After 500 years of colonialism and ten years of a bitter guerrilla war the Portuguese territory of Mozambique becomes independent on June 25. Little has been written about the men who led the liberation struggle as members of Frelimo (Front for the Liberation of Mozambique) and who will soon take over the government after a short nine-month transition period. Robin Wright recently became the first foreign journalist to travel with Frelimo Prime Minister and several members of the transition cabinet as they toured the country. Before going to Mozambique, Wright also met with members of the party hierarchy who remained in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania during the transition. What follows is an assessment of the key leaders, who will play a vital role in the future of all southern Africa, as well as in Mozambique, due to the country’s strategic position and its long-standing economic ties with South Africa and Rhodesia.

Lourenco Marques, Mozambique

One is an author. Three are former professors or instructors. Two are lawyers. One was a newspaper editor, another an engineer, and several are published poets.

The elite of a social club? A bank’s board of directors? Members of a citizen lobby?

Hardly. These are the “militants” of Mozambique, the men who directed the guerrilla war to free the massive southeast African country from 500 years of Portuguese domination and who are now stepping in to form the new government.

Hardly. These are the “militants” of Mozambique, the men who directed the guerrilla war to free the massive southeast African country from 500 years of Portuguese domination and who are now stepping in to form the new government.

Although known world-wide as an effective military organization, Frelimo (Front for the Liberation of Mozambique) is not yet widely recognized as an efficient political organization. Yet as the above titles suggest, there is much more behind Frelimo than a few thousand guerrillas fighting in Mozambique jungles.

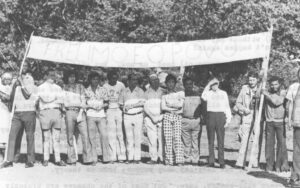

In fact, since Frelimo held its second Congress–the highest policy-making body–in 1968 the movement has put as much emphasis on reconstruction of the liberated areas as on the guerrilla campaign. Health facilities, schools, agricultural cooperatives and judicial and administrative systems were set up in four of Mozambique’s provinces. These programs–affecting just under ten percent of the nine million population–are a microcosm of what Frelimo must now do on a national level. Thus the leadership is not in a “guns to government” situation, but has a degree of experience in the tasks it now faces, an unusual edge for a liberation movement on the eve of independence.

In addition, Frelimo has established a sophisticated set of statutes and programs that will easily evolve into a constitution with the addition of fundamental laws. One knowledgeable foreign observer who has closely followed Frelimo since it was founded in neighboring Tanzania 13 years ago remarked recently: “Frelimo is clearly as political as any long-established party or movement on the continent.”

There are many problems of course. First, there are clearly not enough trained and experienced men to step in. And with the massive exodus of Portuguese, there are not enough back-up civil servants to work until people can be trained. Many members of the new administration at the intermediate levels are “prison graduates”–former political prisoners–or lower level civil servants who were not allowed to rise under the Portuguese government. And the new government is noticeably young. Not one of the top men is over 45 and most are in their mid-30s. At the lower levels many are in their 20s.

The movement argues vehemently that the leadership is collective, pointing as proof to its three top policy-making bodies–the Central Committees Executive Committee, and Political-Military Committee–on which anywhere from nine to 42 individuals jointly decide on issues. Yet there are only four men who serve on all three committees and a closer look at each reveals the type of people who will wield the most influence on policy matters in independent Mozambique.

Samora Moises Machel

Despite Frelima’s claim that leadership is collective, it would be hard to deny that Samora Machel is considered the national hero and leader. His picture and the Frelimo flag are omnipresent in Mozambique–on every storefront window, every sidewalk billboard, on 20-foot posters at May Day celebrations, in newspapers almost daily–and he is saluted in the score of songs, slogans and chants that are now part of all school sessions, party meetings and public rallies. Machel is probably better known at this point than Eduardo Mandlane, the father of the Mozambique revolution who in 1962 organized the many factions of the liberation movement into a united front.

