A Survey in Two Parts of the Human Impact of Agricultural Development from Prehistoric to Contemporary Times as seen from the Village of Shush-Daniel on the Khuzestan Plain of Southwest Persia

Contents

Part One: 10,000 to 640 B.C. – Bedouin.

PartTwo: Le Temoin – 640 B.C. to the Present – Fellahin The Temple in the Desert

Appendix

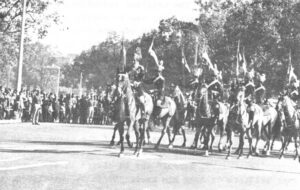

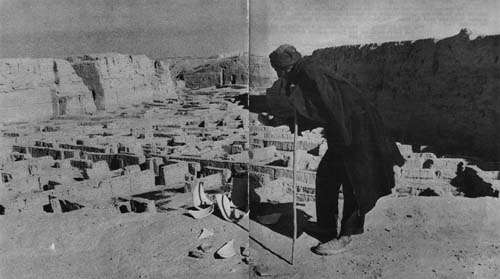

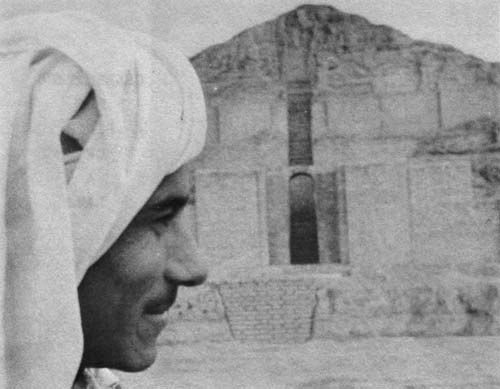

Introductory Note; This report differs from others in this series on food and population in that it is an experiment to see what light can be shed on the previously explored issues of technological revolution, urbanization and the uprooting of people, through a short survey of their historical past. There is consequently, no principal group of characters. Rather this report comprises six sketches, two of them historical exposition and four separate through related scenes of contemporary life, based on dialogue recorded in or around Shush-Daniel village between late December 1970 and early March 1971. Shush-Daniel is today a small settlement of about seven thousand Kurd, Lur and Arab peasants and Bedouins; it is the site of ancient Susa, for many centuries the capital of the Elamites and Achaemenians, and, for a time, of the entire civilized world. Along with Ur. Erech and a few Sumerian temple communities on the Mesopotamian plain, of which Elam (now called Khuzestan) is a geographical extension, Susa was where, with the grain surplus and social differentiation made possible by the introduction of irrigated wheat cultivation, civilization began. A populous city by 3500 B.C. and probably man centuries earlier, built around such temples as the ruined one near Shush shown below, Susa was unique in that it endured as an important urban center for five thousand years, being ruled or plundered successively by the Elamites, the Sumerians, the Babylonians, the Assyrians, the Medes and the Persians, the Parthians, the Greeks, the Sassanians, the Romans, the Arabs, the Mongols and Tamerlane. Its great buildings mysteriously crumbled to dust, its fertile lands faded back to desert and its population vanished in the fourteenth century A.D. No one knows why.

“Before the son and the light, and the moon, and the stars are darkened and the clouds return after the rain; in the day when the keepers of the house tremble and strong men are bent and the grinders cease because they are few, and those that look through the windows are dimmed, and the doors on the street are shut, when the sound of the grinding is low, and one rises up at the voice of a bird, and all the daughters of song are brought low; they are afraid also of what is high, and terrors are in the way; the almond tree blossoms, the grasshopper drags itself along and desire fails; because man goes to his eternal home and the mourners go about the streets; before the silver cord is snapped, or the golden bowl be broken, or the pitcher be broken at the fountain, or the wheel broken at the cistern and the dust returns to the earth as it was….”

The Book of Ecclesiastes

“How lonely sits the city that was full of people! How like a widow has she become, she that was great among the nations.”

The Book of Lamentations

In the beginning God created the heavens and the earth…. God created man in his own image…male and female he created them. And God blessed them and said to them, “Be fruitful and multiply and fill the earth and subdue it.”

The Book of Genesis, quoted during a worldwide telecast by the astronauts on the first manned orbit around the moon, Christmas Eve 1968

The children of Shem: Elam, and Asshur, and Arphazad, and Lud, and Aram.

The Book of GenesisSusa may claim to be the oldest known site in the world.

