Photos by Frank Murphy

Fairbanks, Alaska July 15, 1972

One of the most astonishing survival stories of the Far North is that of the Tundra Times. This fall the little Eskimo-Indian newspaper celebrates its 10th year of publication, flourishing in the financial wasteland of the Arctic on an erratic circulation that wavers between 1,500 and 5,000.

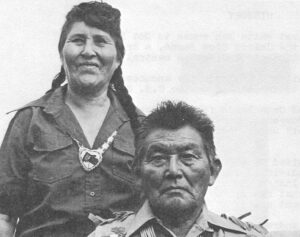

More remarkable is the influence exerted by this hardy weekly and its Eskimo editor, Howard Rock. Working with one reporter, or often just a part-time staffer, Rock has shaken high offices in Washington, D.C., with the force of seismic seizure and helped change the face of Alaska.

Perhaps more than anyone else, he helped weld together the frontier state’s 55,000 natives for their successful, years-long fight to win the largest aboriginal land-claims settlement in American history,” notes Stanton H. Patty, veteran Alaskan observer for the Seattle Times.

“He was their voice, at times about the only calm voice when crescendos of invective threatened to tear Alaska apart.”

If credit is given where credit is due, however, Rock would not be the original hero of this tale. That honor belongs to the Atomic Energy Commission (AEC) to which Alaskans often assign the role of villain.

Peaceful Uses of Atomic Power

In 1958 the AEC developed a plan to excavate a harbor with nuclear explosives in Alaska’s northwest Arctic. The need for a deep water refuge on this storm-strafed coast had long been felt by the handful of seamen who ventured there and proponents of the blast believed it a good chance to test the peaceful uses of atomic power.

They failed, however, to take into account the 800 Eskimos who lived in the area of Cape Thompson, the chosen blast site. The isolated natives knew little about the work of the AEC but they had heard of the Atomic Bomb and they began to worry that their game and perhaps their very existence might be threatened.

“There were attempts to lull us, the people of Noatak, Kivalina and Point Hope,” recounts editor Rock who was born in Point Hope. “We were wheedled with rewards of acclaim from science and the peoples of the world if we would agree to go along with ‘Project Chariot.’

“We, the people of the three villages, did not go for the enticements. We chose to remain in our home villages come what may. The love for our homes, however humble, and the deep sense heritage prevailed…”

To defend this heritage an unprecedented meeting of Eskimo leaders from 20 villages was held in the fall of 1961. It was called “Inupiat Paitot” – The People’s Heritage.

Until this time there had been little communication between native communities and even less between natives and whites. Major Alaskan newspapers seldom carried news of Indians and Eskimos and showed little concern for the problems of native people.

As a result of Inupiat Paitot, it was decided the native people must have a voice of their own – a newspaper. To found it, Eskimo leaders chose Rock, then a well-known artist who was fluent in English but had no writing experience, and Tom Snapp, the only white journalist in the state who had been interested enough to cover the meeting.

Funding for the enterprise was to be investigated by the late LaVerne Madigan, then director of the Association on American Indian Affairs, who helped organize Inupiat Paitot.

At the outset the project seemed impossible. Either it failed to fit foundation specifications or philanthropists required elaborate proposals that would have cost several thousand dollars to prepare.

Finally, in desperation, Miss Madigan volunteered the names of her five richest board members and turned up a winner. Dr. Henry S. Forbes of Milton, Mass., headed the list. He was a retired physician, a descendent of Ralph Waldo Emerson and well ahead of his time in concern for aboriginal rights.

Rock wrote him a formal, rather stilted letter and the answer – long in coming – was a question:

“What do you need a newspaper for and what are the issues?”

Rock left the reply to Snapp who had a ready answer. The reporter had been trying to cover native news for the Fairbanks News Miner but they’d limited him mainly to editing quaint little local-interest columns from the villages.

“It was frustrating. Personal columns! I wanted to cover the issues – education, hunting and fishing rights.

“I did a series on Project Chariot and they (the AEC) tried to stop it. I’d gone through all the Associated Press copy and found the AEC reports didn’t match with what the scientists said. The scientists were upset. They’d found radiation in the food chain and the AEC had tried to cover this up. They were talking in terms of moving mountains and doing mining and they said it was no more dangerous then the luminous dial on a watch!”

After reading Snapp’s 85 page reply, Forbes pledged to back the paper with $35,000 in its first year. His only requirement was that it start at once with Rock as editor and Snapp assisting.

An Unlikely Team

It seemed an unlikely team and Snapp was a reluctant member. He’d come to Fairbanks in 1959 on vacation from the University of Missouri where he was about to start his second year’s work on a Master’s in journalism. He’d already been talked into postponing his schooling once, when the News Miner couldn’t find a replacement for him, and he wasn’t anxious to postpone again.

