A Morning’s Journey on December 31, 1969, into the Lagoon at Grand Gaube, a Fishing Village at Cap Malheureux on the Southern Indian Ocean Island of Mauritius

Cast of Characters

| Octavius Antonius Marie (Octave), age 27 | An unemployed Creole stone mason who has taken to the sea |

| Karl Latchoo, age 26 | A Creole fisherman |

| George Francois, age 17 | A neighbor youth, who serves as their boatman |

| Dhanilall Thug (Prem), age 22 | A destitute Hindu student |

“Riders on the earth together, brothers in that bright loveliness in the eternal cold….”

Archibald MacLeish, inspired by man’s first televised view of earth from the moon, Christmas, 1968

|

(Introductory note: The tiny, twenty-nine-mile wide island of Mauritius is one of a scattered group known as the Mascareignes, situated on the Tropic of Capricorn in 20 degrees of southern latitude, some 1,200 miles oat into the Indian Ocean from the east coast of the African continent. An isolated remnant of a vast geological upheaval of uncertain antiquity, the island itself is the exposed tip of a volcanic colossus jutting up from the floor of the oceanic abyss 2,000 fathoms below. Its 100-mile coastline is almost entirely ringed with coral reefs enclosing lagoons of brilliant clear blue-green water. Green, mountainous and lovely, known for its waterfalls, shooting stars and rainbows, the island was settled by the French in the 18th century who brought slaves from Africa and, after the British seized the island in 1810 and abolished slavery, indentured Indian sugar cane laborers from Bombay and Calcutta. A much-storied island visited by Charles Darwin, Joseph Conrad and Baudelaire and the setting of Bernardin de St. Pierre’s classic romance, Paul et Virginie, Mauritius has remained virtually undiscovered to many in the West. It received its independence from Britain in 1968 and recently caught some attention in the United States when it granted harbor facilities to the Soviet fishing fleet. This could have strategic significance since Mauritius lies on what has become the chief trade route between Europe and Asia now that the Suez Canal is closed. Development economists are more familiar with Mauritius as an island that is perhaps suffering the first true Malthusian breakdown in history. The island’s present population of 850,000 has more than doubled since malaria was eradicated with DDT 19 years ago. The economy is based entirely sugar which provides 98 per cent of exports. Most food has to be imported. Emigration has not proved a solution. The island is divided among five races: 20,000 whites of French descent, 25,000 Chinese, 120,000 Moslems of mixed Indian-Arabic blood, 250,000 Creoles of mixed French-African blood and 400,000 Hindus of Indian descent. Few nations have welcomed any but the whites. At present one man in three on the island is unemployed, including some 15,000 high school graduates. For the past two years real income has declined spectacularly* Moreover, since the five races are not integrated and European, Indian, Chinese, African and Moslem faiths, customs and cultures exist side by side, the danger of division and communal conflict is growing. Most critically affected have been the island’s Creole fishermen, for, as the ranks of the jobless have grown, more and more men have turned to the sea to feed their families. But they do not have large enough boats or motors to go beyond the reef and the lagoons are badly depleted; in the past three years the average daily catch has fallen 50 per cent. The following sketch is an attempt to portray part of a typical day in one of the island’s fishing villages; it is part of a general study, an exploratory expedition really, that will eventually embrace villages in the Punjab, Java and the Nile delta. The basic assumption of the study is that despite the revolution in seeds and methods of cultivation how sweeping the poor countries, the problem of problems for mankind remains that of too many people. I use the word “people” not “population” intentionally. For I believe that whether the coming revolution is “green” or “red” depends to a great extent on what goes on in the minds of educated, jobless youths like Prem with all their frustrations and middle-class aspirations and of men like Octave, who, although existing in what Oscar Lewis has called the culture of poverty, possess their own tragic awareness of the reality around them. Finally, it should be said that Grand Gaube exists, an actual fishing trip is described just as it happened and that Prem and Octave are real people. If you were in Grand Gaube tomorrow morning, they would almost certainly be delighted to have you sail with them into the lagoon. RC) |

Riders Together

Guide par ton odeur vers charmants climate

Je vois an port rempli de voiles et de mâts

Encor tout fatigues par la vague marine

Pendant que le parfum des verts tamariniers

Qui circule dans l’air et m’enfle la narine

Se mele dans mon âme aux chants des mariners.*

From “Parfum Exotique,” a description of Mauritius by Baudelaire

Ah! Mon Village

Comme tu es beau

Quand le ciel est sans nuage

Et avec tous ces chants melodieux des corbeaux

From “Mon Village,” by George Stephen Fanfan,

A fisherman of Grand Gaube

Always when the day begins, Octave rises from his bed and goes to the open door of his family’s fishing hut to search the sky. This morning the air was cool and fresh, swept by a slight southeasterly trade wind. The sky was just beginning to gray over the stars and a pale, late quarter-moon looked insubstantial and thin. The village was already awake even though only the sky showed the approach of dawn. Octave could hear the voices of fishermen and the splash of cars from the cove. Some of the pirogues were moving into the lagoon. He quickly palled on a pair of ragged shorts and harried to a neighboring hut. Octave’s gruff bark of “George” was answered by a muffled groan from within and he returned home where his mother was preparing his morning tea.

*Guided by your odor to the charming climate

I see a port fall of sails and masts

Still exhausted by the waves of the sea

Daring the perfume of the green tamarind trees

Which circles in the air and fills the nostrils

And mingles in my spirit with the songs of the sailors

(A rough literal translation. RC)

As Octave sat on a rock in his yard sipping the hot sweet tea and listening to the wind voices in the wind-bent filao trees, as was his habit in the early morning, an old man, his uncle Robert, came up the path. Robert fished at night with bamboo cages and now he was going home.

“Mofine, mofine,” mofine: bad luck ) the old man complained. He said he had only three pounds of fish to show for the night’s work. “Ena trop boucoup pechere, zotla rode posson partout – et poisson misere. C’est malheureux, mofine, mofine. Too many fishermen now, they hunt fish everywhere in the lagoon – the catch is miserable, It makes for unhappiness, bad luck, bad luck.

Octave’s voice was almost harsh. “Don’t say mofine,” he said, “Don’t speak like that, my uncle. It is the will of God.”

The old fishing village of Grand Gaube, founded by freed slaves of mixed African and French blood a century before, lay quiet and serene in its small cove on the northernmost extreme of the Indian Ocean island of Mauritius. Spreading inward from the shore toward the sugar cane fields were five little communities, Grand Gaube proper, Callasse, Roche Terre, Melville and Batie. Two paved roads, one following the seashore to Cap Malheureux: where the whites had their weekend beach homes and the other reaching island to the main highway to Fort Louie, the Mauritian capital and only harbor, met at right angles in the center of the village, so there was no through traffic. Here were the police station, post office, dispensary, “family planning” clinic, Roman Catholic church and primary school, a few small Chinese grocery stores and wine shops and a gracious park along the cove with its grove of filao trees where, in the afternoons, the fishermen sat mending their nets, building and repairing their wooden pirogues, weighing their catches, haggling with the Indian fish mongers and, for much of the time, just sitting, gossiping or playing rummy and gambling.

Extending in a semi-circle around the cove and up and down the two main roads and numerous little cobbled lanes were small one-story rock, concrete or wooden houses with small yards, a few trees or semi-tropical plans and sometimes a garden set behind low stone walls.

In the inland quarter of Roche Terre, at the junction of the main village street and the road to Port Louis, stood the house of Dhanilall Thug, or Prem as his friends called him. Prem was a Hindu student who had been unemployed for the past two years since he lacked money to continue his studies and could not find a job, even working as a laborer in the sugar cane fields like his father. Prem’s house, partly hidden by the over-hanging branches of native leela and mango trees, was tin-roofed and sided with cheap lumber and except for beds and a crude table, almost bare inside. It was typical of the dwellings of the island’s mostly Indian sugar cane workers; what extra money there was usually went for education. The Creole fishermen near the shore, in contrast, had much better houses. Usually a wide front porch, immaculate red-tiled floors, curtains and table-cloths, many framed pictures of their relatives, a large pink doll or two for decoration, and always a fresh batch of ferns or flowers on the table. Both the Creoles and Indians liked to paper their inside walls with magazine illustrations.