Brigadier-General Sir Percy Sykes in “A History of Persia”‘It will never be inhabited nor dwelt in for all generations; no Arab will pitch his tent there, no shepherds will make their flocks lie down there. But wild beasts will lie down there, and its houses will be full of howling creatures; there ostriches will dwell and there satyrs, will dance. Hyenas will cry in its towers, and jackals in the pleasant palaces.

The Book of IsaiahThere Babylon, the wonder of all tongues

As ancient, but rebuilt by him who twice

Judah and all thy father David’s house

Led Captive, and Jerusalem laid waste,

Till Cyrus set them free.

Milton, “Paradise Regained”In the days of Ahasuerus, the Ahasuerus who reigned from India to Ethiopia…the king gave all the people present in Susa, the capital, both great and small, a banquet…. There were white cotton curtains and blue hangings caught up with cords of fine linen and purple to silver rings and marble pillars, and also couches of gold and silver on a mosaic pavement of porphyry, marble, mother-of-pearl and precious stones. Drinks were served in golden goblets…

The Book of Esther

Civilizations have always risen and fallen; look at the inner cities of America. Can any affluent society long exist? George Wilson, a 78-year-old California farmer helping to restore the Khuzestan Plain

And the sound of harpers and minstrels, of flute players and trumpeters, shall be heard in thee no more; and a craftsman of any craft shall be found in thee no more; and the sound of the millstone shall be heard in thee no more; and the light of a lamp shall shine in thee no more…. It has become a dwelling place of demons, a haunt of every foul spirit, a haunt of every fool and hateful bird….

The Book of RevelationsMy God, it looks like a Cecil B. deMille set!

An American tourist, seeing the ruins of ancient Elam for the first time, March 1971

The most vital single issue of the 1970s may be the question whether we are capable, on a planetary scale, of finding a way forward between the mindless conservatism of the affluent and the baleful anarchism of the dispossessed… It is remarkable how rapidly the whole political landscape of the post-war years has been transformed. A few recognizable peaks and depressions remain from the forties – ideological division, the Arms race, anarchy between nation-states – but even these familiar themes of the years between the two world wars are charged with new technological force and so changed in meaning they hardly look any longer like landmarks of the past. They belong to a new political country, unexplored, ominous, planetary in scope, and conceivably, bordering on the end of time.

Barbara Ward, January 1971

Now the Shah intends to make Khuzestan bloom once again as it did twenty-five-hundred years ago in the time of Darius the Great, ,when Khuzestan was the breadbasket of the ancient Persian Empire. Oil and gas will pay the bills….

Fortune magazine, November’1970

ANCIENT MESOPOTAMIA

(From W. H. McNeill’s The Rise of the West)

God called the dry land Earth, and the waters that gathered together he called Seas. And God saw that it was good. And God said, “Let the earth put forth vegetation, plant yielding seed, and fruit trees bearing fruit which is in their seed, each according to its kind, upon the earth.” And it was so…. And the Lord God planted a garden in Eden, in the east; and there he put the man whom he had formed…. A river flowed out of Eden to water the garden, and there it divided and became four rivers…. And the fourth river was the Euphrates….

And to Adam he said, “Because you have listened to the voice of your wife, and have eaten of the tree of which I commanded you, ‘You shall not eat of it,’ cursed is the ground because of you; in toil you shall eat of it all the days of your life; thorns and thistles it shall bring forth to you; and you shall eat the plants of the field, in the sweat of your face you shall eat bread, till you return to the ground, for out of it you were taken; you are dust and to dust you shall return.”

…Now Abel was a keeper of sheep, and Cain a tiller of the ground…. Cain said to Abel his brother, “Let us go out to the field.” And when they were out in the field, Cain rose up against his brother Abel and killed him. Then the Lord said to Cain, “Where is Abel your brother?” He said, “I do not know; am I my brother’s keeper?”…. Then Cain went away from the presence of the Lord, and dwelt in the land of Nod, east of Eden.

