With his recent election as the new president of Rhodesia’s black nationalist movement, Joshua Nkomo finally gained the position for which he has long worked. Although an active nationalist for 20 years, the stout and personable leader previously held minimal power because of competition from three rival liberation movements.

But the four factions merged under the African National Council (ANC) umbrella last December with Bishop Abel Muzorewa as chief spokesman. The Sept. 28 election replaced the Bishop with Mr. Nkomo.

A closer look at Mr. Nkomo’s background and political views may offer some insight on the future course of events, now that Rhodesia’s black and white populations are confronting each other over the issue of black majority rule.

Robin Wright interviewed the ANC president on several occasions during a month-long tour of Rhodesia. The following report provides some perspective on the man who may be Zimbabwe’s — the African name for Rhodesia — first black Prime Minister.

Highfield, Rhodesia

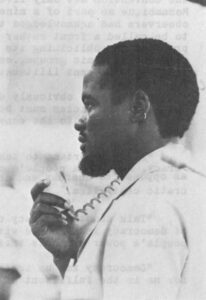

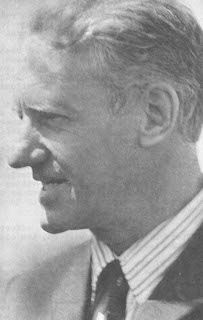

Joshua Nkomo is what one politely calls “big.” Big in politics, but equally big in figure. Both aspects of his “size” were clearly evident when Rhodesia’s newly-elected black nationalist leader welcomed two foreign reporters into his quarters at a friend’s home in the African township of Highfield, just outside Salisbury.

All but eclipsing the large double bed on which he was stretched, the large, lumbering figure was surrounded by several loyal supporters crowded onto the few chairs and tables in the small room. Each listened in total silence to what their leader said as he greeted the journalists.

“Come in, come in, find a seat if you can. Yes, there, that’s good. Where did you say you were from? Oh yes, I’ve been to your offices. Nice people. What would you like to know? Ask me anything,” he offered amiably with a big smile.

Joshua Nkomo was clearly in control of his audience and enjoying it. After 20 years as an active nationalist — for which he is recognized as the “father” of the black power movement — Nkomo has finally won the position that enables him to negotiate — by either words or weapons — with Rhodesia’s white government on behalf of the country’s 5-8.million blacks. On Sept. 28 he was elected president of the African National Council (ANC).

Initially a cautious, almost timid figure in the movement, he has blossomed in recent years and now his charisma and fiery oratory draws more spectators than any other black Rhodesian leader.

His spirited and easy manner reveals this new confidence. Pulling himself up to sit on the edge of the bed,, he began to answer questions.

Would there be any difference in strategy or terms now that his men control the ANC?

“Nkomo’s men? What are these animals called Nkomo’s men? There are no such animals. There are only ANC men,” he answered around the question, stern but still smiling.

Under what terms could he reach a peaceful settlement with the white government of Prime Minister Ian Smith?

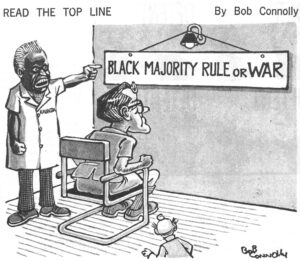

“If you hold a lizard in your hand, he will scratch to get out. If Smith holds us back from what every man deserves, we will resist the oppressor by all means available. Even a lizard wants to be free.”

How far is Nkomo willing to go to get “freedom?”

“If he (Smith) wants to use force to prevent majority rule, then there will be guns to face his guns,” Nkomo shook his animated hands to emphasize the point.

“But you must remember, the Pretoria Agreement (the accord arranging negotiations) calls for a settlement that is acceptable to all the people of Zimbabwe (the African name for Rhodesia). We all agreed on that point at Victoria Falls.”

“I am very much interested in seeing that there is peace. But I am also very much interested in seeing that the people get their rights.”

Considering the opposite positions of the Rhodesian government and the ANC, is there any way to avoid war?

