Portugal was the first colonial power in Africa, dating back almost 500 years. With the independence of its three African colonies — Guinea-Bissau, Mozambique and Angola — this year it will be the last major colonial power to leave. But the break does not end all ties, for not all the Portuguese have yet left.

In Mozambique, for example, the Portuguese are not typical settlers. While most African countries were “settled” by whites in the early 1900s, the whites in this massive southeast African country go back many generations. Most consider themselves Mozambicans.

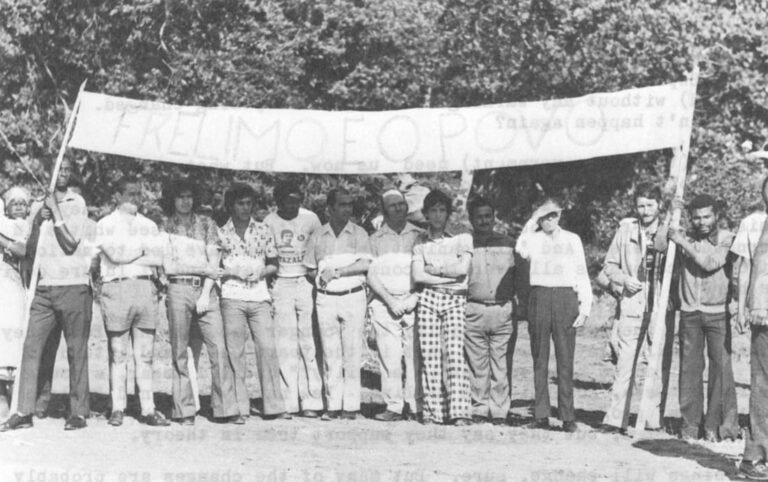

But even as Mozambicans they have many questions about life under the new Frelimo (Front for the Liberation of Mozambique) government. The fears and hopes are strong since the full implications of independence will be unknown for the first year — or years.

Robin Wright has spent three months in Mozambique writing about the dismantling of the Portuguese empire. Wright’s investigation has included an examination of the Portuguese community and what follows is an assessment of their feelings about their future in Mozambique.

Lourenco Marques, Mozambique

Rita moaned, “What am I supposed to do? I want to stay in Mozambique. My family, my home, my work are here. But I am afraid. I don’t know of what specifically. I guess the possibilities.”

“I am afraid there will be many cases of reverse racism, no matter what the government says. I know the intentions are good. I believe Frelimo supports multi-racialism, or non-racialism, as they say. But the masses don’t see it that way yet.”

“To them independence means recognition for those who were oppressed. In other words, the blacks. I don’t blame them. I’d be the same way if I were in their position. But I’m not. What would you do?”

That is a question many Portuguese are trying to answer as the Portuguese government officially ends 500 years of colonial domination with the independence of Mozambique on June 25.

At least one-half the white population has already chosen to find new homes elsewhere, mainly in Portugal, South Africa and Brazil. According to the Portuguese High Commission, at least 103,000 have fled from Mozambique since January, 1973, leaving anywhere from 70,000 to 100,000 in this southeast African country of nine million. Illegal emigration and “vacationing” whites have made exact figures impossible to obtain.

Of the 103,000, about 30,000 left in 1973 as the ten-year war between Frelimo guerrillas and Portuguese troops spread further south. Between January, 1974 and the military takeover in Lisbon on April 25 another 20,000 left.

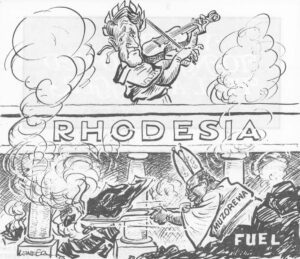

The main exodus came after September, 1974 when two white-initiated incidents frightened the remaining white community. In September, white extremists seized a Lourenco Marques radio station in an abortive bid to prevent Frelimo from coming to power. White mobs roamed the town and many Africans were killed.

In October, Portuguese soldiers picked a fight with Frelimo guerrillas in the main district of the capital city, sparking a gun battle that led to the deaths of an estimated 47 whites. Fearing a backlash, at least 52,000 have since left.

Although things have been peaceful since then and few now anticipate trouble at independence or immediately afterwards, many are still afraid.

The new government has long maintained that Mozambique will be a multi-racial state. As Prime Minister Joaquim Chissano said recently:

“It is not color that exploits and oppresses people, it is a system. Color alone does not divide. It is ideas, not color, that count, and anyone who has the right ideas, who wants to work, is welcome to stay.”

“Frelimo fought to establish equality, so we will not refuse equality to those who refused it to us. We need everyone for the work ahead of us.”