Prem’s father, who sold peanuts in Grand Gaube in the evening, and a brother who was earning money to pay for his apprenticeship as a tailor, had already left the house when Prem awoke. Two teenage brothers and a small sister were still sleeping. Two older sisters had married well and lived in Port Louis. Prem had stayed out of school for three years to work in the cane fields and help his father pay for their dowries. As the only educated member of his family, Prem had a small room of his own with a desk where he kept his old schoolbooks, letters, a stamp collection and seashells. On a peg hung his Boy Scout uniform; he was the chief commissioner for the northern half of the island. There were also his junior lifesaving certificates; he still went to practice every Sunday. Prem was proud of his books; he had a fall collection of Shakespeare’s plays and Milton’s poems. But he had not been in school for two years now and the rats had nibbled at the edges of some of the books.

This morning, like Octave, Prem rose and looked at the sky. Seeing the sky was cloudless except for a low black mass on the northern horizon, he too hurriedly scrambled into a pair of torn pants and a faded shirt. He went outside to the tap and splashed some cold water on his face, wiping it with a rag, and then carefully brushed his teeth. Unlike his father and mother and the younger children, Prem and his oldest brother used a brush and toothpaste. Then, with a goodbye to his mother, who was heating cakes to sell to the schoolchildren later in the morning, Prem took his breathing tube, mask and rubber fins and hurriedly started down the road to the cove.

For some weeks now, Prem had been going fishing every morning with Octave. Although long passing acquaintances, they had become friends two months before during the evenings when Prem, worrying about his future, had gone to sit and watch the sunset under the filao trees along the cove, Prem had been despairing and wanted to be alone to think. He did not know what to do, and after searching for every kind of job, had begun to think Shakespeare was right, life was a tale told by an idiot, full of sound and fury, signifying nothing.

Then one evening Octave told him two South African tourists had hired his pirogue for a week’s skin-diving. He wanted to know if Prem would come along as an interpreter since the South Africans did not understand Creole, the island’s French patois, and Octave knew little English, The week had been a fine adventure; one of the South, Africans had killed a shark and Prem had helped pull it into the pirogue. Then they had left, giving Prem a set of fins and a mask and he had continued to fish with Octave every day. If the catch was not good, Octave gave him one or two fish to take back to his family but sometimes, when they caught as much as twenty or thirty pounds of fish and octopus, Prem would get two or three rupees.*

The future of Prem’s family was precarious. His father was 56 and would be forcibly retired from the sugar plantation in four more years, meaning that the family’s earnings of 31 rupees a week would fall to a pension of a mere 20 rupees a month. Prem, at 22, had spent the past two years writing to seventy-six hospitals in England applying for a job either as an orderly or to enroll in nurse’s training, as many Mauritian youths had done in the past. If he could only get to England, Prem thought, he could save enough to send money home to finance the education of his two youngest brothers whom his father had taken out of school. Bat as time wore on his applications grew increasingly more desperate and the answers more curt. In a way it was a race against time. There was not only his father’s age to consider but there were now already 15,000 high school graduates without jobs and the number mounted by another 7,000 or so each year. Most of them were also trying to get to England.

Security and a happily ever after, in Prem’s mind, had come to take the form of acceptance by such imagined havens as St. Matthew’s Hospital in London, the Royal West Sussez Hospital of Chichester, Southend-on-Sea Hospital or Pontefract General Infirmary. But month by mouth, the negative replies came in. “I have my full quota of overseas students for some time ahead…I am sorry, so many Mauritian students have applied…I regret…I regret…unable to help you…your application has been unsuccessful…cannot consider…no vacancy…no vacancy….”

Finally, a letter came. Appearing, as it seemed to Prem, like a guardian angel, a Miss R. K. Ware, Principal Nursing Officer, Churchill Hospital, Oxford, England, wrote that he could be admitted for training as soon as the hospital secured a worker’s permit for him. But she warned this might take as much as three years. More months passed and then one day the Mauritian government announced it had tightened up its qualifications. Two passes on one’s high school certificate, as Prem had, were no longer enough; three were required. Dismayed, Prem went to the Labor Ministry. The officials told him that in his case the new requirements could be waived if the hospital matron in England agreed. A letter to her would be sent accordingly. The letter went to London bat for some reason was not forwarded by the Mauritian High Commission there. Prem wrote Miss Ware desperately, trying to explain what happened. Her reply was like a great steel door slamming on his hopes of emigration. “I am deeply sorry, Mr. Thug,” she wrote, “but as you have been turned down by your Government, I am unable to help you in any way.”

Unable to help you in any way. What would become of them, Prem wondered, himself, his family, the Mauritians? Fall of sound and fury, he kept repeating to himself those evenings by the cove, signifying nothing.

The quick flatter of morning birds brought Prem out of his reverie. The sugar cane scurried with waking life as he walked. The quiet thudding of his sandals in the dust, the squeak of mice and chirping of feeding birds, sounded against the other secret noises of the dawn. Sometimes an angry defiance rose up in Prem as if the frustration would well over, It reminded him of those words of Lucifer’s in Paradise Lost:

The mind is its own place

And can make a Heaven of Hell

A Hell of Heaven

Better to reign in Hell

Than serve in Heaven

Although a Hindu by birth – his mother prayed each morning to a little shrine of the monkey god, Hanuman, in their garden – Prem believed in the Biblical account of creation and Adam and Eve. He also half-believed there would be a Day of Judgment. One of his friends in the village, Andre, a Creole fisherman, maintained that the plight of Mauritius fulfilled the prophecies of Revelation.

“The Apocalypse is drawing near,” Andre told Prem one day. “Day after day, we see the people becoming more evil. There is a place in the book of Daniel where he says that in the last days and the last times before the ending of the world, God will fill all the people with intelligence. Before and after Daniel’s time until now this was not true, but we see it in this generation, in this time we live in. We are living at the point, Prem.” Prem thought Andre, who was as pale as a Frenchman, a little mad and yet he too felt a sense of apocalypse. In the village, the old men also spoke of it and said starvation was coming. Even three years ago a fisherman might take home a catch worth five rupees on an average day; now he was lucky to get two or three. And what would happen a year, two years, five years from now?

Only a week before a Hindu classmate of Prem’s at school had committed suicide. His parents, illiterate cane workers like Prem’s, could not understand why their son could not find a job after they had sacrificed for years for his education. They criticized him for laziness. One evening he went behind his house and hung himself.

Other youths were turning to a new revolutionary force called the Mouvement Militant Mauricien. Prem had attended an MMM rally in a neighboring village. Berenger, its leader, a white, had attacked the government for allowing famine, disease, prostitution, humiliation and exploitation among the people and called for a violent revolution to sweep all the capitalists aside. Prem had silently agreed with much of what Berenger said but he did not understand how the MMM would succeed any more than the present government in providing jobs for the people. Instead, he felt, violence might ruin the island’s economy and send it back to subsistence poverty and possibly starvation. Prem felt there had to be another way.

But the speech that disturbed him most was one by a young Hindu schoolteacher, Dev Virahsawmy, who said that “the present educational system, with its heavy emphasis on parrot learning produces masses of expensive illiterates who have been psychologically and mentally raped….There are those who argue that the present system prepares Mauritians for emigration. But anyone who has given the emigration question some attention will understand how facile and unrealistic, not to say tragic, such a stand is. Our educational system should prepare Mauritians to live decently in Mauritius.”

It is true, Prem thought. I was a fool to think everything could be solved if I could only get to England. He remembered something else the speaker had said, “Latin and Greek, Shakespeare and Milton are still taught in many schools while the knowledge of modern technology and agriculture and Mauritian history is practically non-existent; Mauritian students burn the midnight oil to learn by heart the Battle of Hastings.”

“September 29, 1066, at Semlac.” Prem automatically recalled, “The Norman victory led William the Conquerer to claim the English throne.” So much of what you learned by rote stuck in your mind. But he agreed that there should be more emphasis on technology and agriculture. But at the expense of the rest? For Prem loved English literature and found the poems and dramas a great solace in life, even though he sometimes misquoted his favorite passages. Perhaps his favorite was “Julius Caesar” and he often quoted to himself, “Why does he bestride the narrow world like a colossus? We petty men under his huge legs peek about to find ourselves dishonorable graves….”

What the MMM says is true, Prem said to himself. But what can they do? How are they going to solve the problem of unemployment when we have too many people in Mauritius. The speaker didn’t want people to emigrate. But has he enough jobs to give all the people?

At the end of the meeting, Prem had run into another youth from Grand Gaube, George, a Creole student and poet. George told him he had joined the MMM and said its real plan was to stage a revolt but not for five or six years or until the police and unions could be penetrated and organized. Prem noticed all the speakers and MMM officers had come in big new cars.

