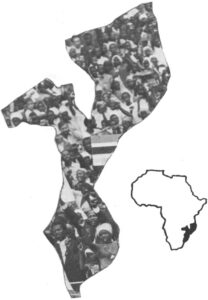

The waiting and speculation is over. The southeast African nation of Mozambique, under colonial rule almost 500 years, became independent on June 25. The new government is now able to act on its platforms and promises.

During its 13 years of political development and the nine months of transition, Frelimo (Front for the Liberation of Mozambique) came out with some bold talk that frightened its “white” neighboring nations. Rumors were rampant in the pre-independence period about the actions the party would take to change the political picture in southern Africa.

But theory does not always become reality, not immediately anyway, as Robin Wright points out in the following assessment of policies in the newly-declared People’s Republic of Mozambique. Wright spent almost four months in the former Portuguese colony, talked with all the key leaders and stayed after Independence to assess the celebration rhetoric.

Lourenco Marques, Mozambique

The statues to Portuguese heroes have been torn down and carted to a city junkyard. The complicated new red-green-yellow-black-white flag now flies proudly from new poles on every corner throughout the capitol. Most streets and cities have been renamed for Mozambican figures or reverted back to their original tribal titles. And black soldiers carrying Russian rifles have replaced Portuguese soldiers with western arms in city barracks and on the streets.

The statues to Portuguese heroes have been torn down and carted to a city junkyard. The complicated new red-green-yellow-black-white flag now flies proudly from new poles on every corner throughout the capitol. Most streets and cities have been renamed for Mozambican figures or reverted back to their original tribal titles. And black soldiers carrying Russian rifles have replaced Portuguese soldiers with western arms in city barracks and on the streets.

The message is clear. After nearly 500 years under Portuguese rule, the southeast African nation of Mozambique is making a clean break from its colonial past.

But the message — as delivered by new President Samora Machel on several occasions since the June 25 independence celebration is not the ruling medium in the newly-declared People’s Republic of Mozambique. For, despite the firmly Marxist tones of most government declarations, Africa’s old independent state is far more pragmatic than its leaders’ rhetoric might indicate.

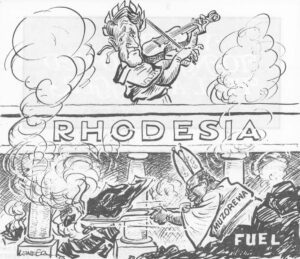

On all the major questions, officials of the new Frelimo government have not yet answered with the radical solutions expected by neighboring nations and foreign observers. These include: application of sanctions against Rhodesia; pressure on South Africa to alter its apartheid laws; development of natural resources; stabilizing a shaky and debt-ridden economy; and establishing badly needed social services for its nine million population.

The reason: Frelimo recognizes that economic realities may have to take priority over political options — at least for the short term.

In debt for approximately $950 million and without any substantial foreign reserves to buy vital imports, the new government must rely on outsiders to explore and exploit the rich mineral deposits in the north and provide capital and equipment for agricultural development. Through expanded agricultural production and new mineral exploitation Mozambique hopes to offer new exports to help straighten out the messy financial situation it inherited from the Portuguese.

In other words, the need for money may be more important than the absolute implementation of Marx right now.

This is most clearly indicated in Mozambique’s tolerance and continued relations with the white minority regimes of its two neighbors — South Africa and Rhodesia. Although the consulates of both countries were closed by June 23, business relations continued after independence through small trade delegations.

It has also been reported that Mozambique will send an unprecedented number of mineworkers to South Africa this Fall. And earlier this year, when minor cases of labor unrest were reported among Mozambican mineworkers in South Africa, Frelimo officials quickly intervened. The South African employer involved commented later: “Obviously they didn’t want things to go to pot. They have a pragmatic approach.”

South Africans do not now even need visas to visit their socialist neighbors, probably so that Lourenco Marques’ $6 million annual tourist trade will not decline any further. Air Rhodesia and South African Airways continue their frequent flights into Beira and Lourenco Marques. And, perhaps of more importance to the ordinary South African, the giant Mozambique prawns are still shipped to South African restaurants.

The stiff measures against South Africa and Rhodesia called for by a convention of the Organization of African Unity in April — for which President Machel was a key lobbyist — led many to believe Mozambique at independence would shut its doors to any business with Rhodesia and cut back as far as possible with South Africa. But so far, Mozambique has moved slowly — if at all. Steps are certain to be taken against Rhodesia if constitutional talks break down, but observers feel little will be done to change relations significantly with South Africa for several years.

Instead, business with South Africa may actually increase, as the mineworker’s situation indicates — again at least for the short term. One South African businessman, for example, approached a leading member of the transition government about a project involving South African capital, technology and supervisory personnel and was given the green light. He later said he expected each approach would be considered according to its merits — not necessarily its backers. American and Japanese firms have also traveled to Lourenco Marques to discuss plans with Frelimo officials.

In the past, about 45 percent of the Mozambique GNP came from services — involving mineworkers, transport facilities and hydro-electric power — to the white South. This cooperative spirit may continue, if one part of the new national budget is any indication. The chief expenditure is to be approximately $165 million for ports and railway improvements, which means mainly the links with South Africa and Rhodesia. Although, some money may also be spent for strengthened transport ties with Zambia, Malawi and southern Zaire.