“Smith has got to accept the inevitable. If the white electorate is seriously interested in staying in Zimbabwe, they must allow us to exercise our rights. If they don’t then guerrilla warfare is inevitable. It is a fact that more will sacrifice for their freedom. Our people will give the highest sacrifice to get what is theirs.”

“Smith can’t stop the march forward to independence. We want independence now. If he continues to stand in the way of the people’s progress toward self-determination, then he is wooing disaster. History shows this to be true.”

The new ANC president avoids specifics on any question about settlement terms. An aide explained that this “is understandable.”

He must appear to be open — within certain limits. We do want peace, all of us. And if there is any way to avoid war we will.

“That’s the difference between Nkomo and Sithole (leader of the ANC’s more militant wing). Sithole doesn’t even want to try. He wants to go in now with guns. But that won’t do anyone any good. We must try the peaceful way first.”

The folksy leader has worked long and hard to get to his new position, for which he has had to fight both black and white opposition. Some of his early caution is still evident. “He doesn’t want to jeopardize his job with inflamatory statements, the kind of thing that has provoked Zambia to take action against (former ANC president Bishop Abel) Muzorewa and Sithole,” a Nkomo supporter offered.

“Look at his record. It’s longer than any of the others. How can anyone charge that he wants less than majority rule? He’s not going to make a deal just to assure his own position. Wait and see.”

Nkomo’s record is indeed longer than any other black nationalist leader’s. The 58-year-old former trade unionist, welfare worker and lay preacher took his first steps as a politician in the mid-1950’s with the old African National Congress (not to be confused with the current Council) until it was banned in 1959. To avoid imprisonment he then set up headquarters in London to direct external affairs for the new National Democratic Party, successor to the ANC. Then the NDP was banned in 1961.

At that point Nkomo organized yet another party, the Zimbabwe African People’s Union (ZAPU), which has held together — officially and unofficially — since its formation. During the early years with ZAPU, Nkomo concentrated on getting the United Nations to accept Rhodesian self-determination as an international issue, a campaign during which he got a personal hearing before the General Assembly in 1962. The consequence was the immediate banning of the organization by the white government.

Nkomo continued to blast the white minority government until, in 1964, after calling for British military intervention, he was imprisoned at Gonakudzingwa. The detention order lasted ten years, through December, 1974, when South African Prime Minister John Vorster pressured Mr. Smith into releasing all the nationalist leaders under arrest as a prelude to a summit conference to settle the Rhodesian constitutional crisis.

But the government has not been the only obstacle to Nkomo’s leadership. The road has also been blocked by continuing divisions among black nationalists. Prime among these is the Rev. Ndabaningi Sithole, who broke with ZAPU in 1963 to form a more militant organization, the Zimbabwe African National Union (ZANU).

Over the interim 12 years, the split has deepened because of the two leaders’ personality clash and tribal divisions that have, generally, aligned the southern Matabele tribe with Nkomo and the northern Mashona with Sithole.

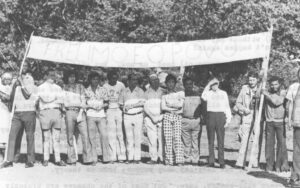

Under pressure from the presidents of Zambia, Mozambique, Botswana and Tanzania last December, the two factions — along with the smaller and almost insignificant Frolizi (Front for the Liberation of Zimbabwe) organization — merged under the umbrella of the fourth group, the non-violent African National Council. Bishop Abel Muzorewa was chosen as president. The merger was urged to present a united front in preparation for negotiations with the Smith government.

Under pressure from the presidents of Zambia, Mozambique, Botswana and Tanzania last December, the two factions — along with the smaller and almost insignificant Frolizi (Front for the Liberation of Zimbabwe) organization — merged under the umbrella of the fourth group, the non-violent African National Council. Bishop Abel Muzorewa was chosen as president. The merger was urged to present a united front in preparation for negotiations with the Smith government.