In the village too, one heard talk of revolt. Not from the fishermen or cane workers but in the gangs of government relief laborers who were building a road. All over the island the government supported 15,000 such laborers, paying them four rupees a day for three days’ work a week. The Hindu foreman of the gang in Grand Gaube often cursed the government leaders as “vampires” and “Ali Baba and his forty thieves.” He often spoke of the coming revolt, when the people would “walk on blood.” One day he told Prem, “Our blood has not yet become hot, but when it does the revolution will be bloody. Oar children have no bread, but the ministers and their deputies are eating gold and diamonds.” Prem wondered if the foreman was a secret MMM agitator

Prem harried his pace as he neared the cove. He could see George, a young Creole who had only been fishing for a year and served as Octave’s boatman, was already pushing the pirogue toward the shore where Octave and Karl were waiting with their diving gear, the mast, sail, harpoon guns, spears and a gaff. To Prem, as he harried along the beach, it seemed as it did every morning, as if he were entering another world. He found the Creole fishermen, inclined to be quiet, almost sullen on land, to be a happy, carefree lot once they were under sail. “Octave welcomes life as it comes,” Prem said to himself. Octave, a mason by profession, had turned to the sea only two years ago when most construction slowed down with the fall in the island’s economy. Now, unable to earn more than a rupee or two a day fishing with the nets, lines or cages the other fishermen used, Octave had struck out for himself in the more hazardous underwater fishing, using spears for octopus and a harpoon gun for large fish just inside or beyond the reef. Since there were sharks and barracuda in the waters, both inside the lagoon and beyond, few villagers would dive underwater. Indeed, there were some who could not swim. Almost every year, especially in the stormy seas of winter, a few villagers were drowned.

When Prem reached Octave and Karl they greeted each other with a nod and waded in silence oat to the pirogue. They loaded the mast, rigging, gaffs, spears and stowed the diving gear in the stern.

The pirogue was constructed of local bois noire wooden beams and planks imported from Singapore. Heavy rocks had been put in the bottom as ballast and a large rock tied to a rope served as an anchor. Octave climbed in and moved to the stem with a gaff to help George push the pirogue past the rocks and across the shallow water now that the tide was out. Karl and Prem waded alongside. Karl, a wiry but muscular man, was considered one of the toughest Creoles in the village. Me frequently got into fights when he drank too much ran and once had been jailed for two months for knifing another fisherman. But he was also one of the ablest divers in Grand Gaube and used to double his earnings from the sea by gambling in the afternoons and evenings. The fishermen all said Karl knew all the tricks of gambling but no one had ever caught him cheating. Yet he usually won.

After some minutes Prem and Karl climbed into the boat and Karl tied a single narrow-bladed oar to a wooden rowlock and began rowing at a steady even pace toward the reef. Octave shouted directions to George, pointing out into the lagoon. “We’ll be at Ile d’Amber by sunrise,” he said, lifting the heavy mast into its fitting. He put a worn stick into the rudder’s slot as a tiller and raised the sail.

The sail flapped loosely for a few seconds until it caught the breeze. George lay down the gaff, Karl stopped rowing and the pirogue skimmed through the water, the waves slapping gently at the bow. The eastern sky grew fairer and it was possible to see the outline of the church steeple and the thatched and tin-roofed hats along the shore. A flock of pigeons started from the rocks and flew around the cove and settled again, white pigeons with iridescent wings.

Near some rocks as they moved into the lagoon two Hindu youths were wading, hunting for crayfish. One had caught a small octopus and was beating it against a rock.

“Look, I’ll scare them,” said Octave. He shouted, “Hey, over there. What’s that couyonade? (couyonade: nonsense) Will you let that small octopus go? You will have trouble. Will you leave it alone?”

One of the Hindu youths, apparently afraid since it was illegal to kill baby octopus near the shore, turned on the other. “You are silly.” they could hear him whisper across the water. “You are hitting a tiny one. Let it alone. I’ll wait for you by the church.” The youth scrambled for the shore, the other one not far behind as Karl and Octave roared with laughter.

“Many Malabar fishermen, we make them go away,” said Karl.

(Malabar: a derogatory Creole word for a Mauritian of Indian decent)

That is not good,” Prem told him. “They were frightened.”

Karl cursed, “‘Shut up your liki. * You have not the right to be angry. You are not a Malabar coolie, You are a Creole.”

(liki: the female sexual organ; a common Creole swear word)

“Look at the light coming,” said George, “like silver.” A little color came into the eastern sky and almost at once the lonely dawn line crept toward the sea turning it from leaden grey to a misty dark green. Green appeared in the tree line on the shore and the earth, was gray brown. In the pirogue, the faces lost their grayish shine. Octave’s face, half-hidden under a shapeless slouch hat with a torn brim, seemed to darken with the growing light.

“This is a good time of the day,” Octave murmured, feeling wide-awake now that they were underway. “Will I get some fish with you, George? Will we catch fifty pounds today?”

“Non,” coughed George in a sleepy voice.

“I mast have twenty rupees for the New Year.” Octave said. “Now I have not one cent to buy my sweetheart a present.” Octave was engaged to be married to a girl in the nearby village of Poudre d’Or, but, as the others were aware, lacked enough money to pay for a wedding. A church wedding was expensive since Creole custom demanded the groom hire a hall and dance band in Port Louis for receptions that sometimes lasted until dawn and then there was the cost of furniture to consider. Octave planned to live in his father’s house in Grand Gaube, perhaps adding a room or two, which he would build himself.

“Not even one cent for the New Year, I have not,” grumbled Karl.

“We mast fish hard to have twenty rupees.” said Octave.

“Fishing? You, can make so much fishing? Non.” Karl grinned at Octave’s joke. Lately they had been bringing home catches of twenty to thirty pounds. This meant about twelve rupees in all with two going to the boat’s owner and the rest being split among the four of them. Karl grinned at Prem. “Hey, you are no Malabar. No coolie. You look like a Creole. You eat chicken, beef and pork. You can ask for the hand of Octave’s sister.”

Prem was embarrassed. Hindus did not joke about their sisters and he was fond of Lydia, Octave’s younger sister who was pretty and fair. “I don’t eat pork,” he told Karl.

Octave agreed. “No, he doesn’t eat pork, But if you ask for the hand of my sister, Prem, you must eat pork and rats. And if you come to court on Sunday you can stay all night, if it rains. And on Monday you and I shall go fishing together. You can sleep with my…..” Octave began to laugh at Prem’s embarrassment.

Indeed, compared with the Creole fisherman, Prem was almost a Victorian romantic. He considered it daring of the sophisticated Hindu girls from Port Louis who came to his Sunday life saving classes and made jokes of his shyness. He never told his parents about them for fear they would object. In the village, some of the Hindu marriages were still arranged by the parents and the bride and groom only met on their wedding day. Prem had never danced until Octave and Karl took him to a Creole ball. His ideas on love, as on many things, came from books. His favorite was Bernardin de St. Pierre’s Paul et Virginie, the tragic love story of a dark-skinned Creole and a French girl. Virginie is forced to leave Mauritius for France after an idyllic childhood romance with Paul. She returns, unable to stay away, only to be shipwrecked near Cap Malheureux and washed ashore, drowned, at Paul’s feet. Prem never tired of reading over Virginie’s final farewell to Paul as she is about to leave for France. “Maintenant je reste, je pars, je vis, je meurs; fais de moi ce que tu veux. Fille sans vertu! J’ai pu resister &agave; tes caresses, et je ne puis soutenir ta doleur!”

Karl broke Prem’s train of thought. “You know the girls here don’t like fishermen. You must tell them you only go fishing for fun.”

Octave started to sing, in mock-romantic style, “La coeur guerira la blessure, parlez moi d’amour….”

**Warming up, he switched to “Oh, Capri, c’est fini” improvising lyrics as he went along.

Dance with me

Don’t hold me so tight

We will fall down

And the others will laugh

She is called Gabriel

She is beautiful

She doesn’t give her love

I am a hippie at heart

I understand joking

I’m sentimental

I take life seriously

“There is a woman in Beau Bassin,” began Karl, “who is called Belinda. She has a beautiful liki. I met her at the ball last Saturday in Tamarin. I got into a fight. There’s some bad ones there in Tamarin. All because I boasted of Grand Gaube.” **”The heart will cure the wound, speak to me of love.”