The sons of Noah who went forth from the ark were Shem, Ham, and Japheth…. The sons of Ham: Cush, Egypt, Put, and Canaan…. Cush became the father of Nimrod; he was the first on earth to be a mighty man…. The beginning of his kingdom was Babel, Erech and Accad, all of them in the land of Shinar…. The sons of Shem: Elam, [The presumed founder of the land of Elam (present-day Khuzestan) and its capital of Susa (now the village of Shush-Daniel)] Asshur, [Assyria + Shinar is Sumer, which, together with Elam, was the worlds first known civilized society; Sumer was first discovered by archeologists in the 1890s but not extensively excavated until the 1920s and 1930s. ] Arpachchad, Lud and Aram…. Now the whole earth had one language and few words. And as men migrated in the east, they found a plain in the land of Shinar and settled there…. And they said to one another… “Come, let us build ourselves a city, and a tower with its top in the heavens, and let us make a name for ourselves, less we be scattered abroad upon the face of the whole earth.” …These were the descendants of Shem.

Excerpts from the first eleven chapters of Genesis

Note: The word, bedouin, is used to describe the pastoral nomadic Arab shepherd of the Middle East and has its roots in the Arabic word, bedou or “primitive” and “of the desert,” and beda which means “beginning.”

10,000 To 640 B.C.

In the beginning the origins of man are a great darkness. Human history, indeed, did not begin until the invention of writing around five thousand years ago and less than two hundred generations of men have lived on earth since then.

Even today the science of archeology is still only in its infancy and shaped stones, potsherds and fragments of bones are pathetically inadequate evidence of vanished human cultures.

It is only in comparatively recent times that archeologists, by comparing styles and assemblages, together with the stratification of the finds, have been able to infer a good deal about the development of man’s tools, his methods of obtaining food and his culture. And this picture is still very tentative; the more one studies prehistoric times and the early civilizations, the more disagreements and contradictions one finds among the experts.

After all, most of the great archeological discoveries have been made during the past century. The ruins of Susa were first visited by Loftus and Churchill in 1850, but the great pagan temple at nearby Chogha Zanbil was not completely unearthed until 1962, an Achaemenian pleasure palace was discovered beneath a village wheat field just two years ago and major digging is still going on. The first evidence of ancient Sumer was not found until 1877, by Ernest de Sarzec at Tello in Iraq. The excavation of Babylon, begun in 1899 by Robert Koldewey, was not completed until 1925. Lord Carnarvon’s expedition to Luxor and the Valley of the Kings on the Upper Nile did not start until 1917. Excavation of Ur of the Chaldees began only in 1918 and the famous Death Pit with 450 royal graves was not found until 1928 by Sir Leonard Woolley. The antique city of Mohenjo-Daro in Pakistan, almost as old as Susa and Ur, was not found until 1922 by John Marshall. As late as 1947 a Bedouin shepherd found the Dead Sea Scrolls in a cave which contained a scroll of Isaiah, dating from the second century B.C. and threw new light on the New Testament. It was not until 1952 that William F. Libby published his method of radiocarbon dating to determine the age of organic substances and only two years ago that rocks brought back by the astronauts established the age of the moon at 4.6 billion years. As recently as February, 1970, the foundation stones of Darius the Great’s palace at Susa were discovered, enabling the Iran government to undertake an extensive reconstruction. And it was only three months ago that Harvard University’s C. C. Lauberg-Karlovsky disclosed evidence of a previously unknown civilization half-way between Susa and Mohenjo-Daro which may have been contemporary with both in 3,500 B.C.

Curiously, the more man learns through modern scientific methods of his remote past, the more the Old Testament is confirmed as a remarkably reliable historical document. In treating it as such, one must be careful to draw a distinction between those parts of Genesis which precede the invention of writing and, passed on orally from generation to generation, must be regarded as symbolic myths, and those parts presumably based on some sort of written records. The dividing line between remembered legend and historical reality appears to be the story of Noah and the Ark and the Flood, for which considerable archeological supporting evidence exists.

Thus, in this short historical review, I shall advance the thesis that the first five chapters of Genesis the story of the Creation, Adam and Eve, the Garden of Eden, the Fall and the story of Cain and Abel fall together in the realm of a legend evolved by men after the dawn of civilization in Mesopotamia and after the beginnings of agriculture, the event of towns and temple cities and primitive warfare, to symbolize the happy anarchy and simplicity of human life in the Neolithic Age. To put some dates on it, the written records on which the Old Testament’s opening book is based seem to go back no later than around 2,400 B.C. or almost a millennium after the invention of writing itself, and hence the first five chapters of Genesis represent the contemporary collective memory of life bf the Mesolithic and Neolithic periods, or before the beginnings of agriculture around 6,250 B.C. (give or take a couple of hundred years.)