“His bags were packed and he was even mailing boxes back to Missouri,” Rock still recalls with a shudder. “I was just desperate and I begged him to stay.”

Howard Rock had absolutely no grounding in journalism and he’d been long absent from his native state. Although raised in the traditional Eskimo fashion, he’d left Alaska at an early age to pursue a career in art. He studied under Max Siemes, a Belgian artist, worked his way through three years at the University of Washington and become a successful painter and designer of Jewelry in Seattle.

In 1961 he returned to Point Hope for a vacation and family reunion.

“After the excitement of the whaling season that was climaxed by the whaling celebration, I began to hear some of the problems and fears my folks were having,” he recalls. “One subject that came up most often was the impending nuclear blast. They talked about radioactive fallout, contamination of food animals and probable genetic effects it might have. These subjects were altogether foreign to me. And my ignorance appalled me when the folks said more than once, ‘You came at a most opportune time. It must be the answer to our prayers.'”

Rock set out to educate himself and found Tom Snapp a major source of information. The artist had suggested a native newspaper to his village council but it was Snapp (who turned out to be his roommate at Inupiat Paitot) who really made the idea jell.

Rock didn’t know how or what to write and he didn’t have the vaguest idea how to go about setting up a newspaper. In the end he got Snapp to unpack his suitcases and stay another year.

Parakeet in the Dishwater

“To start a paper is a tremendous job,” observes Snapp who now publishes All Alaska Weekly, the liveliest general issue paper in the state. “Mine took five or six months but the Tundra Times had just two weeks.”

Fortunately Snapp’s sister had gone on vacation leaving him in charge of her trailer. The two men set up shop there, working round-the-clock three days straight, catching a night’s sleep, then working three more straight days and nights.

“One problem was the parakeet,” Snapp recalls with a smile. “I was supposed to take care of it and Howard just couldn’t stand to see it caged up. He used to let it out and it was always flying headfirst into our dishwater.

“Of course we had to eat our meals right there…and the back-shop kept complaining because we had peanut butter and jelly on our copy.”

It was the midst of the political season and Snapp and Rock ran themselves thin collecting political ads.

“We stuck together just like that,” Snapp brandishes crossed fingers. “That’s what we did that whole year almost. That was the deal. He got a journalism education in that year he’d have had to go (to school) two or three years to get.

“We talked about what he knew. He was very proud of his Eskimo culture and he started telling me all these fantastic things like you go to the supermarket now and they have all these plastic bags they wrap everything in. Well, he said, ‘We’ve had that for centuries.’ What it was, was oogruk (giant seal) gut. They cleaned them out and made pokes out of them. And all that frozen food…They’ve been having frozen food like that for centuries.

“I started encouraging him and he started writing about all these things. He wrote for months about Arctic survival and his traditions and it ought to be reprinted. Some fantastic stuff.

“He had a natural bent for writing. It wouldn’t have worked with just an ordinary person. He had an art background and an appreciation for humanity. He also had a rich heritage. He could appreciate both cultures and he believed you could mesh the two.

“Inupiat Oqaqtut” Won’t Go Over The Phone

One of the biggest hassles was finding a name for the publication. At first they picked “Inupiat Oqaqtut”. Eskimo for “The People Speak.”

“But what if we got a non-Eskimo for a secretary?” someone asked. “She would have the darndest time trying to put that over the phone.”

Finally they settled on Tundra Times and flanked it with explanations in Alaska’s four major native languages:

Unanguq Tunuktauq – The Aleuts Speak.

Den Nena Henash – Our Land Speaks (Athabascan).

Ut kah neek – Informing and Reporting (Tlingit).

Inupiat Paitot – People’s Heritage.

The first issue hit the street Oct. 1, 1962, with the banner:

INTERIOR SECRETARY UDALL VISITS ALASKA–HISTORIC RIGHTS AND CLAIMS SETTLEMENT IS NUMBER ONE PROBLEM, DECLARES OFFICIAL.

There was also an editorial explanation of Tundra Times intent.

“Long before today there has been a great need for a newspaper for the northern natives of Alaska. Since civilization has swept into their lives in tide-like earnestness, it has left the Eskimos, Indians and Aleuts in a bewildering state of indecision and insecurity between the seeming need for assimilation and, especially in Eskimo areas, the desire to retain some of the cultural and traditional way of life.”

It promised unbiased presentation of native issues and added the paper would support no political party.

“With this humble beginning we hope, not for any distinction, but to serve with dedication the truthful presentations of native problems, issues and interests.”

Snapp’s former associates at the News Miner took one look and sent word they’d give the paper six weeks.

Files In The Ice Box

The Association on American Indian Affairs wasn’t much more encouraged. When their representative arrived in Fairbanks to inspect the new Tundra Times headquarters, he found its staff struggling to settle a small office on the main street.