* (Freely translated: “Now I stay, I go, I leave, I die; do with me what you will. A girl without virtue. I can resist your caresses but not your suffering!”)

Octave asked. “Is she a little woman, the one you flirted with?”

Karl went on, “I made her younger sister too. At the dance. But I had no taste to sleep with them, these city girls from Beau Bassin. The older one got mad. I guess I was a little drunk.”

Octave said, “If I had been with you, we could have passed along that same road together.”‘

Karl: “Her little sister sat on my lap and I squeezed her breasts. I told her I most sleep with you. I asked her, what do you want? A necklace? A Coca Cola? But I must have you.

Octave: “If she was hot enough, who could have stopped her?” He shouted back to George, who was now holding the rudder, “Hey, gogot,*put the rudder to the outside.” He looked around at the water. “Little Arnaud said he saw a barracuda around here.”

(gogot: the male sexual organ. The Creole fisherman’s conversation at sea, although not at home or in mixed company, is filled with pungent expressions. Since they do not lend themselves to translation, I am left such words in the patois in the text.)

Octave began to sing again:

Non rien de rien

Je ne regrette rien

Non rien de rien

Je ne regrette rien

Dont to avait baleye les amoureux

Octave is singing a parody of Edith Piaf’s most memorable ballad

Karl said, “When you go to Tamarin, you must have a firm friend with you. Those people are tough and proud.”

“Like me.” said Octave.

“Four times truth, forty times lies,” Karl said, quoting a village saying. “She was much older than me,” he admitted.

“Not much.” laughed Octave. “Only forty-five. Two elderly sisters and Karl.” He began to laugh again and said, “Perhaps the two of them were whores.” He sang:

Little woman

The gallants promise you

Then run away

But don’t hug me too tight

I am fragile

You’ll make me afraid

“Buffoon.” snarled Karl. “Liki of your mama.” After a minute he added, “The woman of Beau Bassin wrote me a letter.”

“Will you go to Tamarin again?” asked Octave.

Karl shrugged. “To hell with her. There is not one taste to them, the women of Beau Bassin.”

Octave sang another chorus of “Je ne regrette rien.” A redness grew up out of the eastern horizon, catching with pink and silver light the small patches of broken white in the choppy water. Smoke rose from the chimney of an island sugar factory and Octave could now see the green slopes rising to the high plateau, all planted in sugar cane and beyond, blue hazy hills all still and far, far distant the strange volcanic peaks: the Moka Range, Corps de Garde and, pointing like a rocky finger to the sky, Pieter Both, named after the Dutchman who reached the top and then fell to his death two centuries before.

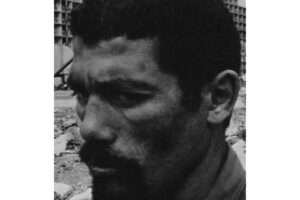

Octave took off his shapeless hat and mopped his face with it. His shorts and tricot were in rags, eaten away by the salt, sun, wind and rain. The sleeves of the worn tricot were tight on his arms, held down by bulging powerful muscles. Stomach and hips were lean and his legs, short, heavy and strong. His face was weathered a deep brown and his eyes, as they searched the water, were very bright blue and piercing, and wrinkled in the corners from squinting in the son. Thick black early hair framed a face that was both Gallic and African and neither: savage, humorous, wise, gentle, the face of the Mauritian Creole. There were strong deep lines cut from his cheeks in curves beside the mouth and it was when he laughed, as he did often showing his fine white teeth, that he looked as young as he was. His hands were hard, with broad fingers and nails as thick and ridged as little clam shells. The space between thumb and forefinger and the hams of his hands were shiny with callus. His feet bore small cats from the coral, as did Karl’s and Prem’s and because they spent hours each day in the salt water, they festered and took a long time to heal.

Prem asked Karl what he put on the cuts.

“The only good thing is to masturbate and rub the sperm in. Rub it well. It’s a good medicine.”

Prem, as frequently happened, could not tell if the fishermen were serious or not. Octave was singing again, this time to the melody of “Island in the Sun.”

Oh mon Ile au soleil

Paradie entre terre ciel

Ou le flot le long du jour

Change au sable fin chanson d’amour*

*Oh, island in the sun

Paradise between earth and sky

Where the boats in the daytime

Sing by the soft sand songs of love

“George was masturbating this morning.” Karl announced with a grin. “I saw him waiting on the road and the headlights of a car came behind him and the light caught his hand. I saw something shining and I said, ‘George, do you wear such a big ring?’ ‘Non.’ says George, ‘I don’t wear a ring.’ ‘Then why is your finger glittering?” George wiped his hand on his shirt but I saw it in the headlights of that car.” Karl laughed. “The hell with you, George. The hell with you. You were masturbating.”

George protested, “Non, non, I was not.”

Prem felt angry. “Don’t speak like that, Karl.”

Octave stopped singing. “Shut up your liki, Karl. George, spit.” George tried to spit but his mouth was dry. “George, don’t lie. You masturbated.” As Octave and Karl roared with laughter, George, to Prem’s surprise, mumbled, “Well, only men do it,” making the two fishermen laugh more.

Octave was in high spirits now. At the top of his lungs he sang from the bow to the tune of “Never On A Sunday.”

On voit des gris sous le ciel bleu

Un bateau deux bateaux trois bateaux

S’ent vont chantant

Dans le real on coup de siecle

Un oiseau, deux oiseaux, trois oiseaux

Font du beau temp*

“Oh. Bon Dieu, oh, mo mama, will I get fish with you today, George,” Octave grinned. “Will I have to tell you everything, always.”

They were approaching the reef and now there were outcroppings of “n…..”heads and meadows of sea grass and the watery roar of the sea beating against the reef masses of broken coral and sand. They had passed over the deeper channel of the lagoon and now entered the shallower waters of a shoal. As they drew near the reef and as the blinding san came over the horizon and fell on the pirogue, they sailed alongside a little fleet of five pirogues moving into the tossing waves, and splashing their gaffs on the water, hissing and beating batagesticks against the hulls to frighten fish into their large net, which flashed with beaded light in the spray. And the sun fell on their sail. The weathered canvas was gold and bright and they felt the sudden warmth of the sun. The white foam of the surf glittered with reflected light.

*We see some gray in the blue sky

One boat, two boats, three boats

Go singing

In the real the blow of the century

One bird two birds three birds

Make the weather good

(Octave, of coarse, improvised lyrics when he did not know the words, in a mixture of French and the Creole patois)

“Alle degage!” they heard the patron of the net fishermen shout. The two net boats moved together and the three gaff men in the batage boats shoved the craft faster and faster over the rocks. A roar of shouts and curses went up as the five boats bumped together and the heavy dripping net was hauled in.

“Pull hard!”

“Swing around!”

“Turn, turn!”

“Draw it in. Faster, faster.”

“Let the plomb go. Take the oars. Hold it fast.”

“Change your wine, François. That Bordeaux is too strong for you.”

“Quickly, Pa, quickly. Pull it in.”

“No, not that way, Herve. I’ll kill you. You are good for nothing but whoring and stealing.”

“Liki to mama, go fix the net.”

“Pull your boat in line, Pa.”

“Rolland, you gogot, barricade them with the net.”

“Hurry, hurry, ah, mo mama, ah, Bon Dieu, mo mama.”

Before striking out on his own, Octave had worked for some months with the net fishermen and he had liked the excitement of maneuvering the boats to catch shoals of fish and tossing the nets in the heavy surf. But there had been too many days of having to share a catch of twenty pounds among fifteen or sixteen men. A man could starve on that.

Octave watched as the boats moved apart again and the fishermen unfurled their sails. In each boat a lone man was standing in the bow with his gaff, turning the pirogues into the wind. He was silhouetted back against the sunrise and each boat, as the gaff man lifted his long wooden staff and splashed the water, seemed to have wings of bright golden spray. Beyond them and outside the reef were three large double-sailed boats with ten-man crews. They were thirty-two feet long, almost twice the size of the ordinary fisherman’s eighteen-foot pirogue, and with motors could take the heavy waves and go to the three offshore islands, L’Ile Platte, L’Ile Ronde and the fortress-shaped Coin de Mire and even twenty miles outside the reef where the currents would carry a pirogue oat to sea. Such a larger boat, called a peniche, brought home a big haul of fish every day. The three were owned by prosperous proprietors in the village.