Elected to the presidency in 1970, one year after Mondlane’s assassination by a mail bomb on February 3, 1969, the charismatic leader’s short academic career led some outsiders to question the movement’s decision in light of the many more “credentialed” men available. His formal education ended after four years of primary school and until joining Frelimo in 1963 he worked as a male nurse and medical assistant in a Lourenco Marques hospital. In contrast, Mondlane had a B.A., M.A., and Ph.D. from top American universities, had taught sociology at Syracuse University, and had worked on the United Nations staff. Yet in his five years as President Machel has gained a degree of popularity and respect that makes his position unchallenged.

The lean, 42-year-old president’s original role was purely military. Among the first cadres sent to Algeria in 1963 for guerrilla training, he set up the first Frelima training camp upon his return to Tanzania. In 1966 he became Secretary for Defense–making him eligible for membership on Frelimo’s top three policy-making bodies–and in 1968 he was appointed Commander-in-Chief of the armed forces, again increasing his political as well as military responsibilities. For a year prior to his election as president he served on the Council of the Presidency that was formed after Mondlane’s death, sharing office with two more seasoned or “credentialed” men.

A man of action rather than words, Machel continued even after the war to wear his battle fatigues and eat and work among the soldiers he directed through much of the war. During the transition he spent as such time at Nachingwea, Frelimo’s military headquarters in southern Tanzania, as at the Mozambique Institute, where most of the remaining hierarchy worked. His easy, almost boyish smile and “talking” eyes have given him the reputation of a comfortable and approachable leader, despite the fact that he shuns the limelight and all press interviews.

On the rare occasions he does talk to the press, the reasons for his appeal become obvious to outsiders. While intent and articulate, he is also disarmingly friendly and open, acknowledging the specifics of problems that could just as easily be left vague. He knows his facts and figures, although getting specifics about solutions is another matter. Throughout the transition the Frelimo leadership was closemouthed about the various alternatives open to the post-independence government. They would not even disclose the date of their return to Mozambique from Dar es Salaam headquarters. When asked about the arrival–his first trip to the capital since his departure to join Frelimo 12 years ago–Machel’s face broke into a mischievous grin, eyes twinkling, “For independence, of course.” He obviously enjoys the drama of his new role.

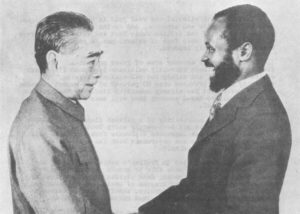

Marcelino Dos Santos

Poet, Ph.D. and professional diplomat, Marcelino Dos Santos is a perfect counterpart for the rugged Machel. The neatly bearded Vice President is a quiet and methodical theorist educated in Lisbon and at the Sorbonne who has had his poetry published in French, English, Portuguese and Russian. His activism in the liberation struggle goes back the furthest of all those in the current Frelimo hierarchy, beginning when he was elected Secretary-General of the Conference of Nationalist Organizations in the Portuguese Colonies in 1961.

As a back-up to Mondlane, Dos Santos played an essential role in the merger of three parties into Frelimo in 1962 and in the development of the movement into a stable force that could open up a military campaign two years later.

From 1965 to 1970 he served as Secretary for External Affairs and was highly effective in using his international reputation and contacts to rally support and funds for the growing movement. He continued the diplomatic role right through the transition period and is expected after independence to serve as Foreign Minister or representative to the United Nations or Organization of African Unity.

Although reputed to be ideologically aligned with the Soviet Union, he actually has solid contacts with both East and West. In 1970 he gained recognition from the Pope when he was received at the Vatican and given a copy of the papal encyclical Populorum Progressio on the problems of the underdeveloped world. The following year he received the Lenin Centenary Medal.

Although a low-key figure in contrast to the other three–contributing to his recent shadow position he has often shown the depth of his feeling in poetry about the liberation struggle, even before Frelimo was founded. In 1953 Dos Santos wrote:

No

seek me not

in places where I don’t exist.I live

hunched over the earth following the path cut by the whip

on my naked backI live in the harbours,

feeding the furnaces,

driving the machines,

along the paths of menI live

in the body of my mother,

selling her strength in

the market place…I live

lost in the streets

of a civilization

that crushes me with hatred

and without pity.And if it is my voice that is heard,

if it is I who still sing,

It is because I cannot die,

But only the moon hears my anguish…

Joaquim Alberto Chissano

Slight in figure, young in age, Joaquin Chissano is hardly the figure of a statesman. Off-stage he is soft-spoken, almost shy, rarely the aggressive politician, and anything but the image of the dynamic force needed to pull a new nation out of 500 years of colonialism.

