Within the volatile southern African subcontinent — where war, racial tension and political and economic problems compete for headlines — there is only one country comparatively problem-free. A non-racial, potentially wealthy and politically stable nation, Botswana is the only state that is prospering without pressure or without tension in this troubled territory.

Yet, for all its success, the former British protectorate is also the most unheralded country in southern Africa. And, considering that this massive territory was recently judged the most democratic state in Africa, it may rank as the most unheralded country on the continent.

Robin Wright recently visited Botswana and offers the following assessment of The Exception to the trend of events in the southern subcontinent.

Gaberone, Botswana

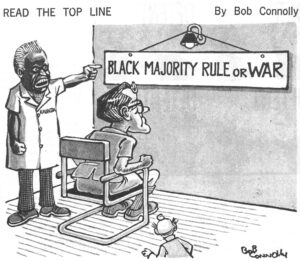

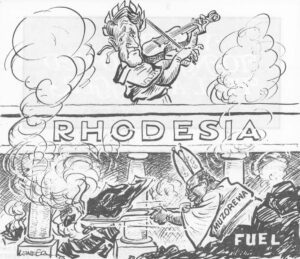

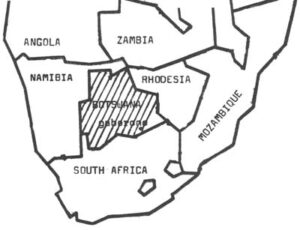

The southern African subcontinent is currently plagued with problems: South Africa’s racial tension. Rhodesia’s decade-old constitutional crisis. Angola’s bitter civil war. Mozambique and Zambia’s severe economic struggles. And Namibia’s campaign for independence.

Yet within this volatile territory there is one country without racial problems or political traumas, where the economic potential has led to a new power base, and where both eastern and western countries are active in peaceful projects. In fact, this country was just judged the most democratic territory in all of Africa by New York’s Freedom House.

But the only reason most people have heard of Botswana is that Elizabeth Taylor and Richard Burton were recently remarried there.

A country larger than France, Botswana is largely ignored by the world press. Perhaps it is because good news is too often no news — and Botswana is definitely good news.

Bordered by South Africa, Rhodesia and Namibia, the former British protectorate may not be the most scenic country. Its sandy rolling terrain which one writer described as “the perfect 180 degree skyline” — and red dirt road-substitutes do not draw many tourists. But in all other spheres — political, economic, and social — Botswana is distinguished for its progressive policies.

Just eleven miles from the South African border, in the mini-capital of Gaborone, blacks, whites, coloreds and Asians share tables in cafes, mix freely in private homes, sit next to each other in cinemas and swim in the same public pools. There are no separate stairways or elevators, no segregated hotels and restaurants, nor divided toilets and transportation systems for the different races, as there are in South Africa. No African calls a white “boss” or “madame” and no European assumes his superiority to all blacks.

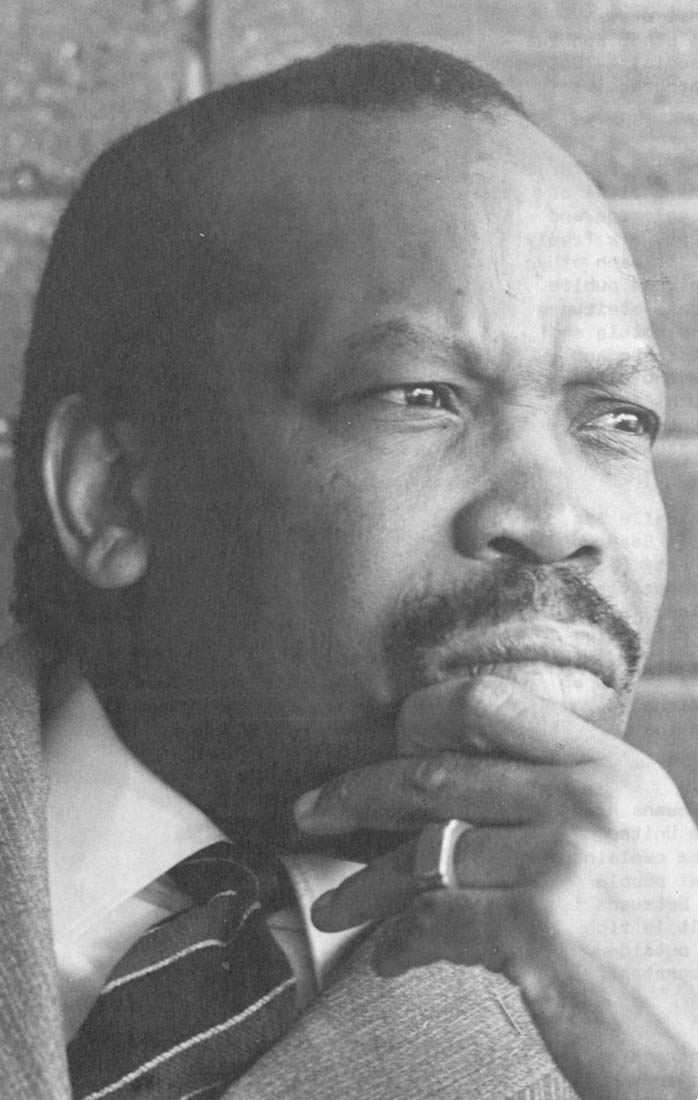

It is also a democratically run country, where President Sir Seretse Khama and his Democratic Party faced not just one, but three, opposition parties in the 1974 election. All were provided time on the national radio and space in the country’s main newspaper. This makes it one of less then half a dozen nations in Africa where there is more than a single, dominating party.