Grand Gaube was the largest fishing village in Mauritius. Its 600 fishermen accounted for one-sixth of all those registered on the island, although about twice as many more men fished part time to feed their families until they found work. The fishermen of Grand Gaube had long sought the government’s help in getting large enough boats to go outside the reef bat in the past two years they had not been successful. Two months before an American fisheries expert had been sent by the United Nations to Mauritius. But his assignment turned out to be conducting a 5,000,000 rupee investigation of deep sea fishing, which, if it benefited anyone, would help the big, largely white commercial operators in Fort Louis. But the village council had still invited him to Grand Gaube and one day the American arrived-and met for an hour with the fishermen in the Roman Catholic primary school. The schoolroom was packed; more than two hundred fishermen came. Prem acted as interpreter and he soon saw the American, not understanding Creole or the fishermen’s rough manner, was somewhat frightened. He too became ill at ease when several fishermen shouted that they had been bluffed too many times in the past and no longer trusted the government. When the American said any help would have to go through the government, some of the fishermen stomped out and did not return. But others were more reasonable. The American said the important thing was to get the fishermen offshore and out of the depleted lagoon. He said if they choose leaders among themselves and formed an association of at least a hundred men, he would see what he could do about helping them to get bigger boats.

At the end of the meeting, the American promised to come back in two weeks. When a month went by and he did not return, Prem, and Octave went along with three of the older fishermen, patrons of net cooperatives, to see the American at his office in the Agricultural Ministry some twenty miles away on the other side of the island. They hired an old taxi and the fishermen all wore suits and ties and slicked down their hair as if they were going to church.

The American seemed friendly, surprised to see them. He said he had taken up the matter of bigger boats with the government and had been informed a fishing association already existed in Grand Gaube, part of a Catholic-sponsored organization with branches in nineteen villages around the coast. The fishermen knew of it. It was headed by a carpenter, one of the three men in Grand Gaube who owned a large boat. He charged a rupee’s membership fee and twenty-five cents a month. Less than thirty fishermen had joined. The others objected to the fee. What was the money to be used for? Moreover, the Catholic priests who led the organization in Port Louis seemed chiefly concerned with getting the fishermen to inform on anyone who used illegal dynamite or mosquito nets in the lagoon at night.

Octave tried to explain. “It’s just to make fishermen catch fishermen. To create hostility among friends. We are only poor fishermen….” Prem translated and the American replied,, “All fishermen are poor the world over.”

The American went on, “If you do not like the existing organization, it is up to the fishermen to change its character. It is already legally registered and the government wants as to work through it. Now I have also contacted the American Embassy for help. I think I have a fairly firm promise of help. They have agreed to give the necessary materials. But the boats must be built in the villages by the fishermen themselves. We call this ‘self-help.’ The fishermen must contribute their labor.”

Prem translated his words, knowing what the answer would be. In the village the boat builders or marine carpenters were not fishermen. It was a completely separate thing. And how could the fishermen on one or two rupees a day pay the marine carpenters to build boats for them. Hadn’t the American been to a fishing village on the island to see how it worked? The fishermen explained the situation but the American was adamant. “It has to be self-help,” he said. “The fishermen must contribute something. Otherwise they will not take care of the bigger boats. We have a lot of experience in this. They must contribute something.

The fishermen said the boats they needed would cost 20,000 rupees each and ten would be enough for Grand Gaube. Multiply this by six, Prem thought, and with 1,200,000 rupees you could change the whole fishing economy. And yet the government and United Nations were spending four times that just for an investigation of commercial deep sea fishing that might not benefit the people for years. And they didn’t have years. Not in Grand Gaube. Fishing was, aside from working on the docks of Fort Louis, the main occupation of the Creoles.

Prem tried to pat this into words and was surprised to hear the edge of anger in his own voice. The American started to sound impatient.

“Tell them there are just too many fishermen. There are not enough fish in the lagoon. I know fishermen have many problems and I sympathize with them. But speaking frankly, there are too many fishermen and there aren’t enough fish in the lagoon. Also, I should remind you I am here on a project requested by the government. The government has not asked for help for the lagoon fishermen. There are too many. They have got to find something else to do.”

But what? Prem was reminded of Hindu schoolteacher at the MMM meeting, saying the educational system should be changed to prepare Mauritians to live decent lives in Mauritius, How then did he propose to get everyone jobs? He also thought of Miss Ware: I am deeply sorry, Mr. Thug, bat as you have been turned down by your government, I am unable to help you in any way.

“There are too many fishermen. There are not enough fish in the lagoon….” the American kept repeating. Should Prem keep on translating he wondered. The fishermen knew that before they came. That was why they had come. And then an American woman had come in the door, excused herself, gestured to her watch to her husband and gone outside. The American said he was sorry but he was already late for another engagement. He shook hands with the fishermen and Prem but said nothing about a third meeting.

There was little conversation in the taxi until they drove through the outskirts of Port Louis. Then Octave said, “You had a hot discussion, Prem.” After a pause, he went on, “We are exhausted. To be relieved, we must have a bit of rum.” All agreed and they stopped at a cheap open-air rum shop along the harbor, Prem took only a glass of beer but the fishermen, after a double peg of rum, became animated once more and ordered a third round. Walking back to the taxi, Octave pat his arm around Prem’s shoulder. “You are like a brother to me, Prem. I am very, very unhappy when I look to the future. I am saving every rupee now to get married but I do not know what will happen when winter comes. Sometimes it is so cold in the water I want to cry out.” Octave stumbled on the curb; the rum had made him groggy. He straightened up and told Prem, “I do not live for money. I live for dignity.”

Now there was no more talk of the American or of bigger boats and Prem wondered to himself what would happen to Grand Gaube. If the fishermen could have the right boats and training, he thought, they could have a good life. If they could only organize. If they do not, they will never have anything. But there is no real hope for them, they have been promised so many times before. And somehow they no longer seem to have the spirit to get together and fight for what they must have. In the next two, three, four years what will happen? There will be many fishermen, less fish and some may starve.

Their life is hard. If you’re at sea you can get drowned at any time. Some days you catch nothing. And if you get nothing, what shall you eat? It will always be hard for the fishermen. And they are extravagant. At a Creole ball in the village, Prem had seen a woman with no shoes pay three rupees for a ticket to go and dance all night. A Hindu would have bought a pair of sandals instead, he felt. Also, the fishermen got into fist fights and kicking matches after they had drunk much at the balls. Yet they went to church the next morning . Sometimes Prem felt he would never understand them.

“Hey, Cokol!” Karl shouted at a passing pirogue, bringing Prem back to the present. “Cokol is the premier buffoon of Grand Gaube,” Karl told him. “One day he told his wife he was ill. At that time his wife was pregnant and he took one of her pills. He was sick for a week. One time his wife bought a big milk can. He used it for a Sega (Sega: the Mauritian variant of the calypso ) drum and it cracked up the side. Once he spent ten rupees on ram and then started to weep about it, the liki of his mother.”

Octave laughed. “He is a real couyon,(couyon: a foolish man) that one. Once Cokol was cutting his nails with a hedge cutter. His nails were so hard the edge became blunt.”

“Once he was cutting his hair and he drew an unbreakable comb through it and it split three ways,” said Karl.

“Cokol stepped on a laff (laff: a poison fish) but when he took his foot away the laff was already dead. You or I would have gone to sleep in the hospital.” Octave shifted the sail into the wind and everyone ducked his head as it swung around and the pirogue changed direction, moving parallel with the reef. Octave was impatient to start fishing. He said, “The boat is as slow today as a morpion (Morpion: the tiny crab-like flea transmitted in sexual intercourse) at the funeral of a femme petain.” (Femme petain: a prostitute)

Shafts of sunlight pierced the shallow green water beside them and the light made prisms above the pink, green, yellow and lavender coral. The boat entered deeper water, the green and brown and white of the deep shoal. Below, sand stretched emptily in the mist between little islands of coral and there was not a living thing in sight. They were near l’Ile d’Ambre now, a deserted sandy mound of tall grasses and filao trees.

“Where are we going?” asked George.

“On your mother.” Octave replied. He turned the tiller to the side, pointing the pirogue directly into turbulent break in the reef leading to the open sea. Barracuda Pass, a turbulent break in the reef leading to the open sea.

The milky green water became rougher than in the enclosed lagoon and it turned blue-black where the ram-part fell, sliff-like, a hundred fathoms into the sea. The boat started to toss gently in the slow swells and choppy waves. Octave stood in the stern, watching the sea. Dark gray clouds were beginning to form on the northern horizon. But toward the island the billowing white cumulus looked friendly and only the thin feathers of cirrus clouds were overhead.