I shall also advance the thesis that a new style of life had emerged in Elam by 4,000 to 3,500 B.C. that equaled that of nearby Sumer in complexity, wealth and general impressiveness and is equally deserving to be described with the phrase, “the dawn of civilization.”

In terms of the earth’s existence, human civilization is a very new development. We know that some form of manlike creature, described as Australopithecine, existed in the early Pleistocene geological epoch of 1 million to 500,000 years ago. Pithecantrophus erectus, perhaps the “missing link” between the primates and ourselves, lived in Java during the middle Pleistocene period of 500,000 to 100,000 years ago, as did Peking man in China, who left traces of fire in his cave.

Neanderthal man of the late Pleistocene epoch knew both fire and tools in Europe but vanished, either through disease or from being slaughtered, with the advent of Homo Sapiens or modern man some 30,000 to 40,000 years ago. The emergence of Homo Sapiens coincided with the withdrawal of the last great glacial ice sheets and, by 10,000 to 15,000 B.C., the establishment of the earth’s present climatic zones.

The first traces of human remains from the period 10,000 to 15,000 B.C. in the vicinity of the Mesopotamian Plain were discovered by Professor R. Ghirshman, the leader of the French Archeological Mission in Iran, in a cave in the Bakhtiari Mountains not far from Susa in 1949. One of the last of the cave men, this human was a hunter who knew how to use a stone hammer, the hand-axe and the axe tied to a cleft stick. He already used pottery, although it was crude and black in color, presumably due to the use of smoke in firing. The findings suggested the pottery was copied in clay from basket and gourd shapes, possibly invented out of the need for a fireproof and waterproof container to cook cereal porridge from the wild barley and wheat. His cultural evolution was already well advanced I necessitated by the helplessness of the human young and the caveman s need to instruct his offspring in the arts of life if they were to survive despite their unimpressive teeth and muscles.

The cave woman appeared to have special tasks: she was the guardian of the fire and the collector of roots and wild berries in the mountain forests, while her husband remained the hunter.

There is little archeological evidence just when and how this caveman and his woman became shapers of the animal and vegetable life around them, rather than mere predators upon it. But it occurred sometime around 10,000 to 8,000 B.C. and was a radical turning point since the whole history of civilized mankind up to the present day has depended on the enlargement of the human food supply through agriculture and the domestication of animals. (Reaching its extreme, of course, in modern America where in a few years less than 3 per cent of the populace is expected to feed the rest in an economy whose gross national product is well over a trillion dollars.)

The price was high, however, for the hard labor of tilling fields, and grazing sheep and cattle was a poor substitute for the joys of the hunt, as is suggested in the vivid poetry of God’s curse upon Adam.

It seems most probable that women invented agriculture. Knowledge of plants, born of a collector’s long experience, must have led them to experiment. Seed bearing grasses probably grew 10,000 to 12,000 years ago in the Anatolia and Zagros mountain foothills and valleys as they do today. The cave woman’s first attempts took place on the alluvial terraces where we can imagination a succession of breakthroughs: (1) allowing a portion of the seed to fall on the ground and discovering this assured a crop the next season, (2) learning to scatter seed on prepared ground and (3) breaking the ground with a digging stick and covering the seed to keep it from birds. Culturally, this may have led to a temporary imbalance between the roles of men and women. It suggests why women have been so predominant in many primitive societies and why female priestesses and goddesses emerged along with early agriculture.

Our knowledge of the transition from hunting to domestication of animals is even dimmer; it may have had its origin in man’s need of animals for blood sacrifices.

What is known is that the progressive drying up of the valleys in the Anatolia and Zagros mountains after 10,000 B.C. caused animals living in them to gradually descend these newly-formed grasslands and eventually to move out onto the open Mesopotamian Plain. Here the climate was Mediterranean, the vegetable cover was thinner than the better watered foothills to the north and east and the summer was very hot, but there was, and still is, a scattered growth of trees and vast fields of natural grasses, which fed with winter rains, luxuriate in the spring only to wither in the summer and revive again the next year. By contrast, the hillsides and mountain slopes remained thickly wooded on their windward side. It was an ideal landscape for human habitation.