And giant Cabora Bassa in northern Mozambique, the world’s fourth largest hydro-electric dam, will be turned on as scheduled in October, giving 90 percent of its power to South Africa’s northern Transvaal region. Even during the ten-year guerrilla war against Portuguese troops, Frelimo never made any effort to sabotage the project, despite the fact it “controlled” the area as part of the “liberated” zone. Also, since Frelimo does not have the trained personnel necessary to operate the dam, it is recruiting foreigners from countries not considered its closest allies, including France and West Germany.

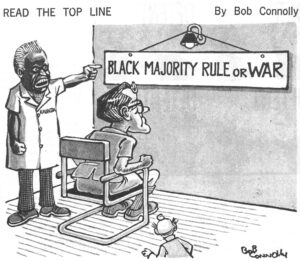

The acceptance of economic realities over political options, however, does not by any means indicate that Mozambique will not act against Rhodesia. As President Machel, has said, “The struggle in Zimbabwe” — the African name for Rhodesia — “is our struggle.”

Since no action was taken immediately at independence, observers expect Mozambique to use its ports and railways — through which Rhodesia ships 80 percent of’ its exports — as leverage against the Ian Smith government. In other words, Frelimo may threaten to close its transport facilities to force the white regime to compromise with black nationalists.

Again Frelimo’s pragmatism shows through. The cutback would mean a loss of at least $50 million in revenues and, perhaps more importantly, the idling of a sizable labor force. Since the United Nations and British Commonwealth countries have pledged financial compensation, the delay in action may also be attributable to the fact that Frelimo needs time to find ways to channel these workers into new jobs and prevent the irritation that could develop into political opposition.

That the economic issues will temper Frelimo’s firmly Marxist political line has actually been clear from the beginning. President Machel may have pleased his socialist allies on Independence Day by angrily declaring that “exploitation is an evil and noxious tree which we have not yet uprooted,” forcing the new government to “launch an ideological offensive to wipe out the colonial and capitalist mentality.” But the small print interspersed in the rhetoric was not as adamant.

Acknowledging that the “economic and financial situation is catastrophic,” Machel said that its solution required “a cool-headed analysis, sector by sector…. We are not hysterical revolutionaries. The 10year war tempered us.”

Specifically, Mozambique will continue to recognize private property, as long as it is developed in the interests of the state. And new foreign investment will be “encouraged” within “guidelines” laid down by Frelimo. Although agricultural land and natural resources technically now belong to the state, the only areas so far nationalized by the government are the farms abandoned by fleeing Portuguese. And there has been no mention of massive nationalization of industry and observers now expect only certain key operations — such as cashew and sugar processing plants — will be taken over soon, and probably with compensation.

Such pragmatism shows Frelimo’s realism and flexibility. But it is also important to note that pragmatism may only be the policy for the short term — ten, maybe 15 years — until the country can stand on its own two feet financially.

Mozambique has enormous potential and once tapped political priorities may take precedence. The People’s Republic is much better off, for example, than its poor neighbor and closest political friend, Tanzania, which is in desperate trouble because of the lack of resources.

Specifically, Mozambique has great possibilities in mining. Although geologists have long suspected that there were rich mineral deposits, the Portuguese never explored the possibilities. Government, diplomatic and scientific sources all now agree that “the Mozambique treasure trove is ready to be unlocked,” as one geologist put it.

Among the known minerals: coal, marble, graphite, bauxite, gold and iron ore have been found in the North. For years gems, including “some of the finest tourmalines in the world” were purchased from northern mines by European buyers who kept quiet about the source. And government sources say there is evidence that the rich Katanga-Zambia copper belt stretches into the northwest province of Tete.

There is both alluvial and reef gold in central Mozambique, as well as masonite and asbestos. And in the south there are proved reserves of one trillion cubic feet and estimated reserves of three trillion cubic feet of natural gas, a resource Mozambique currently imports.

Agriculture is another area of great potential. A very fertile land, farmers currently cultivate less than 17 percent of the territory, and mainly for subsistence farming. Yet this tiny sector provides some 80 percent of the export revenues. The new government has already committed itself to the creation of an agriculture-based economy that will make full use of the nation’s potential.

But even the possibility of a solvent financial situation in Mozambique should not necessarily worry South Africans. The “Frelimo machine” has impressed even diplomats from countries still not recognized by the new government with its cautious and “well thought out policies.”

One observer pointed to Frelimo’s activities during the transition. Officials were able to smooth life into an even keel, despite floods, famine, dock strikes, riots inspired by white racists known as the Dragons of Death, the-much-rumored threat of white mercenary invasion, massive foreign currency smuggling and the exodus of trained Portuguese personnel.

“This is something South Africa should welcome,” a western diplomat observed, “not fear. These are rational, thoughtful people, whatever their politics. They are not like the leaders in Angola — or even Portugal. They are not hotheads.”

“As Machel pointed out, they are not ‘hysterical revolutionaries.’ They have been reasonable in their dealings with Rhodesia and they probably will be with South Africa in the future, even when they pressure for change.”

Received in New York on July 21, 1975

©1975 Robin Wright

Robin Wright is an Alicia Patterson Foundation award winner on leave from The Christian Science Monitor. This article may be published with credit to Robin Wright, The Christian Science Monitor, and the Alicia Patterson Foundation.