“Push, push, George, take the gaff. Karl, pull the rigging. We shall work through the pass toward the rampart.” Octave stripped down to his swimming trunks and settled against the boat’s wooden edge. He squinted judiciously at the water, dipping in his fins to make them wet and slippery. “Wake up, Prem. Hand me the spear gun. You kill me, George. Can you reach the bottom with the gaff here? If not, use the oar. Will you give me a heart attack, George? The roughness of the water is determined by the size of the waves. You are a pubic hair, George. You are like a gogot. Rest a moment. The current itself is moving the pirogue.”

George sat down on the wooden edge and watched Octave rethread the line of his harpoon gun. Prem. was robbing spit on the inside of his visor to prevent it from clouding up underwater. Octave and Karl had already donned their fins and masks and flopped backward into the water when he finished. Once the two fishermen were swimming away from the boat, George told Prem, “Octave takes me to be stupid. He believes that I don’t know how to hold the boat. But how would he manage if I had not come?” Prem knew this to be true. Octave was dependent on the skill of George, whom he had taught to use the gaff and sail. He also knew George loved Octave like a father and trusted Octave’s profound knowledge of the sea completely.

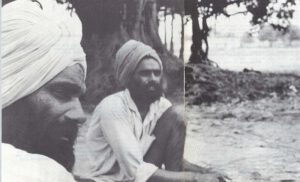

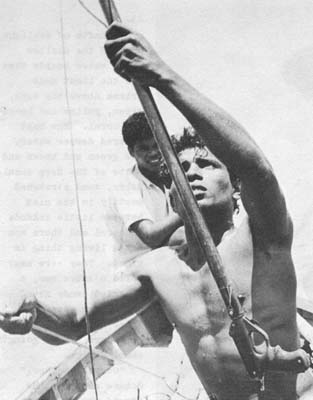

The George and Octave

Karl

Prem

George, after his silence in front of Octave and Karl, now grew talkative and he told Prem about an experience he had had the evening before. There was a girl in the village who had no boyfriend, gallant was George’s word, and he had approached her and said, “Where are you going, ma jolie? You will get lost in the wind.” But instead of replying in the same vein, as the heroines of George’s romans d’amourdid, the girl cursed him, “Liki to mama,” and ran away.

Prem stifled a laugh; George had come to confide in him lately. George said he wanted to tell Prem about a troubling dream he had had in the night. “You know what it was about? I have loved a girl. Her father caught us when we were together. He dragged the girl away to their house. The girl slipped away and said to me, “I’ll stay with you.” When I told her I had nine younger brothers and could not keep a woman like her in my house, she doesn’t care. But my father too finds out and he wants to push me out of the house. My mother speaks to my father and he finally agrees to our marriage. This time my wife gets a job in the house of a blanc.* We have got some rooms to live in at the same house of the blanc. I have left my mother and father and gone there to live. Then one day I find the blanc with my wife. I was so afraid and mad I woke up then and was shaking.”

“Do you really know the girl?”

“Yes, I met her but she doesn’t live in Grand Gaube.”

Just then Karl swam up to the pirogue and dropped a red parrot fish over the side. He held on the side for a moment, getting his breath, and when he saw Prem and George conversing, grinned, “There’s a lot of old women sitting around the boat today.”

Prem dipped his fins over the side of the boat, spat on the inside of the visor again and dropped backward into the water to avoid splashing George. He swam away from the boat toward Octave, moving slowly forward, his fins pulsing softly just below the surface so as to make no sound. He looked around him through the glass visor, trying to pierce the misty horizons of Barracuda Pass. To his left, the coral reef fell sharply and perhaps fifteen or twenty feet below there was a flat shelf, scattered with black rocks, open stretches of white sand and clumps of posidonia, the common seaweed of all oceans. Unlike the choppy surface of the pass, the sea was calm below, almost sluggish. The great coral reef of l’Ile d’Ambre was varied: each pass had a distinct appearance: Kalodin was light and shallow; Ramzan full of caves and tunnels: Basmaurice like a small sunken island under the sea. Prem liked Troualbert best. It was named after Albert Hall in London and was a break in the coral shaped underwater like a giant amphitheater or a cathedral. Prem always half-expected to hear a chorale of sea spirits from its silent, misty green depths. But the surface water at Troualbert was too turbulent except on all but the calmest days; George could not hold the boat in the deep water and there was a danger it would smash against the reef.

*blanc: a derogatory word used by the Creoles to describe a white Mauritian of French descent; the former slave owner class, It does not apply to other Europeans or whites in general.

Prem saw Octave’s blue fins ahead and the luminescent air bubbles they left in their wake. The fisherman paused, floating on the surface, and then dove to the floor of the sandy shelf, investigating a few promising rocks thick with weed. Prem watched Octave tense as he found a two-pound spiny-backed Cordonier fish, a fish of the premier class that fetched a rupee a pound, which was nibbling algae from a lump of coral. Octave held his heavy blue Champion harpoon gun before him and moved slowly toward the fish, his body flat in the water like an infantryman edging himself forward across a battlefield. The harpoon was tipped with a needle-sharp trident – a short-range weapon of perhaps ten to twelve feet of killing power bat best for reef fishing. In the air, it was said, the harpoon could pierce the bodies of three men.

Prem swam to just above Octave; he never dove down beside him until Octave pulled the trigger for fear of disturbing the fish. When he heard the sharp ping as the harpoon was released, Prem surface dived. Then he remembered to cast a glance around him to see if there was any big larking shape. There was always a danger, once Octave and Karl began to dive, that a shark or barracuda would witness a kill and that the blood of the harpoon’s wound might bring scavengers from the deep water. But there was nothing in sight. Prem saw a pink parrot fish, watching without fear but curious, as the Cordonier lashed its tail in reflex aggression. Prem broke the surface to beckon to George, who had drifted fifty feet away, to push the pirogue their direction and Octave swam toward it quickly, holding the fish in his hand to show George and then dropping it over the side of the boat. Octave held on to the boat for a moment and then swam back again. H-e beckoned to Prem to follow him closely this time.

As they dove deep into the water together, exploring the eaves and hiding places along the face of the rampart, a dense mass of silvery brette fish, glinting blue and yellow in the shafts of sunlight, showed up ahead. Below, near the sandy greenish floor of the elf, was another shoal of larger black fish. As they dove after them, the mass divided sharply, leaving a wide channel and then closed behind them in a single black cloud. Prem and Octave swam softly forward. A carpet of sea-grass began and then a patch of broken coral and a large “n…..”head. They stopped and floated, their eyes scanning the brilliant jungle. A blue green materialized through the far mist and came toward them, a beautiful Cato Verte fish. It circled closely below them as if showing itself off and its dark blue eyes examined them without fear. The large fish busied itself with some algae on the underside of a coral rock and Octave moved toward it, slowly raising his spear gun. Just as he aimed and pulled the trigger the fish made a dart at a speck of something suspended in the water and Octave had to reload the gun, paddling almost vertically in the water. But the Cato Verte circled back as if to once more show off its beauty and Octave fired a second time, piercing the fish in the head with his harpoon. Once he heard it fire, Prem looked around in preparation to dive. The rampart, he observed here, fell very steeply into deep water and it was impossible to see very far in the green mist. Then his body tensed and his head swiveled sharply to the right. Some secret sense had instinctively warned him of danger and now he saw the larking black shadow, probably attracted by the thrashing of the Cato Verte.

At first Prem thought it was a shark. One had crept to within four feet of him one time and when he had seen it his stomach had crawled with fear and he had swam quietly but quickly to the boat. He had had only one good look at its wide, flattened, shovel-pointed head and the white-tipped pectoral fins. It had looked obscene and evil, a hateful scavenger of the sea and afterward he shivered when he thought of it. It had been almost six-feet long although everything looked larger in the water.

But this was not a shark. Its back was as blue as a swordfish and the belly was silver. It was longer than the shark was, Prem thought, but he found he was watching it with more awe than fear. It was slowly slicing its giant erect tail through the water but otherwise did not move. To Prem it seemed majestic and dignified. This fierce fish was very, very beautiful. His skin tightened but he kept swimming toward Octave in the same gentle rhythm. Then he saw it was moving on, ignoring them for some other prey beyond in the misty moving sea grass. Octave had also seen the big fish now and was swimming toward the boat, dragging the Cata Verte behind him on the harpoon line. When the fish was safely inside the pirogue, Octave shouted at Prem, “Barracuda! There’s a barracuda here. Follow me, Prem. Stay with me when I shoot a fish. Perhaps he’ll go away.” He told George to try and keep the boat within thirty feet of them and pulled his visor back on.

