One of the greatest obstacles to national development throughout sub-Sahara Africa is illiteracy. Low levels of education prevent contact between government and the masses, the transmission of better techniques for agriculture and production, and realization of national goals and priorities.

Upon independence on June 25, Mozambique’s population was 80 percent illiterate. But a radical program to educate the nine million population of this southeast African country is already making a dent in this figure, and at the same time rallying support for the new government.

Robin Wright has been in Mozambique for three months investigating changes made during the transition period. What follows is Wright’s assessment of the Alphabetization program and its impact on the people — and future — of Mozambique.

Lourenco Marques, Mozambique

The teacher authoritatively pointed to letters on the worn blackboard with the end of an equally worn broom. In unison the students obediently repeated the sequence of one syllable words using the letter a. then the letter p.

“Yes,” he said approvingly in Portuguese. “That’s good, let’s try it again.” And the group of 32 pupils once more followed his instructions. After all, he was the instructor.

It might have been an ordinary classroom scene — except that the teacher was an 11-year-old boy, the students all adults, including his mother, and the class part of a government-sponsored evening education class.

For all its unusual characteristics, it is not an unusual scene in Mozambique these days. The session is typical of the new classes organized under the “Alphabetization” program throughout this southeast African country in recent months. It is one of two key programs pushed by the new government since Frelimo (Front for the Liberation of Mozambique) moved into Mozambique, first as part of the transition government in September, 1974, and later taking full control at independence on June 25 this year.

Alphabetization is a revolutionary, fast-action program designed to educate the 80 percent illiterate population with the help of volunteer instructors, mostly students themselves. Anyone having passed a certain level can teach the level he has passed. The 11-year-old, for example, had passed standard one and was allowed to teach the basics he had recently learned.

Alphabetization is a revolutionary, fast-action program designed to educate the 80 percent illiterate population with the help of volunteer instructors, mostly students themselves. Anyone having passed a certain level can teach the level he has passed. The 11-year-old, for example, had passed standard one and was allowed to teach the basics he had recently learned.

The classes, however, reveal more than just Frelimo’s concern with education. They also reflect the degree of planning by the party during the ten-year “liberation war” between Frelimo guerrillas and Portuguese troops.

As Frelimo founder Eduardo Mondlane wrote in 1968: “One of the chief lessons to be drawn from nearly four years of war in Mozambique is that liberation does not consist merely of driving out the Portuguese authority, but also of constructing a new country; and that this construction must be undertaken even while the colonial state is in the process of being destroyed.”

“Exposure to the problems in other countries is one of the few benefits of gaining independence after other countries,” another Frelimo official remarked recently. “We had time to organize and learn from others’ mistakes.” As examples, he pointed to Somalia and Nigeria, where similar mass education programs are just getting underway, over a decade after independence.

As a result of its early concern about social welfare programs, Frelimo set up alphabetization classes as far back as the mid-60s in the northern provinces its guerrilla forces had “liberated” from Portuguese control. Few dispute its claims of teaching over 20,000 during the ten-year war, more Africans than were taught by the Portuguese in the 90 percent of the country still under colonial rule.

Although the Portuguese offered “multi-racial” education, few blacks could enroll because of the prohibitive cost of books and the need to start children in jobs at an early age to supplement low family incomes. Only about two percent of the black population was in school, and mainly in the mission schools where supplies were provided. In comparison, approximately 95 percent of the Portuguese children were in state and private schools. As one diplomat suggested, “The state looked after the whites, and the churches looked after the blacks — as many as they could anyway.”

Almost overnight there was a reversal of this trend because of Frelimo’s belief that education is the key to national development as well as the chief means of politicizing the masses to its socialist ideology. The movement is clearly giving education a political base. Beginning with standard one, the tools used are all related to the party.

The texts — usually well-worn mimeographed sheets — are all based on Frelimo: writings of the leaders, the party platform, and key dates of the liberation struggle. Even arithmetic is based on story problems about the low prices paid by the Portuguese for Mozambican goods during the colonial era compared with the real market value the country can now realize.

The texts — usually well-worn mimeographed sheets — are all based on Frelimo: writings of the leaders, the party platform, and key dates of the liberation struggle. Even arithmetic is based on story problems about the low prices paid by the Portuguese for Mozambican goods during the colonial era compared with the real market value the country can now realize.

Members of one standard four class, for example, were assigned to write essays on how to fight famine, a problem in northern Mozambique.

A nine-year-old boy wrote in simple but heartfelt words about the importance of developing agriculture through hard work on the new collective farms being set up by Frelimo throughout the country. A 30-year-old woman, baby strapped to her back, shyly read her essay on the importance of “comrade helping comrade” beyond color and tribal lines — one of the familiar phrases of the Mozambique revolution — to eliminate problems like hunger. The short speech drew applause from her classmates.

Although figures on attendance in these classes are unavailable, the turnout is impressive. There are 400 pupils attending the evening classes in one Lourenco Marques school, unused by blacks a year ago. Schools and local party offices are often busy with alphabetization classes from 7 p.m. until midnight. Anywhere from 30 to 60 fit into the small rooms, many having to sit on the floor because the wooden benches are jammed. One kindergarten room, equipped with miniature furniture for the tots who attend the daytime sessions, is burdened with full-sized adults cramped onto the tiny seats.

