One of the forgotten factions in the current phase of Rhodesia’s constitutional crisis is the African living in the “sharp end” — the zone where terrorists have been sporadically active since December, 1972. Some 100,000 black Rhodesians live in this northeast border area and have had to face two ugly alternatives during the past three years: support the guerrillas and face retribution from the government, or support the white government and face retribution from their own people.

Over the past eighteen months the government of Prime Minister Ian Smith has acted to enforce a decision in its favor by establishing “protected villages” camps surrounded by barbed wire and guarded by the Rhodesian army. Most of the Africans in the north have now been relocated into these new villages and are cultivating their first crops.

Robin Wright recently flew to the “operational zone” in the North and toured the facilities. Based on interviews with field workers, families in the kraals (villages), army and government officials and black nationalists, Wright offers the following assessment of Rhodesia’s latest effort “to protect both itself and the African population.”

Fort Mopani, Rhodesia

Deep in the fertile Zambesi Valley, less than two miles from the Rhodesia-Mozambique border, the richly wooded terrain suddenly breaks and a massive, barbwire-fenced village comes into view. Tightly guarded by Rhodesian soldiers, it could pass as a detention camp, army station or frontier outpost.

But it is none of these. The site is one of Rhodesia’s now “protected villages” — the camps set up in the area of terrorist activity to guard the local population from assault — and one of the most controversial measures enacted by the government of Prime Minister Ian Smith in recent months.

But it is none of these. The site is one of Rhodesia’s now “protected villages” — the camps set up in the area of terrorist activity to guard the local population from assault — and one of the most controversial measures enacted by the government of Prime Minister Ian Smith in recent months.

The establishment of these villages is the reaction of the white government to guerrilla attacks in the area, which have been sporadic since December, 1972. Officials contend they were built to protect the defenseless local black population. But critics charge they were constructed to protect the government by separating the freedom fighters from a vital base of support.

In the past, Africans in the rural kraals (villages) have been a source for food, supplies, cover and now recruits. The new villages cut off this aid and allow the Rbodesian Army — which guards the sites and organizes all aspects of life — to keep a watchful eye an movements in the area.

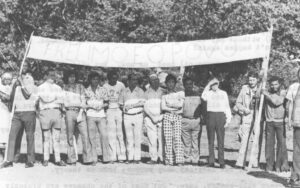

Fort Mopani is just one of several sites in the “sharp end” where villages have been established. Set among Mopani, acacia and baobob trees are two clusters of 2,000 people each. Residents live in the traditional wood and thatch huts and work on new fields being cultivated outside the barbed wired enclosures.

District Commissioner Jim Latham contends the village chiefs appealed to the government for protection and agreed to the move to new settlements. He says no one was moved against his will, although people in some kraals had to be persuaded to move earlier than they wished.

But a recent investigation by the Catholic Commission for Peace and Justice led to charges that security forces have used torture — including sticks and electric prods — against residents not willing to move. According to the Commission, the new government program has shattered the Africans’ well-organized family and social systems, and has disoriented and alienated the local population.

A prominent black Rhodesian political scientist, who has visited the new sites, added that “It is no exaggeration to call them concentration camps. They are rural slums — overcrowded, without basic facilities and unhealthy. The government could have done much better. All they have done is alienate these people by taking away their autonomy and forcing them into undesirable lifestyles.”

Government officials acknowledge there is a “slight departure from the normal regulation scheme” of the tribal trustlands, the rural black settlements throughout the country. Among the measures: a dusk to dawn curfew, registration of all people over thirteen years of age, and regulation of all people passing in or out of the camps.

And the army presence is blatant. In the fields, armed black soldiers walk in front of and behind the workers as they till the land with hoes, directing action through a loudspeaker. Guards oversee all construction projects. And scattered around the camp are tents housing the soldiers who guard the villages at night.

Commissioner Latham says the army will soon withdraw “as much as possible” from internal projects and leave the villagers to manage themselves. Many soldiers, however, will remain to guard the site from intrusion by terrorists crossing the border from Mozambique.

But the army cutback does not satisfy some of the new residents. As one elderly women explained: “This is not my home and I am not happy here. I don’t want to work with the army keeping constant watch over me. At my (former) home, where my family has lived for generations, I grew enough to live and I never helped any terrorists. So why did I have to come here? I am being punished only because I live in this part of the country.”

The women’s remark reflects a second and more subtle issue than the dispute over government motive and manner in building the villages. More annoying than the barbed wire fences and relocation is the outside interference by whites and the superior attitude accompanying it.

White officials contend they are trying to improve the life of the rural African, but rural blacks generally are not interested in changing the manner in which they live.

A statement by a district official at Fort Mopani typifies the white position: “We are trying to help these people, but we who have been here all our lives know these chaps pretty well. Their only aspiration is to sit in the sun and do nothing. We want to show them a better way, but it is difficult.”

The African — whether due to apathy, tradition or resentment of outside interference — has balked at the changes introduced in the protected villages. There are definitely some benefits to the scheme: agricultural experts assigned to the camps say it is easier now to improve farming practices. Providing scarce water supplies, and health and educational facilities is easier due to the tighter concentration of the population.

But self-sufficiency is the local African’s main goal and he has little incentive for more, especially if the advanced techniques involve control from outside.

The trauma of changing location and the traditional lifestyle may actually backfire on the government. As the political scientist explained:

“The resentment could push more people into support for the freedom fighters. This new program accentuates the type of intimidation of blacks by whites that had previously been felt only in the urban areas.

“You can see already that there are mainly women and children in the villages. Many of the men have left to join the guerrillas and more will probably join as a reaction to the increasing restrictions and interference in their lives.”

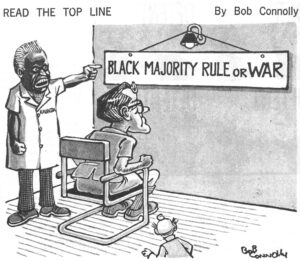

Ultimately, these “protected” Africans have two unpleasant alternatives from which to choose: support the guerrillas and face retribution from the white government, or support the government and face retribution from their own people.

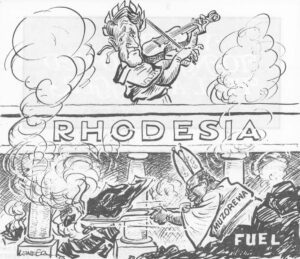

But there is still time. Terrorist activity in the northeast is minimal since most freedom fighters are being held in Mozambique and Tanzanian training camps while negotiations continue between Prime Minister Smith and the African National Council. Only if the effort to reach a peaceful settlement of the decade-old constitutional dispute fails will the black nationalist troops be released.

Meanwhile, the government is attempting to build what one black nationalist called a “prevention system” — structures to exclude the northern blacks from all opportunities to help or back the guerrilla effort, and thus endanger continued white minority rule.

Received in New York on January 5, 1976

©1976 Robin Wright

Robin Wright is an Alicia Patterson Foundation award winner on leave from The Christian Science Monitor. This article may be published with credit to Robin Wright, The Christian Science Monitor, and the Alicia Patterson Foundation.