Almost at once, on the first dive, Octave harpooned a parrot fish and started swimming back to the pirogue. Prem, swimming by his side, again saw the big barracuda first. He reached out and hit Octave’s shoulder. The big fish was moving in behind Octave. Octave spun around and froze in the water, slowly pivoting his body until he was completely face to face with the barracuda, separated by only twenty feet of water. Slowly, Octave began to restring his harpoon gun. Prem stayed as close as he could to Octave’s side. For some seconds the three of them, the two men and the fish, hung suspended in the water. Then Karl came into view oat of the mist, called by George from the boat, and pointing his harpoon gun at the barracuda. Slowly, with Karl behind them, never turning his back to the big fish, Octave and Prem swam back to the boat. They lifted themselves over the edge. Karl stayed in the water for some moments, holding onto the pirogue but watching the barracuda until it vanished once more in the mist.

“Let’s go, Karl,” Octave shouted. “We can’t fish here with the barracuda around.” He told George to put the mast up. Water dripped from his body and he sat hunched, quivering with the cold and a delayed nervous reaction. “George, give me my tricot and my cigarettes.” From the pocket of his grimy tricot Octave brought oat a half-packet of cheap Embassy cigarettes. He passed one along to Karl and George and pat a third between his knees and bent to light it, where the wind could not get at it. Inhaling and wrapping the tricot around his shoulders, Octave felt instantly better and laughed, “Shall we have carry tonight? If you don’t eat fish, you shall eat greens.” He offered Karl, also huddling with cold, a cigarette and then started across the water at the shimmering sea and air. The clouds along the northern horizon were getting darker, almost a dark blue in places.

“George,” Octave said, “set sail, we will go to Roche Blanch to hunt octopus nearer the village. I don’t like that sky. Maybe a storm is coming.”

“Thunder is good for octopus,” said Karl. “They look out from their rocks. The most beautiful sea is today.”

George lifted the mast, struggling under its weight to put it in place. He lost his balance for a moment and the unfurled sail dipped into the water.

“George, to pena ene la vie?” Octave called. “Have you no life in you?”

“George masturbates too much,” grinned Karl.

“George is very slack today.” Octave went on. Eh, George, how can you make your living from net fishing? And you want me to take you outside the reef!”

Flustered, George forgot to pull up the rock, which served as an anchor before unfurling the sail. He had dropped it into the water during the excitement over the barracuda. Now Karl and Octave laughed at him. “What kind of fisherman puts up the sail without pulling up anchor?”

The sail caught the wind and the pirogue moved swiftly in the water as the wind was rising. Octave began telling George about the barracuda: “Six feet long, it was a lichien tazar.* Its mouth is very big. When it sees you it follows you, moving its tail right and left. It came and looked at me right in my mask and opened its jaws twice. Now why did it do that?” Octave shuddered, imitating the fish snapping its jaws. “When you shoot a fish the blood gets scattered in the water. A barracuda comes. If you have a fish it can hurt you, the liki of its mother beast. It was only twenty feet away, opening and shutting its mouth, maybe only five feet away from Karl. As you move toward it, it moves back. Very, very clever and treacherous. If you shoot a shark with the harpoon it will go away. A barracuda has a grudge. He will always try and fight you. A big head, the liki of its mother. When you get cut by coral and blood is coming out, it will attack you.”

“Barracuda,” Karl chuckled and smoked his cigarette with pleasure.

The pirogue passed another boat now, at anchor with its sail furled. A lone fisherman was casting lines into the water.

“Hey, Nicole,” shouted Octave. “I don’t waste my time with little fish like you do.”

“I fish little by little,” the man called back.

“I fish once and in great quantity.” retorted Octave, holding up the Cordonier for the man to see.

*lichien tazar: dog barracuda

The man called back, “Watch out or I’ll shove it up your liki.”

Then the other boat was out of earshot, George held up the harpoon gun and threatened it, “I’ll shoot you like a dog.”

“George, you are a savage,” laughed Octave. “You are a black comic. Now where are you going? Roche Blanch is not outside the reef, it is inside. We’ll go outside the reef on a calm day. With those black clouds spreading it is dangerous.”

The northern sky was a very dark blue over the three small offshore islands: Ile Ronde, Ile Platte and Coin de Mire. “It’s good to fish in the early morning.” George ventured. “One has the appetite to work.”

They were nearer the reef again and the roar of crashing waves came closer.

“Where are you going, George?”

“To the shallow place for octopus.” George leaned forward, examining the bottom of one foot.

“George stepped on a sea urchin yesterday.” Karl volunteered.

If you are lucky, George,” said Octave. “But you take me for a couyon when you say this is Roche Blanch. I think you will never succeed in bringing me to Roche Blanch. But we can fish here. At any time there is plenty of octopus in this place. Put down the sail.”

The water was very choppy now and Prem looked at the gathering storm clouds with apprehension. Spray splashed into the boat and once a sudden, unexpected wave came into the boat itself, drenching their backs and sending all four into laughter.

“The octopus come in from outside the reef here, not one by one but three or four hundred at once. En gloc. In a single mass that spills over the reef and then separates.”

“Did you ever see it happen, Octave?”

“Non, I heard about it.”

“Once when I was net fishing with Bally an octopus grabbed me around the chest. I was wading on the reef,” said George. “We were polling in the net and the octopus came and walked on me. I was afraid. Bally shouted to dive into the water so the octopus could relax and bite its head. I was afraid but I bit it and it let go.”

“George, you are couyon,” said Karl. “George is the premier buffoon of Grand Gaube.”

“The octopus is very, very clever,” said Octave.

“If it has seen an eel, it will send out one tentacle and when the eel will come to eat it, it will send another to hook it and pull the eel back into its hole.”

Octave began to sing as he got ready to dive again, this time with a larfine*instead of the harpoon gun.

He stood up in the bow with his back turned on the others.

Her husband is a fisherman

Catching small fish

And when the sea rises

And the line breaks

She will find another husband

“You piss in the sea, you, Octave?” George scolded.

“Where do you want me to go?”

“Is the bank here, Octave?” George pointed to a steep fall of rocks under the water.

“Oui. Pull the boat forward. Can you hold the boat?” The waves were heavier now.

“Do you want me to follow you with the boat?”

“Oui.” Octave, Karl and Prem slipped into their gear and dropped into the cold water once more. The floor of the lagoon was brilliant here with open stretches of sand and yellow seaweed. Here and there were little islands of coral, with the blue and green feelers of langoustes waving from their crevices. There were schools of tiny little golden fish and the beautiful splayed fingers of a Venus harp. The water was a very pale green, almost clear. But these things were commonplace to the fishermen and they paddled the fins steadily on, interested in the coral formations only as cover through which they could catch a glimpse of an octopus head and eyes. Octave did not have long to wait. A small octopus under a flat rock, feeling the man’s shockwaves, turned from dark brown to pale gray and squeezed itself softly into the dark crevice of the rocks that were its home. But too late. Octave’s barbed larfine cut through the water and pinned the octopus to the coral. Octave plunged the point in and out as a cloud of brown ink spread through the water. Still the creature lived on, its tentacles clutching at Octave’s arm, as he ripped it off the larfine (larfine: a five-foot wooden spear with a barbed steel hook at the tip) and carried it back to the boat in his hand.

George took it from Octave and beat the squirming head with the tiller stick until the tentacles stopped clutching at him and relaxed and the octopus was dead.

The wind had become stronger and rumbles of thunder could be heard from the north. The whole northern horizon above the white edge of the reef was a dark purple now although it was not yet noon and George felt afraid. Still he was reassured by the presence of a dozen or more other pirogues visible in the lagoon. George struggled with the gaff to hold the boat in place, but the waves kept beating it closer and closer to the reef and farther away from the swimmers. Once Octave’s head broke the surface and ripping off his mask he shouted at George, “Don’t go on that bank. Drop the anchor. Stay oat in the deep water. It’s dangerous near the reef.”