And economically, Botswana has been — as a member of the United Nations Development Program explained — “discovered. Although most people never heard of the place, Botswana is on all investors’ maps. It is rich in minerals, wide open to outside help and, probably most important, stable.”

As a result of its increasing stature, the country has become increasingly important in the southern Africa political drama, especially the current detente exercise. Sir Seretse Khama was invited by the powerful presidents of Mozambique, Tanzania and Zambia to join in their effort to help Rhodesia’s black nationalists find a solution to that country’s constitutional crisis. Botswana is a haven for refugees from all the surrounding states. And several observers feel President Khama may play a vital role in the debate on neighboring Namibia.

Despite his position in the middle of the race-tense subcontinent, the charismatic chief of state, who is also chief of the country’s largest tribe, has taken a hard line on race relations: “There is clearly no future for white minority governments in Africa. The present white minority governments will sooner or later have to give way to more democratic ways of government. The only question is how the transformation will come about. I am still hopeful that the worst can be avoided. But I am afraid time is running out.”

On South Africa specifically, President Khama is also uncompromising: Botswana continues to disapprove of its neighbor’s racial policies and as long as they continue “we cannot consider having diplomatic relations in Pretoria. This is totally out of the question.”

Yet the pragmatic government is not ready to threaten military force to alter the situation in any of its neighboring countries. Botswana does not even “waste” funds on an army. “It is not worth face value,” one government official explained. “Even if we spent our entire national budget on defense we could not muster a force that would really threaten those we oppose.”

Instead, as President Khama has said repeatedly in recent months, “Our most important role in Africa is merely to survive, as an example, to show that a free, non-racial and stable democracy can prosper.”

“Our most important role in Africa is merely to survive, as an example, to show that a free, non-racial and stable democracy can prosper.”

But the government cannot “afford” to threaten South Africa for other reasons. Botswana’s currency is the South African rand (although the country is scheduled to introduce its own notes this year). It imports and exports mainly with South Africa; also, it ships exports to other countries mainly through South Africa since it is a landlocked nation. All communications with the outside world are maintained through South Africa and South African businesses are currently the prime investors and developers of Botswana’s vast new mineral wealth. In addition, about half of the officially employed population works as laborers in South African mines.

But Pretoria is quite content with the Khama government. Botswana now serves as a good buffer zone between South Africa and the rest of black Africa with South Africa pulling enough strings in Botswana to have leverage, if needed. “In fact,” commented one diplomatic source in Gaborone, the (South African) government would like to see Namibia go the way of Botswana rather than fall to radical elements.”

In other words, despite the difference in policies, South Africa will continue to help Botswana “survive” — as will an increasing number of countries from both east and west.

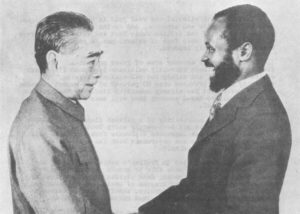

The Americans, Dutch, Canadian and British are all playing active roles in directing and backing schemes from road construction to resource exploration and exploitation. But of greater interest, especially to Botswana’s conservative neighbors, is the new presence of an eleven-member delegation from the People’s Republic of China, which arrived in mid-1975.

Western observers believe China is about to launch a major development plan, along the lines of its schemes in Tanzania and Zambia. The Soviet Union, Rumania, Yugoslavia, Czechoslovakia and North Korea also have diplomatic relations with Botswana, although missions are shared and based in Zambia. The increasing Chinese presence has led several diplomats to speculate that the Soviet Union may soon establish a permanent mission in Gaborone and also provide new financial support.

Much of the new interest is economic, the result of new resource discoveries during the past eight years. Recent mineral finds, most notably diamonds and copper, have transformed the society from a poor agricultural bass to a potentially wealthy mixed economy.

Botswana is not new to mining since the northern Francistown area was the original center of the gold mining industry of southern Africa. But now mining is a booming industry. Apart from well-documented reserves of diamonds (including the world’s second largest diamond pipe), copper, nickel, and coal, there are also significant deposits of manganese, talc, semi-precious stones, asbestos, limestone, elemental salts and marble. Although exploitation is just beginning, meat has already been displaced as Botswana’s chief export (the Lobatse Meat Commission is said to be the largest meat export company in Africa) by minerals.

But there is also increasing strategic and political interest in Botswana, which lies in the cockpit of southern Africa. The desert state shares long borders with Rhodesia and Namibia and, although the government has repeatedly stressed its non-militancy, diplomatic sources feel Botswana would close its eyes to any freedom fighters operating from northeastern or western bases. It also shares a long and vital border with South Africa.

But independent now for only a decade, Botswana is currently more interested in its own problems than those of its neighbors.

All development projects are just beginning and the funds and officials are mainly from outside, since there are few educated or trained personnel available within the country. Until recently children had to be sent to Rhodesia or South Africa for secondary education.

The shortage of water makes use of the arid western area impossible. Botswana is still dependent on South Africa and Rhodesia (the United Nations has granted the country a reprieve from sanctions on Rhodesia) for food and Rhodesia for running the single railway line through the eastern area. Although it is capable of achieving greater economic independence, foreign observers predict Botswana will never be completely free of ties with its neighbors.

But even the problems reflect the hopeful — and unusual — position of Botswana in the troubled African south, for most of them can be eased or solved with time and attention.

As a British diplomat commented: “After assignments in several African countries, I can honestly say this is the most pleasing place I have ever worked. It’s not fast moving or exciting, but after the real problems pulling apart other countries, Botswana is a dream — peaceful, progressive and promising. There’s little to hold this country back.”

©1976 Robin Wright

Robin Wright is an Alicia Patterson Foundation award winner on leave from The Christian Science Monitor. This article may be published with credit to Robin Wright, The Christian Science Monitor, and the Alicia Patterson Foundation.