“We couldn’t afford file cabinets or anything like that but the place came with an ice box and stove that didn’t work,” Snapp recalls. “We kept our papers in there and when the AAIA man wanted a tour of the plant that’s about all we had to show him.”

They also had more than the usual share of problems to report.

“Starting a native paper at this time was very rough because there was distrust against us,” Rock explains. “It took a lot of nerve, really. We had things thrown through the door at night and I was threatened with beatings and things like that, but somehow we just kept right on going.”

“We got all kinds of trouble along the way,” Snapp adds. “One thing, the utility company asked for a much larger deposit because none of the incorporators had a credit reference. Once when I placed a long distance call that cost more than $100 the operator called back and told us we had to come down and pay the bill at once…in the middle of the night!

“Then there was the cost of printing. Outside I’d paid $3,000 for printing 32 times a year. Here, for 24 issues, they wanted $28,000.

“We were stepping on some awfully big toes.”

The Atomic Energy Commission had called off plans for a major blast at Cape Thompson before the Tundra Times began publication but in April of 1963 it filed a new application for land withdrawal. The Tundra Times bannered the news and the project subsequently died.

The paper also reported findings of scientists on Russian atomic testing. Fallout had settled on the Alaskan tundra and been absorbed by caribou that grazed there. Eskimos who lived exclusively on this game were found to have a higher radiation count than any people in the United States. AEC began to monitor their exposure and the Tundra Times monitored the AEC.

Rock and Snapp also began actively pushing for settlement of native land claims.

“You see the federal Bureau of Land Management had never plotted native claims on their records so people would check and find no claims,” Snapp explains. “All those claims the natives had been filing for years were with the Bureau of Indian Affairs down in Juneau or in the archives in Washington, D.C.”

In 1962 five oil companies filed leases between the native villages of Nenana and Minto and private businessmen followed suit. The state got word of oil activity and started making tentative selection under the federal Statehood Act and no one paid any attention to native claims which had accumulated over the years.

“We didn’t know who you could trust to get an attorney,” Snapp shakes his head. “You couldn’t tell who was your friend. We finally got Ted Stevens (now a U.S. Senator) who said we should file a protest. It would probably be dismissed locally but we could appeal.”

The problem was that the natives had filed a number of conflicting claims on maps too crude for legal use, so Snapp and Rock bought huge, detailed maps and traveled to the villages to straighten out the contradictions.

“As soon as our first native suit was filed, there were two more, even bigger. That’s when the first freeze came against the state,” Snapp reports.

“Then Udall came to the Tundra Times banquet and announced deep freeze,” Rock adds with pride. “The natives had filed suits all over the state.”

The paper also campaigned for abolition of “semi-servitude” for the people of the Pribilof Islands.

“In those days the Bureau of Commercial Fisheries controlled the Pribilofs. It was kind of a company store arrangement, where hunters were paid in kind for their seal skins. They had to barter with the government,” Rock says.

“The Tundra Times did so well on that series the Bureau of Fisheries threatened to expose us as Communists,” Snapp recalls.

Tundra Times reporting was so lively other newspapers in the state became interested in covering native news. Soon a number of white reporters were plugging away on the issues of subsistence hunting rights, education, equal opportunity and a decent standard of living for natives.

Precarious Existence

Tundra Times existence has remained precarious, however. Despite generous financing by Dr. Forbes (until his death in 1968) the overhead has remained high and circulation low.

Reading comes hard to many Alaskan natives and so does the $10 Tundra Times subscription fee, so often one copy of the paper services an entire village. The bulk of the subscribers are native leaders, government agencies, other newspapers and interested whites.

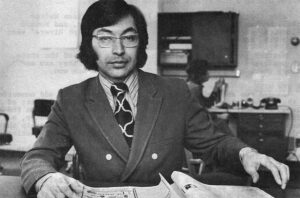

Reporter – Jackie Glascow ponders the issues.

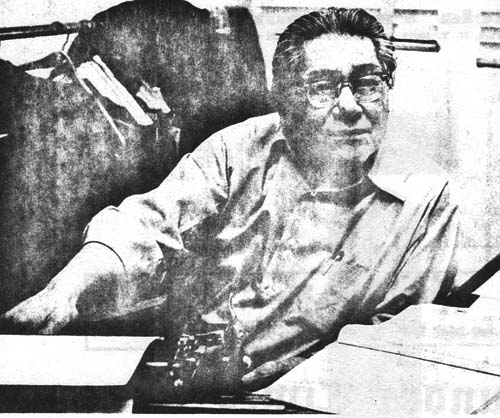

Secretary – Joyce Ard serves the paper as receptionist, bookkeeper, sets all the type and proofreads.