What did man bring down from the hills with him? The oldest village settlement in the region, at Siyalk, south of Teheran and east of Susa, reveals how the earliest farmer lived on the plateau. He had no house but built himself a hut of tree branches; he began to paint his pottery but still used no wheel; he had an all-stone tool kit: flint knife blades, sickle-blades, polished axes and scrapers. Both men and women wore necklaces of shells and carved stone rings and bracelets; man had become a skilled bone carver and apparently had cloth; one bone carving, the earliest representation of a clothed man in the Middle East, shows him wearing a cap and belted loincloth. His dead were buried beneath the ground of his house and he apparently already believed in life after death since he took an axe and food to the grave with him. Although he was still a hunter and fisherman, he had domesticated sheep. He even knew trade since some of his ornaments were seashells from the shores of the Persian Gulf. All the evidence suggests he was very free; the transition to peasant laborer that he was to later experience on the plains had not yet begun; it was soon to become one of the greatest revolutions in man’s long story, creating tensions and repercussions that continue very much to this day, as we shall see. Indeed, it was possibly the happy anarchy of his existence and later memories of this Neolithic Age that was to inspire the legendary memory of the expulsion of man from Paradise.

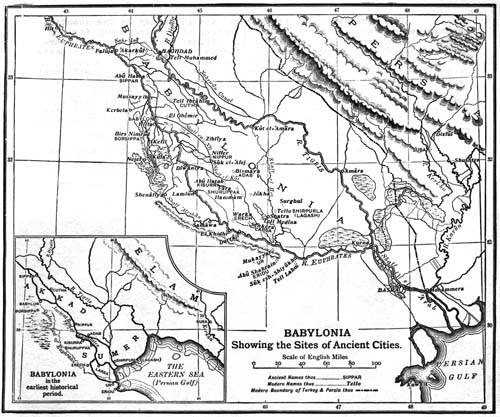

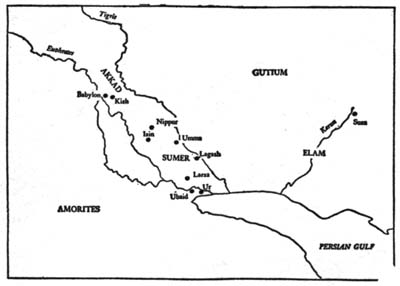

At this point it should be noted that the Khuzestan Plain (which with the Zagros foothills comprised the ancient land of Elam) represents a geographical extension of the great Mesopotamian alluvial plain. Mesopotamia, literally the “land between the two rivers,” the Tigris and the Euphrates, has traditionally been regarded as a trough slowly filling with alluvial soil carried down from the Anatolia and Zagros mountains. (Elam was, and is, watered by the Karun River, a tributary of the Tigris.) It was previously assumed there had been a regular withdrawal of the Persian Gulf before the advancing deltas of the three rivers. New resources of data, however, such as soil surveys, hydrographic reports and aerial photographs, have revealed that the entire basin is in fact a complex and unstable geosyncline which has probably tended to settle as fast as it was filled.

Moreover, the upper Khuzestan Plain where Susa is situated, possesses increased surface gradients and widespread underlying gravel deposits which minimize the problems of salination and water logging usually associated with irrigation agriculture. The Susa region also receives some 300-millimeters yearly of rainfall, well above the 200-millimeter isohyet considered the absolute lower limit for primitive grain cultivation. (A recent test in the region of Susa showed average net wheat yields of 410 kilograms (about 6 bushels per acre) from dry farming as compared with 615 kilograms per hectare on irrigated land.) Dr. Robert M. Adams of the University of Chicago (See his “Agriculture and Urban Life in Early Southwestern Iran,” Science, CXXXVI 1962 112-13), after an extensive study of these factors, concluded that while irrigation on the upper plains around Susa “is a valuable adjunct in the cultivation of the basic cereal crops during the traditional winter growing season … it is by no means an indispensable condition for the practice of agriculture.”

The surface gradients and underlying gravel deposits in the Susa region were advantageous in the early stages of the development of irrigation, since they permit an adequate flow during the winter growing season with relatively short and easily maintained canals. In addition, the pebbly soils in the upper portion of the Susa plain or Susiana as it was called in ancient times, receive natural subirrigation from underground springs, while rainfall from the mountains is carried out onto the plain some distance by numerous winter and spring freshets. This is one reason why the upper portion of the Susiana plains abounds in rich natural pastureland if not overgrazed and wild narcissi still flourish here.

