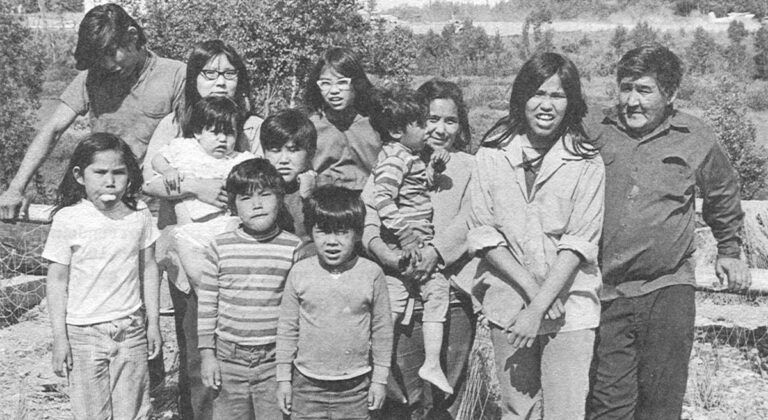

In 1963 the Tyonek Indians, an impoverished, tribe of 200 Athabascans on the shores of Alaska’s Cook Inlet, collected a windfall of $11,671,675. in oil lease revenues.

Despite the fact that few among them had much formal education and their individual incomes had previously averaged at best about $1,000 per annum, the Tyoneks fought vigorously for release from the stewardship of the Bureau of Indian Affairs and the right to manage their own future.

They won, laid a careful foundation for preservation of their prosperity and were soon being hailed by Time, Life Magazine and the Wall Street Journal as the “Tyonek tycoons.”

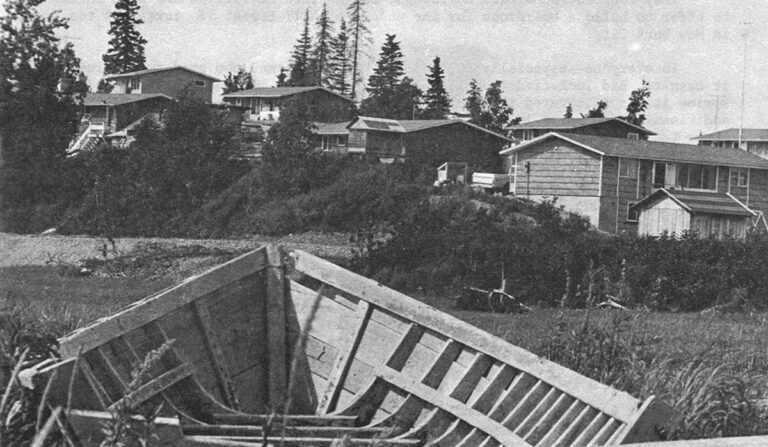

They built a modern village to replace the random sampling of shacks and tattered log cabins they had previously called home. They established an impressive education program for any Tyonek who expressed interest in self-improvement.

They loaned $100,000 to the Alaska Federation of Natives, without which the state’s Indians and Eskimos could probably not have fought for and won their billion dollar federal land claims settlement.

They constructed office buildings, bought into an airline and went so far as to offer to build a boardroom for the wheels of Wall Street if taxes got too tough in New York City.

To everyone – especially the Indians – it all seemed too good to be true, and it wasn’t. Bad luck traditionally plays a major role in Tyonek history and this spring it was discovered their big business venture was no exception. Although additional lease sales in 1967 brought oil revenues of $2,699,056, a recent accounting shows the tribes assets have shrunk from $14.3 million to $8 or $9 million.

An Education

“If they’d invested that money in the bank at just seven percent in long term loans, they’d have $3,100 per year in interest, for every man, woman and child in Tyonek,” speculates Clem Tillion, who represents the area in state legislature. “There’s this feeling you can go out and make the desert bloom but the real profit made in this state today is made like a bank. You don’t let the Office of Economic Opportunity go out and build you a cold storage.”

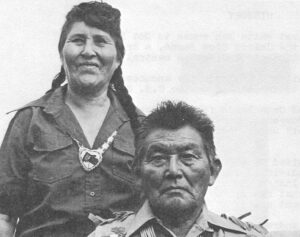

“Right now I kind of wish we had the interest on that money,” admits Seraphim Stephan, who took over as council president last February without realizing how much trouble the tribe was in. “Still it looks a lot better than it did. For the first time we’ve got a 10 year projection and things look a lot better than they were a year ago.”