But words are not enough to soothe the fears of many of the whites remaining in Mozambique. As a Lourenco Marques businessman explained:

“The Portuguese said they would never leave us too. But they sold us out last September (when the agreement to give Mozambique independence was signed) without any warning. Overnight everything changed. Who says it won’t happen again?

“They (the new government) need us now. But what about when (black) people are trained for our positions? Look at every other African country. Ghana, Nigeria, Tanzania, Kenya, Uganda — they all promised multi-racial societies. But how often do you see whites in governments there? And Africanization programs have led to nationalization of companies all Over the continent. What kind of future do I have here?”

Many of the whites, especially the younger generations, feel they definitely will play a crucial part in the years ahead and intend to stay. “What do we have to fear — equality?” queried Cesar, a young steward for Deta, Mozambique’s airline. Few have yet joined Frelimo’s “dynamization” programs, the cells formed to “mentalize” the people to Frelimo policies, but they say they support them in theory.

“Things will change, sure, but many of the changes are probably overdue. We never did anything to help the poor because we did not have to. No one really forcefully encouraged it, so we did nothing,” Cesar explained.

“I’m just as scared as anyone of losing the material advantages I’ve had. But in my conscience I cannot fight it.”

The fear has so far been mainly expressed by the older generations. “Most of my friends plan to stay,” the steward said. “It’s our parents who talk about leaving. They were comfortable under the Portuguese, whether they liked the government or not.”

Rita’s reaction explains much of the dilemma: “No, I don’t think there will ever be any overt action against us. It’s the by-products of ‘the revolution’ that worry me.”

“My children, for example, they won’t have the quality education any more, partly because many of the trained teachers have left, and partly because the new schools will be geared to the masses, who are at a much lower level.

“Already the subjects have changed from world history to Frelimo’s history — the war, writings of their leaders, and the independence agreement. That’s fine to learn more about Mozambique, but Mozambique and Frelimo are not all there is to the world.

“And when they finish school, what will job prospects be? Will they have equal opportunities? Or will the government and businesses want to put in as many of those who were formerly oppressed, the blacks, as possible? I don’t have the answers to those questions. It’s not my life I must think about, it’s theirs too,” explained the middle-aged mother of four.

Reverse racism came up again. “I worry about subtle harassment too. It could make life uncomfortable. Maybe my husband’s store will be boycotted for the new black-run businesses. Already my house servants are being arrogant, and sometimes not even showing up. I don’t dare fire them. Dismissing people looks bad in Frelimo’s eyes. They call it economic sabotage. I’m stuck.”

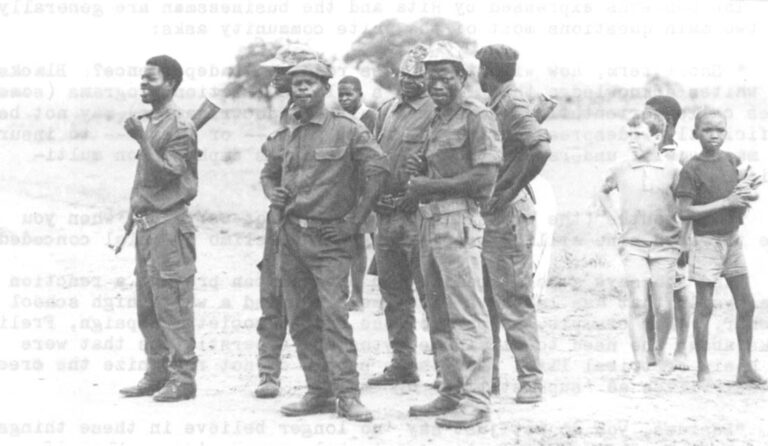

Some charge that the “subtle harassment” has already started. Antonio, a self-employed filmmaker told of one such incident:

“This morning I was rudely awakened by a Frelimo soldier. He told me he had a watch but no band and wanted 100 escudos ($4) to buy a band.

“Now, I thought, I could easily call the authorities and he would be punished as Frelimo tends to take a stiff line about such activities. But I also know that after independence, after June 25, that fellow would remember me and my house if he didn’t get what he wanted. And then what? I’m a coward. I don’t want trouble. I don’t want them to think I’m against the new government. I want to stay here in peace. So I gave him 20 escudos (80 cents) and he left.”

The concerns expressed by Rita and the businessman are generally the two main questions most of the white community asks:

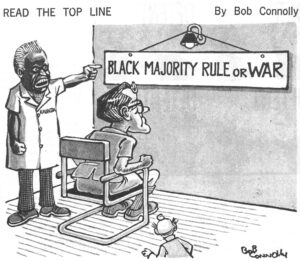

- Short term, how will the masses react to independence? Blacks and whites acknowledge that Frelimo’s politicalization programs (sometimes called orientation, sometimes called indoctrination) may not be sufficiently widespread during the first year — or years — to insure the masses will understand the new government’s emphasis on multiracialism.