This and other evidence – no traces of early Neolithic agricultural settlements have yet been discovered on the Mesopotamian plain proper – suggests that man, having learned wheat and barley cultivation and sheep herding in the foothills and mountain valleys, made the vital transition from dry farming to irrigation agriculture on the Elamite or Susianian plain around Susa and that it was here, rather than in Mesopotamia proper – which after all lies only fifty miles to the west of Susa – that civilization as we know it truly began. [It is hoped such a flat assertion might arouse controversy. Elam and Susa have been so under publicized it was still possible last year for an excellent study, The March of Archaeology by C. W. Ceram to be published with only one mention of Susa or Elam, and that in the index.]

The oldest village sites of the Susiana plain and the surrounding foothills date from around 8,000 B.C. at Shogamish and Dehloran and 6,000 B.C. at Jafar Abad and Shush itself, so that we know definitely that some humans had moved down from the hills to the plain as early as ten thousand years ago. In contrast, the first evidence of agricultural settlements of any size in Mesopotamia proper, comes around 4,000 B.C. or much later.

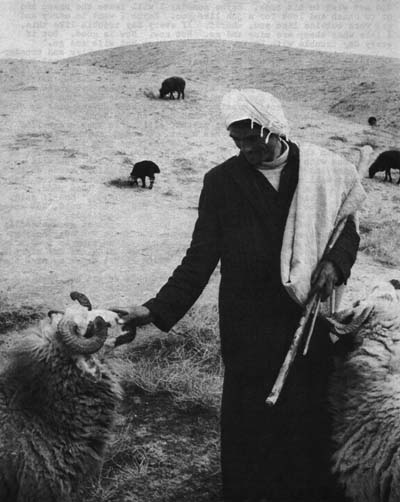

The first agriculturalists in the hills were not – as the tree-branch house at Siyalk suggests – were not fully sedentary, but like l8th century pioneers in America preferred the woodlands and clung to the slopes and foothills where trees grew naturally. This style of slash-and-burn agriculture involved a semi-migratory pattern of life and also the occupational divergence of early man into two distinctly different styles of life: hunters who found field labor little to their liking and adopted instead the arts of the herdsman, and the settler, who became a sedentary peasant farmer. As in the book of Genesis, “Abel was a keeper of sheep, and Cain a tiller of the soil,” and a perennial warfare was to develop between peasant and herdsman that continues in Khuzestan, as elsewhere, to this day, in the constant conflicts between the Arab bedouin, or sheep-raising nomads, and the fellahin, or peasant farmers. Of course, there was also from the first some economic intercourse between the two life-styles, the pastoralist feeding their flocks on the grain stubble, as they do today, and the farmer in return obtaining milk, wool and manure from the shepherd.

+Although also at Shush there is some evidence of human habitation somewhat earlier. One does not have to look far for the reason. In the words of Ezzat O. Negahban, chairman of the Department of Archeology at Tehran University, the French Archeological Mission in Iran had a “virtual monopoly” over diggings in Khuzestan as elsewhere in Persia until a Law of Antiquity was passed in 1939. Today 40 foreign and 15 Iranian archeological teams are digging. Consequently, although there are a few excellent books on Susa and Elam in English, the bulk of knowledge about them remains untranslated from the French, including some seventy volumes of the findings of the French Archeological Mission in Iran. In result, popular writers of books on prehistory and ancient history tend to bypass altogether such sources. Hence we know much more about Pompeii and Herculaneum, Babylon and Percepolis, the tombs in Egypt than we know about Susa, which overshadow all the rest in historical importance,

In the earliest major phase of settlement around Susa, covering a long span from around 6,000 B.C., a few centuries after the beginning of agriculture in the hills, to about 4,000 B.C. there were at least 130 village sites, although most of them date from the later part of this span. This high early density reinforces the belief that the region offered exceptionally favorable circumstances for the transition from dry farming to irrigation agriculture. There was enough rain for dry farming while rudimentary irrigation systems were being developed, together with the suitable slopes and soils and the numerous, easily diverted watercourses.

Of these sites, the earliest 34 all have been found close to the foothills where rainfall is heavier. Many are so located that irrigation would not have been possible; it appears this earliest phase of settled agricultural life depended almost exclusively on rainfall.