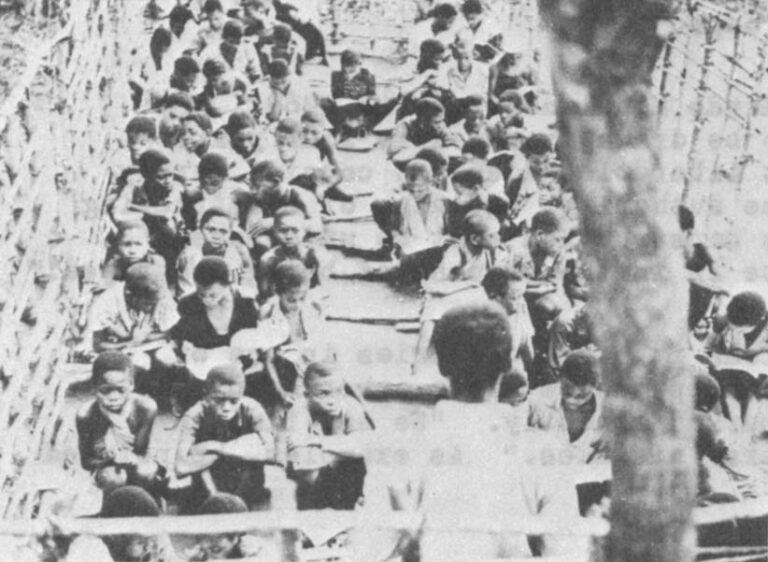

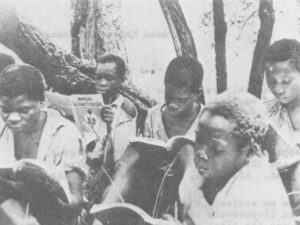

In the vast rural areas, classes are held under trees, in open fields and in thatched huts, drawing people living many miles away. Materials are scarce in these provinces, where teachers often draw diagrams in the dirt or write with charcoal on bark trimmed off a nearby tree. It is a luxury when students can write on a blackboard with dry cassava as chalk. Instead of paper or slates, pupils often use a piece of wood, which they scrape with a knife to erase what they have written.

In the vast rural areas, classes are held under trees, in open fields and in thatched huts, drawing people living many miles away. Materials are scarce in these provinces, where teachers often draw diagrams in the dirt or write with charcoal on bark trimmed off a nearby tree. It is a luxury when students can write on a blackboard with dry cassava as chalk. Instead of paper or slates, pupils often use a piece of wood, which they scrape with a knife to erase what they have written.

Alphabetization so far appears to be eliciting an even greater response than the “dynamization” program. Frelimo’s second key program for the masses. Dynamization is the political awareness effort to organize cells as the basis for local government. “People identify more readily with the education program,” one foreign observer explained. “Dynamization and politics are still too abstract for many of them. They don’t see the results since power is a new concept to them. But schooling isn’t. They can participate in classroom situations instantly.”

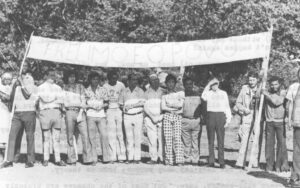

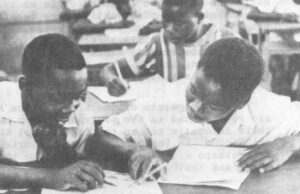

Most segments of the nine million Mozambique population are represented in the program. Black nationalist soldiers, their automatic rifles resting against their desks, houseboys still clad in the standard white shorts and shirt uniform, and mothers with sleeping children in their laps all share desks and textbooks.

Most segments of the nine million Mozambique population are represented in the program. Black nationalist soldiers, their automatic rifles resting against their desks, houseboys still clad in the standard white shorts and shirt uniform, and mothers with sleeping children in their laps all share desks and textbooks.

Even teachers become students, allowing pupils to take over the class periodically. “I don’t know better than my comrades,” one 17-year-old instructor explained in faulty English. “I learn from them, especially about politics and the people’s needs.”

At several points he retired to a wooden bench while, for example, a middle-aged woman stood before the class and talked about the history of the liberation movement, or a teenage girl discussed the problems of her people. There is a community spirit in the classrooms, where pupils and teachers address each other as “comarada,” the Portuguese word for comrade or friend.

The classroom scenes are not just limited to blacks. Many whites are participating in the alphabetization effort, “a fact that bodes well for the future,” one Frelimo official offered. Most are teachers, although some also attend as students in the higher levels.”

One white teacher — without any formal credentials — explained that she teaches three nights a week “because this is the only way we are going to get Mozambique on its feet.”

“It is the area where there is the greatest contact between blacks and wilites,” one white remarked. “Alphabetization, because of the contact as much as the education, is the hope of this country, if it is to work as a multi-racial society.”

There are plans now to expand the program to encompass vocational training, mainly in agriculture and cattle-breeding. Already advanced levels are learning new techniques for construction of wells, housing and sanitation facilities.

The Alphabetization effort clearly goes far beyond the implications of its title. It is the key to literacy, political awareness and human relations in Mozambique. If Alphabetization can reach the masses, Frelimo will have not only boosted education, but it also will have further tightened its control over national development.

Received in New York July 7, 1975

©1975 Robin Wright

Robin Wright is an Alicia Patterson Foundation award winner on leave from The Christian Science Monitor. This article may be published with credit to Robin Wright, The Christian Science Monitor, and the Alicia Patterson Foundation.