Yet in Joaquim Chissano Mozambique has as strong and forceful a leader as there is in Africa. Of the four key figures in the new government the 35-year-old Prime Minister has the most experience in both party and government matters. While Machel and Dos Santos sat out the nine-month transition period in Dar es Salaam, Chissano did the grueling legwork in Lourenco Marques–assessing the nation’s problems, negotiating with the Portuguese and organizing programs for approval in Dar es Salaam.

Yet in Joaquim Chissano Mozambique has as strong and forceful a leader as there is in Africa. Of the four key figures in the new government the 35-year-old Prime Minister has the most experience in both party and government matters. While Machel and Dos Santos sat out the nine-month transition period in Dar es Salaam, Chissano did the grueling legwork in Lourenco Marques–assessing the nation’s problems, negotiating with the Portuguese and organizing programs for approval in Dar es Salaam.

Chissano won the top ministerial post–and his reputation as the most competent administrator in Frelimo–as a result of his performance during 12 years in Dar es Salaam, where he served as Frelimo, Defense Minister and Executive Secretary. In the defense post he was responsible for coordination of the ten-year guerrilla war against the much stronger Portuguese forces. In the latter role he controlled the party purse strings and decided priorities for the use of available funds. He also served as the official representative of Frelimo in Tanzania, a post of special diplomatic importance.

A moderate with no strong ideological ties to either the Soviet Union or China, Chissano is also the most pragmatic of the top four about his country’s future and the necessity for compromise until Mozambique is economically self-sufficient. While Machel takes a stiff line on aiding other liberation movements, the sources of foreign aid or investment, and the farm revolution, Chissano has acknowledged the reality of the moment–that some form of ties with South Africa will be necessary for at least the short term, that the gravely troubled economy will need any aid offered, and that the farm revolution will take time.

Although long acknowledged as the number three man, Chissano has maintained a low profile throughout his involvement, even during his many missions abroad to explain the Front’s economic, education and health programs to would-be sympathizers and potential supporters. He did not surface as a key figure until he was sent to open secret negotiations with the Portuguese in June, 1974. He remained the key Frelimo negotiator throughout the talks, the talks that led to an agreement on Mozambique’s independence, signed in Lusaka, Zambia last September 7. With less than one week’s notice he was then selected as Prime Minister and led Frelimo’s representation on the transitional government to Lourenco, Marques for installment on September 20.

At the time of the investiture a European diplomat in Dar es Salaam, who had known Chissano for several years, predicted: “He will certainly not have the opportunity to construct a political base as Prime Minister during the coming nine months until independence because of the confusion he presently has to solve.” Yet well before the nine months were up the energetic and charismatic figure was acknowledged to have a tight hold on the post–and to have done sufficient work to insure a peaceful and easy transition on June 25. Songs heralding Chissano are now as common as those saluting Machel, and he is probably better known in Mozambique than Dos Santos.

Yet the agreeable, easy-going politician is not considered a threat to either of the party’s top two figures, despite the fact that he offers a blend of both men’s strengths. Like Machel, he is a youthful and energetic figure of immense popularity who prefers to mix with The People as much as possible. At dinners on a recent tour of the rural areas he would sit at a table separate from other officials and chat easily and make jokes with whomever sat down. And his academic training in Lisbon and Paris–he speaks English, Portuguese, French, Swahili and several local dialects fluently–have won him the reputation of an intellectual.

It seems clear that Chissano prefers the secondary role, and strongly supports the movement’s claim that leadership is collective. He repeatedly contends that his role as Prime Minister during the transition has been merely advisory, serving as the eyes for the Dar es Salaam-based leadership. But his experience during the transition will clearly put him in an unrivalled position as the most experienced man in the new government.

Armando Guebuza

Armando Guebuza, the boyish-looking Minister of Internal Administration and Political Commissar, is the youngest member of the top four at the age of 31. Yet as a member of the top three policy-making bodies he is clearly as powerful in behind-the-scenes maneuvering. And his role in the transition government as Prime Minister Chissano’s right hand man and number two in the cabinet has made him even more important to the party–and the future of his country.