A few centuries after 5,000 B.C. the number of known villages jumped to 102, many of them much further to the south than the earliest phase but still conforming roughly to that existing today for villages partly depending on dry farming and partly on irrigation. Thus we can assume that between 6,000 and, say, 4,500 B.C. some irrigation practices had been introduced and that this led to a greatly expanded population. (Some archeologists believe that the human population all over the world multiplied about 16 times between 8,000 and 4,000 B.C. as a consequence of the introduction of agriculture.) The early agriculturalists of the Susa region appeared to farm with flint sickle-blades, hard-baked clay sickles and stone hoes and continued to hunt as well with flint arrow heads and pottery paintings of bowmen in the pursuit of wild game, as well as carved gazelle bones, attest to the importance of this earlier way of life.

Gradually, however, male leadership in the hunt ceased to be of much importance. As the discipline of the hunting band decayed, the political institutions of the earliest plain settlers came close to the anarchism which has remained ever since the ideal of peaceful peasantries all over the earth. In contrast, those who remained pastoralists, developed quite different traditions; to protect the flocks from animal predators required the same courage and male prowess of the hunter; hence the pastorlists developed a system of patrilineal families (as opposed to the settlers; the Elamites would inherit property through the female line), unity under kinship groups under the authority of a chieftain responsible for daily decisions as to where to seek pasture. The shepherds were also likely to have attached more importance to the practices and disciplines of war. As we shall see later, these characteristics still survive among the Arab Bedouins of the deserts near Shush-Daniel today.

In the last centuries before 4,000 B.C. the pressure of population and search for new cultivatable lands seem to have led to the settlement of the Mesopotamian plain between the Tigris and the Euphrates. Perhaps this took place as early as 4,500 B.C. although recent findings suggest a somewhat later date. By this time, it should be noted, villages were beginning to appear along the banks of the Nile at the other end of “the fertile crescent,” and “Danubian” cultivators appeared in central and western Europe. In the Far East, a similar agricultural expansion did not take place until much later, around 2500 B.C. in China, for instance. By contrast, at the same time in America, a previously uninhabited land, Homo Sapiens was just arriving.

Many archeologists believe the earliest settlers of Mesopotamia came from Elam, where the villagers were of similar Sumerian-Semitic stock. But the origin of the Sumerians remains unestablished and we have only the Bible’s “And as men migrated in the east, they found a plain in the land of Shinar and settled there.” Certainly, the “land between the two rivers” offered many attractions to the mountaineers and newly-settled plainsmen near Susa with its fish and fowl, easily-worked alluvial soil, many date palms to supplement a cereal diet and the annual flooding that always brought a fresh top dressing of silt.

How and when the traction plow is invented is not clear. By the time of the proto-Elamite tablets, dating from toward the end of the 4th millennium, signs representing orchards as well as fields appeared and the existence of a plow can be demonstrated. Crude plows are familiar from the earliest Sumerian and Egyptian records, which date from a few centuries afterward. Cattle, particularly oxen, were apparently widespread by then and the earliest plows appeared to have been pulled by hitching a knot around their horns. But the first plows had no moldboard to turn a furrow and simply scratched the earth breaking the surface into loose lumps by driving a flat share some inches below the surface of the ground. Cross-plowing and the squarish field shapes that went with it appeared from almost the beginning.

The harnessing of animal power and the spread of traction plowing served to reverse the roles of the sexes in agriculture; when animals went into the field, men followed them and in turn men were able to reinforce or restore masculine primacy in family and society. With the exception of Elam, by the time of the earliest written records, patrilineal families and male dominance was universal among plowing peoples of the Middle East.

A few bits of copper on village sites also attest the beginnings of metallurgy as well as demonstrating the limitations of developing skill in a village context. The attainment of professional skills had to wait, and was the distinguishing mark of the earliest, civilized societies.

Elam appears to be the first civilized state in human history, emerging sometime around 4,000 B.C. Its founder and namesake, if the book of Genesis is to be believed was a grandson of Noah. During the last centuries before 3,000 B.C. it created its own-writing, the still-to-be-deciphered “proto-Elamite,” before it was rapidly overtaken and overshadowed by the remarkable advances of the Mesopotamian cities to the west. At the same time, from 3,500 to 4,000 B.C. the number of settlements on the plain around Susa rapidly declined, from a known 130 to 39, although some of those which remained grew to cover 10 to 15 acres and could be classified as small towns. A sharp cultural break is also evidenced in pottery for the exquisite painted pottery whose beauty was never again to be equaled, suddenly stopped and was replaced with a monochrome red ware with a handle and tubular spout. The same thing also occurred in Mesopotamia and toward the end of this period in both Mesopotamia and Elam, man invited writing.