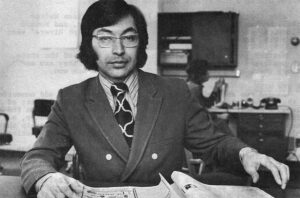

Robert L. Crow, who recently left his job as assistant city manager of Anchorage to unscramble Tyonek finances, agrees the Indians would have done better to leave their investment to the trust department of a good, solid bank.

“But I wouldn’t lay the blame on anyone. Everyone had that new rich feeling. Now everyone has 20/20 hindsight. And, although it is costly experience, it has trained a lot of people. A lot of people on the council really understand what happened and what it’s all about. If they were to manage money again, I think they would do quite well.”

Tribal president.

Off to a Good Start

In 1952 the government limited commercial salmon fishing in Cook Inlet to just two days a week, which pretty much ruined the Tyonek’s chances of making a decent living. They tried coal mining with no success and by 1955 the village seemed so near starvation, the people of Anchorage collected 2,500 pounds of food to get the Indians through the winter.

Then the oil boom hit and the Tyoneks sought advice from an old friend, Stanley McCutcheon, an Anchorage lawyer who had hunted and fished with them as a boy. McCutcheon took their case as a favor, knowing they had no money for a retainer, and, despite scoffing of his colleagues and a lot of legal wrangling, he established the right of the tribe to lease and manage its reservation.

The first lease sale produced $65,000 for every member of the tribe and an unprecedented run of investment counselors, carpetbaggers and encyclopedia salesmen. Cool heads prevailed, however. The Tyoneks closed their airstrip to all but invited guests and placed an ad addressed to salesmen in the Anchorage paper which read: “Don’t call us. We’ll call you. The scalp you save may be your own!”

Francis M. Stevens, a local specialist in community development, was hired as an advisor and a village committee was dispatched with Stevens and McCutcheon to visit other wealthy Indian tribes and study their operations.

As a result, the Tyoneks decided against per capita dole and – even in the light of today’s poor accounting – this is still viewed as a sound decision.

“It’s the best thing we’ve ever done,” maintains Fred Bismark, past council president and one of the Tyoneks to tour reservations outside the state. “I don’t think we’d have had anything left today if we hadn’t gone that route.

“We visited one reservation that was raising cattle. They got into money like we did and all their Indians quit working, waiting for per capita. They’d buy Cadillac cars and if they ran out of gas or broke down they sold them right on the road for practically nothing. Pretty soon they were peddling their cattle and everything. When the per capita stopped, those Indians went back to work.”

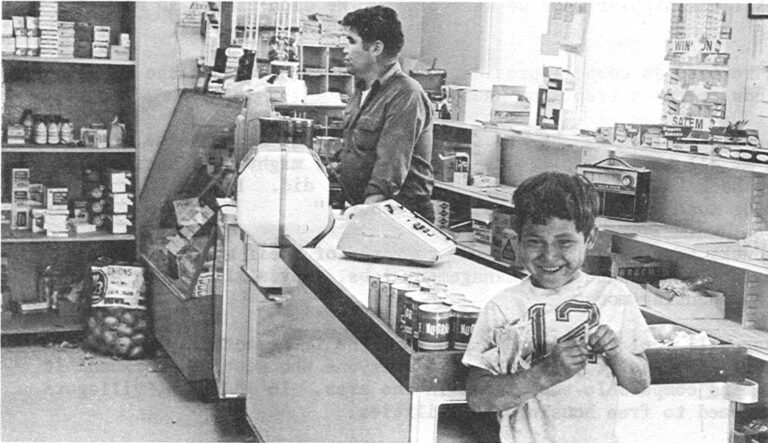

The first thing the Tyoneks did was pay off a $31,434 morgage on their village store. Then they established a 10 point program for rebuilding their community and improving roads and the airstrip.

A family improvement plan, based on the number of family members, provided for building of private housing with a maximum of $40,000 per dwelling. Within two years, 59 new homes were completed in the village along with an eight room guest house at a total cost of $1.5 million. The 50 or so Tyoneks living in Anchorage also got new homes at a cost of $500,000.

A family advisory committee was set up to supervise spending of $5,000 per capita allocations for home furnishings, clothing, household appliances, pick-up trucks and outboard motors. But aside from this program, the distribution of $500 per person in the Christmas season of 1967 and the establishment of a $300,000 trust fund for minors, there were no individual payments.