George threw in the anchor. But the waves still seemed to be dragging the boat toward the reef and he thought of tying a heavier rock to the anchor rope but he was afraid to put down the gaff. Octave swam up to the boat, dropped another octopus over the side and vanished into the water. Karl brought two more and then, when Octave brought his fourth or fifth octopus, he stopped and climbed into the boat, shivering with the cold. Octave wrapped the wet sail around his shoulders and squatted in the bottom of the boat. Prem and Karl were still in the water and he shouted at them to return.

“You can get knocked over by the waves today. George, to hold a boat, you cannot.” Octave pulled oat his pack of cigarettes and studied it slowly. He took out the last remaining cigarette, lighted it and threw the burning match into the sea. “A scarcity of cigarettes,” he said. He went back to the stern and sat by the tiller stick. “Later you are going to die, George,” he said. “We all are.” Octave stared north at the black sky and the green waves toward the reef. “The darkness is spreading everywhere, mo mama. This eastern wind makes the sea agitated. If the weather was really bad though all those boats would turn back to the village.”

“The wind has changed, Octave.” George said. “It is blowing from the north now.”

Octave’s eyes rested darkly on the sky and then on the small pile of octopus in the bottom of the boat. He reached down and ripped the slimy tentacle of an octopus away from the beautiful blue-green scales of the dead Cato Verte. “So the hoar demands that we go home.”

Octave was about to call the others when Karl’s voice rose from the water. “Octave, come! The gaff! A big octopus!”

“Don’t touch it, frere.” Octave called, grabbing his fine and visor. “Don’t disturb it, frere.” George watched as Octave joined Karl and Prem and they fought the octopus underwater, the tips of their spears and the gaff breaking the surface as they stabbed the creature over and over. The water thrashed, a great cloud of brown ink rose to the surface and then Octave was swimming toward the boat, holding the gaff ahead of him with the impaled octopus on it. It must have been about five pounds, thought George.

It was too heavy to fling live into the boat and Octave told George to hit it with the stick over the water. “Attention, it might escape.”” he called. “Hit it, George, hit it!” Climbing aboard, Octave joined George and taking hold of the octopus by the eyes, slammed it again and again against the side of the pirogue. Then he tossed it into the bottom. “Beat it again,” cried George, “It’s still walking.” Finally, the octopus gave up the fight and slid to the bottom, its tentacles still twitching.

In the excitement, the boat had moved much closer to the rough waters by the reef and now both Octave and George took the big gaffs to push it back into deeper water. “Stop the pirogue! Stop it!” Octave called but George caught his gaff in the rocks. “Let go of it. You’ll break it. What are you doing?” George had it loose again and Octave shouted, “Push straight, George, Push straight.”

“Where shall we go?”

“We shall go home. A man gets hungry and the sky is dark. We shall go home, we shall go to eat, drink tea and sleep.” Prem and Karl rejoined them, shivering with the cold, and Octave squatted in the bow and started to sing:

My father is holding your mother fast

My mother is holding your father fast

“When you have octopus,” he told Karl, “you have a taste for fishing. But I lose my taste for it today when the sky is so black. The north wind brings heavy rains, terrible. Once it was winter, I could not get work as a mason and when I got in the boat in the morning I trembled. When you wake up in the morning in winter, (winter in Mauritius is from June through August) you must calculate the cold and rain.”

The boat lurched and George fell into Karl. “What kind of a gogot are you, eh?” Karl too was watching the sky. “Now the darkness is spread everywhere.”

Prem stared at the water itself. It had turned an intense pale green. He had never seen the sea that color before.

“This is in the day; in the night it is more dangerous.” Octave said. The other pirogues in the lagoon were unfurling their sails. “See the fishermen are rushing in every way. I am afraid when we have a north wind. (normally the trade winds blow from the southeast in Mauritius)

Octave shivered. “I am feeling cold. The pirogues are rushing about.” Together he and George lifted the mast into place and let the sail out. It whipped into the wind and the pirogue began moving hard for the shore.

“They have all set sail for home,” said Prem. “We are the last.”

George said, “It’s growing worse.”

Octave reassured them. “It’s nothing. The winter is harsher.”

Karl hunched over, putting his chin on his bare knees. “This weather is only good for going to play rummy.”

“See, all the fishermen are going back to shore,” Octave said. “Have three women, have intercourse, it may be that you can’t because it is too cold. Let’s go walk to the Majestic Cinema. Let’s go to Tardieu Forge.”(the two centers of prostitution in the capital city of Port Louis)

“Karl is the macro (macro: pimp) of the Majestic,” said Prem.

“Watch out,” grinned Karl, making a mock threatening gesture at Prem. “You must experience a storm like this to become a real fisherman. You must have trouble like this. The weather is bad.

“The wind is bringing cyclone-like waves to the reef,” said Octave.

“Like smoke,” said George. “It’s becoming bad, Karl. Look, look, the waves are coming over the reef.”

“Our pirogue is last?” said Octave, grinning. “Oh. Karl, Karl, Karl. Macro of the Majestic.”

“We shall not have a storm tomorrow for the New Year,” said Karl. “We shall put the boat up to dry.”

Suddenly the squall hit. They could see and hear the pelting rain coming across the water toward them and then it was upon them, blotting all sight of the shore and the reef. Nearby a fisherman in another pirogue took in his sail and crawled under it, dropping his anchor to sit out the storm.

“That macro is putting his sail down to hide himself.” Octave said. “He will die. Winter is always like this.”

The heavy rain fell harder-and gradually the strange green sea became calm and they could see the cove again, coming closer. Octave and George huddled down as far into the pirogue as they could, palling their wet tricots over their shoulders but Karl and Prem sat up on the edge of the stern, bare shouldered and turning their faces into the rain.

“If we had a bigger sail it would be good,” said Octave. “Tomorrow it will be calm. Or maybe as soon as you get in the house you will hear the radio saying, ‘A cyclone is coming.'”(Mauritius is hit almost every year by two or three cyclones or typhoons, some of them devastating)

Octave stood up, holding onto the mast, and began to sing.

Oh. Capri. C’est fini.

Et dire que je quitte la ville

Mon premier amour

Je ne sait pas que je retournerai

“This rain will last,” Karl said.

“The rain will be here until afternoon.”

Karl was shuddering with the cold now. “You mast have a woman to get warm again after this.” He shouted to a passing pirogue, “Attention! La Mort! Attention! Beware of Death!” Octave kept singing.

Coca Cola tire du fea (Coca Cola puts out the fire)

Quang mademoiselle ine soif (When young ladies are thirsty)

Li pour demande Coca Cola (They ask for Coca Cola)

Karl grinned at George. “You gogot, just now I will break your liki..” Karl too began to sing. “My priest has intercourse with me, so I yelled to my husband, to my husband, oh!”

Octave asked, “Have you a husband? From where you have this husband?”

Karl said, “Go to hell. Octave is like a gogot in Paradise.”

Octave retorted, “Karl is like a gogot in torn pants. When he fights many go to prison and mast pay bail and some sleep in the hospital.”

George said, “By luck, Benny the Fish Monger will still be there. He will say only forty cents a pound because we are so late.”

The pirogue was nearing the cove, moving quickly now despite the heavy rain. “It’s like a Johnson motor,” said Octave.

“Can you, see Benny on the shore, Octave?” George was anxious to get paid so he could spend the rainy afternoon at the cinema in the next village. He was an addict of secret agent films. But Octave was singing and didn’t answer.

“Twist again, like we did last summer. Oh, twist again, like we did last year ” Octave let go of the mast and started to dance in the bow.

A fisherman called from another boat,, “You might get killed.”

“Little by little we are going to die,” said Karl. “Liki to mama, I am a tired body.”

Through the rain a white youth, standing on the beach in front of a weekend bungalow near the cove, shouted at them, “Where are you coming from?”

“Barracuda Pass,” answered Octave.

“You can have my gogot,” shouted George, telling the others, “I don’t like them. Everywhere I meet them I ill treat them.”

Octave joined in. “A bunch of blancs are a bunch of gogots. Liki of their mothers. A bad bunch. White-skinned Mauritians I don’t like.” (The Creoles, although they are Roman Catholics and have adopted a modified French culture, are often still treated as slaves by the white descendants of their former-masters. Racial relations in Mauritius have much in common with those of South Africa.)

Just then Karl steered the pirogue too close to the shore and it bumped against a rock, George said, “He doesn’t look at the sea. He looks at women, the gogot. Go and have a femme petain, Karl.”

“Couyon,” Karl replied, still watching some girls with umbrellas walking along the shore. “I’ll hit you with the larfine. You are dead. I’ll break your liki.”