“Nine months (the transition period) is not very long when you have to reach nine million people,” a young Frelimo official conceded.

“And who says a politicalization program can prevent a reaction to a system that has lasted a lifetime?” worried a white high school teacher. “For example, as part of the united society campaign, Frelimo talks about the need to eliminate myths and superstitions that were the basis of tribal life. But these people do not recognize the creeds of their lives as ‘superstition’ or ‘myth.’

“Besides, you do not just say ‘no longer believe in these things’ and expect them immediately to accept whole new system. What if you said to Christians ‘no longer believe in Christ or his teachings.’ Hah. It does not work that way.

“You have to give them some alternative. Unfortunately, what is taught is often too abstract for many of them. All this philosophy is not tangible yet.”

- Long term, will the small one percent white population slowly be phased out of their jobs, homes and other material advantages they have traditionally held has been the case in many African countries?

“It would not be outright,” a Portuguese-born banker predicted. “But maybe we will not be allowed to make the money needed to maintain our lifestyle. We could elsewhere, so what is the reason to stay here?”

The new government has tried to alleviate these concerns through specific actions as well as strong declarations. Recently Frelimo agreed to allow many whites in key government and business positions to deposit 25 percent of their incomes in foreign banks as an incentive to stay. And already several sources both inside and outside the government estimate that 15 percent of the new faces in government are white.

The government has also quietly welcomed back the estimated 250 white Mozambican exiles who have returned from Portugal, Brazil, South Africa, Rhodesia and other European countries. Many more are expected after independence.

Both government and Portuguese sources agree that there is greater hope for an integrated society in Mozambique because of the long history of Portuguese presence. The Portuguese represent an unusual case of colonialism in Africa. In the majority of countries, the settler communities date back only to the early 1900s, since most of the continent was divided up by European powers after 1850.

But the Portuguese presence dates back almost 500 years, to Vasco da Gama’s ‘discoVery’ of the area in 1498. Lourenco Marques brought the first whites to the southeast African country in 1544. Most white Mozambicans are at least fourth generation; many go back farther than current residents can trace. They often have no formal or familial ties with Portugal beyond the language.

But the Portuguese presence dates back almost 500 years, to Vasco da Gama’s ‘discoVery’ of the area in 1498. Lourenco Marques brought the first whites to the southeast African country in 1544. Most white Mozambicans are at least fourth generation; many go back farther than current residents can trace. They often have no formal or familial ties with Portugal beyond the language.

In fact, some whites contend that being born in Mozambique made them “second-class Portuguese. One young white engineer explained:

“Many of us are just as happy to get rid of the Portuguese government and their people. They always acted superior, mixing only among themselves, as if being born here made us less important, as if we had less potential than those from Lisbon. Now I can be proud of my place of birth.”

The current feeling among most Portuguese and foreign observers is that the mass exodus has ended. “Those who wanted to leave are gone. The rest will probably stay,” a foreign diplomat suggested.

For many the decision to remain appears to be voluntary. Others say it would now be difficult to depart even if they wanted to.

“Our money is worthless elsewhere. One million escudos would not buy a bandaid outside Mozambique,” a white hotel manager said. “And visas are now very difficult to obtain, except to Portugal.”

South Africa, one of the main alternatives, drastically cut back on visas in the months just before independence. Although the white-minority government backed the Portuguese during the war, it now wants to establish good relations with Frelimo because of the strong economic ties with Mozambique, involving railways, ports, mineworkers and hydroelectric power sources. Indirectly offering a refuge for potential refugees is not a way to stabilize the situation in its neighboring nation.

But equally important is the question of where to move. “I don’t know where I’d go if I had to,” an architect commented. “Portugal has its own problems. And I probably couldn’t find employment there. Going to Angola is asking for trouble. And in South Africa or Rhodesia there is a language barrier. Besides, there may be trouble in both places eventually.”

Most contend they will stay in Mozambique, despite qualms. The attitude was summed up by a white geologist: “I want to be part of the new Mozambique. I want to see it work. I believe what Frelimo wants is right. But until I see whether it works I am going to keep my Portuguese passport — just in case.”

Received in New York on May 27, 1975.

©1975 Robin Wright

Robin Wright is an Alicia Patterson Foundation award winner on leave from The Christian Science Monitor. This article may be published with credit to Robin Wright, The Christian Science Monitor, and the Alicia Patterson Foundation.