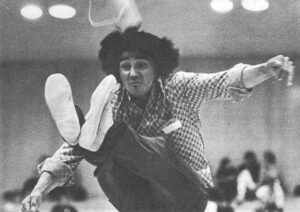

Frank Murphy – Advertising manager also doubles as a photographer, dark room technician and reporter.

His desk and darkroom are in the office coat closet.

In 1966 the paper incorporated as the Eskimo, Indian, Publishing Co., Inc. (with a native controlled board) and many well-wishers began to purchase stock at $25 a share to keep the paper going. Rock has taken on additional fund raising ventures like the Tundra Times annual banquet and management of the Eskimo Olympics, and whenever the wolf is really at the door, something unusual turns up.

The current angel is Rural Alaska Community Action Program which purchases a page to publish its own news twice monthly. The Alaska Federation of Natives sometimes buys subscriptions for native villages. So does the National Guard. And other organizations, both native and white, have provided loans or grants.

When Snapp resigned to go back to school, the little paper could not offer the kind of salary needed to attract a reporter of similar caliber but a good man turned up anyway. When he quit, another materialized out of the blue, and it’s still happening.

During one bare budget siege, an east coast heiress volunteered to work for Rock free and turned out to be a remarkably good writer. She was followed by a top flight magazine editor from New York who worked for expenses one summer.

Currently the job is being held by a former interior decorator who writes like Faulkner, has a good feeling for the issues and lives on bread and water.

In addition, there is Tom Richards, Jr., a Young Eskimo who was drafted following an outstanding apprenticeship with the paper. Rock, now 61, hopes Richards will eventually work into editorship and the young reporter is enthusiastic about the idea.

Settlement Is Just The Beginning

For Howard Rock, settlement of the land claims does not mean the end of a fight but a new charge. After meeting with other native leaders for announcement of the bill’s passage, he wrote, “The (Congressional) vote was overwhelming, to be sure, for President Nixon to sign the measure. There was a 40 million acres of land award in the offing, and there was $962 million – a payment for lands lost. These are almost astronomical figures, but at the end of the voting, they were met with almost dead silence by the 600 native delegates…

“One would think that some measure of elation would be apparent. Instead something else happened. We do not know exactly what.

“The Alaska native people have a profound sense of belonging to their lands, or a profound sense of ownership. The delegates must have sensed that as they voted, they were also voting to relinquish some 300 million acres of land forever-lands they and their ancestors were accustomed to using for their subsistence. Indeed this was what was happening and there were mixed feelings,

“We believe that the measure will be the closest to a substitute to the former way of living. It will not do away with subsistence living altogether. It can be a good basis for perpetuating charming cultures and traditions. It will provide food for the table. In order to make it do these good things, the provisions in it must be handled carefully, always with feelings that it is being done for the good of the present generation and for the good of the native people in the future.”

And that will take some watch-dogging. The 13 regional corporations set up to administer the bill will undoubtedly produce newspapers of their own but Alaska still needs – now more than ever – a strong, statewide native paper.

There should be more money to support one, too. In fact, under the management of Frank Murphy, the Tundra Times advertising revenues have increased considerably even though the claims settlement payment is still two years off. The paper has grown from eight to 12 and 16 pages since last summer.

Eventually Rock hopes to increase village coverage and circulation; add an easy-to-read supplement for those who speak English as a second language; develop a wire service for native news; build his own printing plant and go daily.

The Biggest Whale

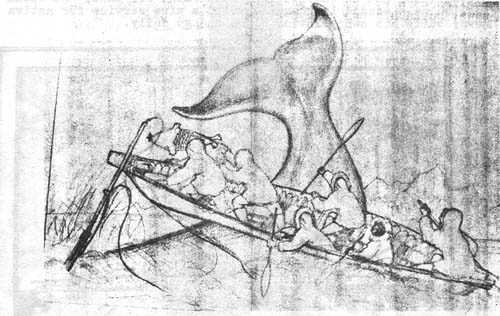

Occasionally Editor Rock gets nostalgic, unearths his old sketch books and moodily thumbs through their yellowing pages. He has not picked up a paint brush since 1961, although the canvases he did at that time are now selling for $1,500 and $2,000.

He has no time for art now except for serving as a member of the Indian Arts and Crafts Board for the Department of Interior.

“I just think that expansion of the paper is more important than my painting,” he says quietly. Then he smiles, recalling his beginnings and his family who have been famous Point Hope whaling captains for generations.

“My brother, Allan, used to tease me. He used to say, ‘You know, Howard, you’re the only man in our family who never got a whale!'”

But perhaps Howard Rock has caught the biggest whale of all.

Received in New York on July 19, 1972.

©1972 Lael Morgan

Lael Morgan is an Alicia Patterson Fund Award winner on leave from the Tundra Times in Fairbanks, Alaska. This article may be published with credit to Lael Morgan, the Tundra Times and the Alicia Patterson Fund.