Villagers were encouraged to undertake schooling and vocational training at the tribe’s expense. They enjoyed free utilities and almost anyone could sign on the village payroll at $3 per hour. But there were no personal bonanzas.

Instead, the tribe put up $250,000 matching for the Bureau of Indian Affairs to build a $1 million grade school. (The new facility had a gymnasium about twice the size of their old one-room school, plus five classrooms, a multipurpose room and hot lunch facilities.) It also invested in a $3.5 million power plant and ornately refurbished the Tyonek Russian Orthodox Church at a cost of $25,000.

The Indians considered outside investment but decided to keep their money in Alaska, favoring those who had been kind to them during hard times. Having secured the home front, they spent $2 million to build two large office buildings in Anchorage (46 air miles northeast) and bought several smaller buildings. They also picked up interests in a title company, a utility company and the three plane airline that had faithfully serviced the village when it was poor.

Bad Luck

In the midst of this prosperity, an eerie run of bad luck occurred. In April of 1966, the very night before they were to move to a new, ranch-style house, a Tyonek family with four children burned to death in their old log cabin. Two months later the president’s father was arrested for shooting another villager and received a five-year suspended sentence. Then, in September, Tyonek council president, Albert Kaloa Jr., was burned to death with 13 others in an Anchorage hotel fire.

“Kaloa was young, smart, with a tremendous amount of common sense,” Stanley McCutcheon remarked at the time. “The Tyoneks probably felt a keener sense of loss than if the death had taken place in their own family.”

Kaloa’s leadership was missed but the real reversal of Tyonek’s fortunes was not apparent until 1970. At first it appeared to be simply more bad luck. The gas well on which the reservation depended for power ran out and a second well lasted only two weeks. The village, which was all electric, was forced to import diesel oil from Anchorage to spin its turbines and costs ran about $600 a day.

In an attempt to recoup the tribe offered a fourth of its reservation for lease in hopes of repeating the 1964 sale, but this time there were no takers. The oil industry was depressed and lands had been explored and found lacking.

By April of 1971, the Tyoneks were having trouble meeting the village payroll and, to make matters worse, the fishing season was unusually poor. But the problem went beyond luck. A casual look at the books showed the tribe had over-invested, leaving too little money for operations and had made many unsound investments.

Number one on the list was Braund Inc., a construction company which Tyonek had backed even when it became apparent the contractor was not bondable. When this venture buckled, the Indians found themselves with a $2.3 million loss.

There was a good chance they could have backed out of the deal but instead they promptly wrote all creditors assuring them that somehow the Tyoneks would honor their debts.

“They could have played it differently,” business manager Crow speculates. “It would have been difficult if not impossible for creditors to take the Tyonek’s homes which were tied up (as collateral), not to mention the fact they were on a federal reservation.

“But they said, by gorry, if they owed a bill, they would pay it. They didn’t want a free ride out. That’s one reason I took this job.”

Crow discovered many other Tyonek investments on the debit side of the ledger.

“The two office buildings they built are all right but they tied up a horrendous amount of capital in them. Paid for them outright when they could have built 10 buildings on the same amount. And the other buildings…even if everyone had paid their rent, they never would have broken even.”

The airline, which is a well-run money maker, pays no dividends, plowing gains back into equipment. The utility company is sound but the stock not readily marketable.

“You might think it’s worth $8 a share but the banker will tell you two,” Crow recalls grimly.

The first move Crow made was to take a close look at the defunct construction company and, through a series of negotiations, suits and counter suits, it appears he may recoup half a million of the $2.3 loss.

Then he found a buyer for the business property that wasn’t producing and arranged for the sale of the electric plant for $455,000 and 11 years worth of free electricity.

Still in need of cash to meet the payroll, the Tyoneks exercised their vote on the utility company to push successfully for a $90,000 dividend and are now pressing for repayment of their $100,000 loan to the Alaska Federation of Natives.

Now Crow is working to consolidate the tribe’s short term loans and mortgages for some long term money.

“We’re working on a package banks will want to compete for,” he says optimistically.

In the early struggle to get on top of their financial dilemma, the Tyoneks were cagey about keeping their problems to themselves. On April 12, 1971, the Wall Street Journal carried a piece titled, “What Will Alaskan Natives Do With Riches? A Wealthy Indian Village Offers an Example.” This was a time when the Tyoneks couldn’t meet the village payroll but the writer never learned of the problem and simply rehashed old Tyonek tycoon stories.