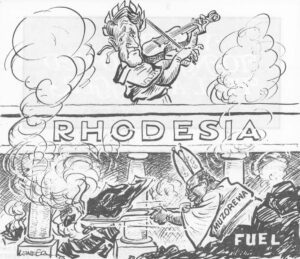

But soon after the first efforts at talks broke down at Victoria Falls on August 25, the old leadership and strategy squabbles surfaced again.

Of the four leaders, only Nkomo felt he could return to Rhodesia after the breakdown and not face further detention. Prime Minister Smith had made it clear at Victoria Falls that Sithole and James Chikerema, head of the Frolizi faction, would not be granted amnesty to attend the second or committee stage of negotiations within Rhodesia. In fact, it was over this issue that talks collapsed.

Nkomo’s subsequent speeches and campaigns within Rhodesia led Sithole to charge that Nkomo was making a secret deal with Rhodesian officials. Nkomo retorted that this was “absolute nonsense.”

Critics note, however, that while there was probably no explicit deal, Mr. Smith was implicitly aiding Nkomo by making it possible for the more moderate leader to move and speak openly at public meetings and to the press, to carry a passport, and to continue his political activities, despite the fact that it was to the detriment of the white government. On the other side, the three externally-based leaders were not even allowed into the country.

Exiled leaders then added to the growing tension by taking over the Zimbabwe Liberation Council (ZLC), pushing aside the ZAPU men on the council. The ZLC — based in Lusaka, Zambia — was established at the merger last December to direct external operations.

From his base in the southern Rhodesian city of Bulawayo, Nkomo blasted the organization and called for an executive meeting on Sept. 7 to discuss the issue. For his independent action and for ignoring the ANC constitutional procedures, Nkomo was expelled from the organization by Bishop Abel Muzorewa.

But the fiery figure went ahead with the conference anyway and managed to get a bare quorum (37 or 69 members), therefore declaring it legal. At the executive meeting, members decided to hold a national congress for all provincial members on Sept. 27-28. It was at this meeting that Nkomo was elected president.

The new president was not grabbing for power blindly by going against the ANC. A shrewd man, he knew at each step that he had the support of the majority of provincial leaders. He also knew that the four presidents who forced the merger last December would not try to stop him. Nkomo was their original choice for the ANC presidency. Only when ZANU threatened to walk out was Bishop Muzorewa selected as a compromise.

The change in leadership does not necessarily mean the nationalists will be any less adamant about immediate majority rule. The difference will be in strategy. As a white sympathizer explained:

“Nkomo has more patience. All of them know that Smith won’t give them what they are asking for. Nkomo is not a brilliant man, but he has common sense. He wants Smith to show that the whites are the real obstacle to settlement. This can only be done at another round of talks. Then the ANC will have all the support it needs, even from South Africa.”

Nkomo’s endurance and common sense are indeed his strongest qualities. Although well-educated — at Adams College, Jan Hofmeyer School and the University of South Africa — he is not considered an exceptionally bright man, not the caliber of President Machel of Mozambique, President Nyerere of Tanzania, or President Kaunda of Zambia.

He is not comfortable speaking on a stiff leftist ideological platform, as the other black nationalists are. He is considered more of a pragmatist, understanding the economic possibilities of Rhodesia and being realistic about the vital link with South Africa.

Nkomo moves step by step. After several interviews, it was clear that he was not willing to outline his program for Zimbabwe. “Let’s get majority rule first,” was his regular reply to inquiries. “Then we can work on equalizing the unequal distribution of wealth.”

The strongest outside influence on him is the Zambian president and it is expected that Nkomo would implement a system closer to the mild socialism in Zambia rather than the militant Marxism of Mozambique’s new government.

Nkomo has yet to specify his version of a Zimbabwe government. But whenever he leaves a question on the subject unanswered, a slow smile spreads across his large face and his eyes twinkle, indicating he knows more than he is telling.

Received in New York on October 6, 1975.

©1975 Robin Wright

Robin Wright is an Alicia Patterson Foundation award winner on leave from The Christian Science Monitor. This article may be published with credit to Robin Wright, The Christian Science Monitor, and the Alicia Patterson Foundation.