Probably more important than his ministerial post is his role as Political Commissar, a job which puts him in charge of politicizing the masses through the “dynamization” program that organizes circles or cells for “mentalizing” people to Frelimo’s policies. Diplomats and foreign observers concede he has made extraordinary progress in selling Frelimo to many segments of the nine-million Mozambique population. Many feel this will be a key factor in avoiding the type of incidents at independence that troubled the new government during the transition last September and October.

Probably more important than his ministerial post is his role as Political Commissar, a job which puts him in charge of politicizing the masses through the “dynamization” program that organizes circles or cells for “mentalizing” people to Frelimo’s policies. Diplomats and foreign observers concede he has made extraordinary progress in selling Frelimo to many segments of the nine-million Mozambique population. Many feel this will be a key factor in avoiding the type of incidents at independence that troubled the new government during the transition last September and October.

As the result of several tours throughout the country during the transition period Guebuza has become a well-known and popular figure, as evidenced in the new crop of songs that salute him. Like Machel, he has a fiery charm that erupts when he gets in front of a crowd, much more so than Chissano. A master of party rhetoric, he can outline Frelimo policy in simple and appealing terms, often in local dialect, drawing wild responses from the crowds.

Behind his youthful look and easy smile is a sophisticated, hard-line theorist, perhaps the fiercest ideologist among the top four, who cleverly but firmly argues the stiffest implementation of party policy. He will startle a questioning skeptic by stating almost as fact, “You do not really believe that,” or “You know better than that.”

Guebuza was born in Marrupa, in the northern Nampula province, making him the only member of the four not born in the South. This could be a significant factor in dealing with the independent Macua tribe, Mozambique’s largest and constituting almost one-half the population, who live in the North.

The Political Commissar was educated, however, in Lourenco Marques and was active as a youth as president of the African Secondary School Students’ Center. At 19 he joined Frelimo and his rise to the leadership was fast.

A poet, with works published in Portuguese, English and Russian, his poetry reflects the fierceness of his loyalty to the liberation struggle. In the mid-60s he wrote:

The War

If you ask me

who I am,

with that face you see, you others,

branded with marks of evil

and with a sinister smileI will tell you nothing

I will tell you nothingI will show you the scars of centuries

which furrow my black back

I will look at you with hateful eyes

red with blood spilled through the years

I will show you my grass hut

collapsed

I will take you into the plantations where

from dawn to after night-fall

I am bent over the ground

while the labor

tortures my body with red-hot pliersI will lead you to the fields full of people

breathing misery hour after hourI will tell you nothing

I will only show you thisAnd then

I will show you the sprawled bodies

of my people

treacherously shot

their huts burned by your peopleI will say nothing to you

but you will know why I fight

Joaquim Carvalho and Jorge Rebelo

Although neither Joaquim Carvalho nor Jorge Rebelo served as members of the transition government, both are members of Frelimo’s Central and Executive Committees and have played vital behind-the-scenes roles for the new government. Both are men to watch for.

Jorge Rebelo, a trained lawyer and poet, directed Frelimo’s highly effective propaganda campaign during the war as editor of Mozambique Revolution and author of several other party documents. He is a quiet figure who remains in the background as much an he can, yet is known to be a key advisor to Machel. Likely to remain a party rather than government leader, his influence is certain to be felt on all major policy decisions.

The importance and appearance of Joaquim Carvalho is also certain to increase after independence. Considered by all diplomatic and party sources to be the chief economist and designer of the new government’s financial programs, he will have the tough chore of pulling together Mozambique’s gravely troubled economy. At independence the country will face external debts of close to $950 million, not helped any by an acute shortage of foreign reserves.

One foreign observer who has followed Mozambique’s economic status closely for five years said of Carvalho: “He is the most influential and able economist Frelimo has and his role can only increase.”

Received in New York on May 12, 1975

©1975 Robin Wright

Robin Wright is an Alicia Patterson Foundation award winner on leave from The Christian Science Monitor. This article may be published with credit to Robin Wright, The Christian Science Monitor, and the Alicia Patterson Foundation.