In October the Anchorage Times investigated rumors of Tyonek trouble and came off with an airy statement blaming the problem on the fact oil hadn’t been discovered on the reservation and the gas wells had given out.

Finally, when the Indians had assessed their resources and decided they had a fair chance of recovery, they issued a straightforward news release to that effect.

Ahead of the Game

Villagers understand their financial reverses and accept them calmly.

“We’re not broke, you know. We simply invested too much cash and didn’t keep enough for operations. We’ve still got investment,” reasons Fred Bismark. “Although I think I was happier when we were broke. We didn’t have so many problems then.”

When Bismark retired as council president last winter he taught the oldest of his 11 children how to run a trap line and hunt.

“The boy – 16 – did real well,” he reports proudly. “But he asked me, “Wy are you teaching me all this?’ Well, I told him, “There might come a time when you’ll have to go back to living off the country like I did. I might not be here and you’ve got your mother and sisters to think about.”‘

While the Tyoneks have grown used to the comforts of their modern homes and many have worked into maintenance and management jobs, they still keep a hand in smoking fish and hunting moose.

Of course they will feel considerable pinch if the tribe actually goes broke. The village council has made it policy to hire everyone who wants to work and it would be hard to find comparable employment in the area. In addition, villagers have become accustomed to free housing and utilities.

However, as a result of education and work experience programs, the Tyoneks are far more employable and able to cope with the outside world than they were before the boom.

Neighbors long regarded Tyoneks as proverbial drunken Indians but a few years ago most of the villagers who had been considered hopeless alcoholics voluntarily went on the wagon.

“They did it for different, personal reasons,” says Mrs. Virginia Trenter, health aid. “I guess they just got tired of drinking.”

“If they’ve changed in any way, I guess it’s just that they have more respect for themselves,” observed George Spernak, part owner of the tribe’s airline . “And they have reason to.”

Promising Future

There’s no question but what the Tyoneks will have to tighten their belts but their future looks promising. For one thing, the land claims settlement may have turned out to be one of their soundest investments. Not only will they get back their $100,000 loan, but under the legislation they will increase their holdings from 26,900 to 115,000 acres (by relinquishing reservation status).

If oil is found on this land, the revenues from it will go to their region and the tribe will get only a share.

“But at this point jobs count and there would be work in Tyonek,” Crow points out. “And we’ve got a regional commitment for development of Tyonek mineral resources as first priority.”

While oil companies are dubious about finding oil on the land, the Indians remain optimistic.

President Seraphim Stephan (who can walk out his office door and gaze on oil rigs pumping in Cook Inlet near by) summed up their feelings:

“There’s some land we didn’t feel right about leasing before,” he said, glancing casually over the onion dome of the Russian Orthodox Church and the neat village. “We still think oil’s got to be here somewhere.”

Even if it isn’t, Tyonek is well stocked with fish, game, coal and timber. The tribe is just undertaking issuance of fishing licenses to outsiders (who land 20 to 30 planes at a time on Tyonek beach) in silver salmon season. Camp sites are being built. A timber industry is being encouraged and the tribe is trying to attract outside investors.

“I feel the people are so fish oriented that this may be what they’ll go into,” Crow said. “If there’s going to be a fishery on Cook Inlet, this would be a good place for it.

“A few years ago they never thought in terms of anything less than a Ford Motor plant, but what they have at the most is a work force of 30 or 40 people. If we can put something that employs six people in and build on that….

No Bitterness

In spite of financial woes, the Tyoneks remain remarkably free of bitterness. Many outsiders blame lawyer McCutcheon for the bad investment advice the Tyoneks heeded, but tribal spokesmen don’t discuss the subject with outsiders.

“He’s still our lawyer,” observes Stephan. And as for community planner Stevens, “I don’t know. I think he’s turned to marriage counseling…. But what happened to us could have happened to anyone.”

Tyonek philosophy – perhaps the Indian’s greatest asset – is best summed up in a newsletter published after the death of Kaloa and the series of tragedies that beset the village in 1966. It was just before Christmas and the writer took careful stock:

“We have been blessed with many good things.

We have experienced some misfortunes.

We can be grateful for the nice things that have happened and also grateful we have not experienced more misfortunes than we have.”

That still goes in Tyonek.

Received in New York on August 8, 1972

©1972 Lael Morgan

Lael Morgan is an Alicia Patterson Fund Award winner on leave from the Tundra Times in Fairbanks, Alaska. This article may be published with credit to Lael Morgan, the Tundra Times and the Alicia Patterson Fund.