One looks for a reason for this decisive shift; why did the number of village settlements fall to just over a third of their previous number? The obvious one is that the population was regrouping into larger, more defensible units and about this time some of the towns in Mesopotamia began to attain truly urban status and to be enclosed by massive walls. Small-scale irrigation, the planting of intensively cultivated gardens and orchards and plow cultivation were all adopted increasingly within limited enclaves around the towns. Susa itself is buried too deeply under the debris of later civilizations to learn much of its origin or early size although it was a populous city by 3,500 B.C. as evidenced by one cemetery of this date filled with 2,000 mostly wealthy citizens. The earliest town we are certain emerged prior to 4,000 B.C. is Eridu in Mesopotamia.

What is clear is that as suitable soil was reclaimed from the wooded slopes and the land became more fully occupied, the pressure of a multiplying population caused settlers to move outward in all directions. And that soon after 4,000 B.C. agricultural settlements equal in size and elaboration to those in the partly-rain fed Elam had begun to appear along the lower Tigris and Euphrates, just 50 to 100 miles to the west. The inference is obvious: pioneers in Elam had learned to bring water artificially to their crops, and now were applying it. The techniques of irrigation were probably tried out along the banks of the Karun and Karkheh rivers in Elam, where ordinary cropping failed as the streams emerged from the relatively well-watered hills and debouched into the Mesopotamian desert lowland. In this strikingly new environment, where swamps made fishing and fowl-snaring an important activity, stock-raising was possible on the fringes of farmed lands and fishers, herders and cultivators lived cheek by jowl, it is not surprising that there emerged a class of managers with authority to adjust disputes. The flat and nearly stone-free terrain of Elam and Mesopotamia made plowing easy and the rich alluvial soil made it possible to produce an agricultural surplus sufficient to support a managerial class. [In other words, irrigation was developed in Elam first, making the settlement of Mesopotamia proper possible.]

This social evolution was probably not intended or even desired by the early settlers since it quickly gave rise to a priestly class who assumed the role of managers, planners and coordinators of a massed human effort that gradually took over building canals and irrigation works, town walls and temples and eventually monumental architecture. In time the authority of the priestly classes became very great, but their services of calculating seasons, laying out canals and keeping accounts and law and order became vital. In turn, the priests of Elam and Sumer gradually evolved a theology that held men to be expressly created to slave for the gods and that if men did not serve them ceaselessly and assiduously he was threatened with direct divine punishment – flood or drought and consequent starvation.

Thus, for the first time in the story of man, the temple community technically permitted and psychologically compelled the production of an agricultural surplus and applied that surplus to support specialists who were to become the creators of civilized life. A second great achievement, along with the temple community organization of community life for the peasantry, was the slow and partial development of a looser social unit, the great secular society of intellectuals, lawyers, administrators, soldiers and merchants.

Between 3,500 and 3,000 B.C. when, with the invention of writing, human history begins and the story of prehistoric man ends, human culture began developing in all directions.

Susa lay so close to the larger Tigris-Euphrates complex that the originally independent growth of Elam with its earlier civilization was soon submerged by the superior culture of Mesopotamia. After all, the distance from Susa to the Mesopotamian towns and cities was not far: Ur was only 130 miles away, Uruk, 160 miles, Lagash, barely 100 miles. Trade was very lively between Susa and Ur and Uruk by 3,500 B.C. facilitated by the inventions of the wheel and the sailboat. Trade also began with new civilizations springing up on irrigated river valleys of the Nile and the Indus as well as near the banks of the Jordan where a great spring of water provided the basis for the early rise of Jericho. But all were small islands of civilization (Mesopotamia was smaller than Holland) in a vast ocean of barbarism.

The cultural development of Sumer is one of the richest the world has ever known. Among other things, the Sumerians gave the world its sexagesimal metric system, the 60 minute hour, the 60 second minute and the 360 degree circle. (The Elamites devised the decimal system.) Writing was invented as early sign lists made to record an agricultural and pastoral economy based mainly on the temple’s services and requirements, although it gradually spread to private business and other uses.

But agriculture tells. Sumer’s decline after little more than a thousand years was due to excessive irrigation, lack of drainage and salinization which in time made grain cultivation impossible. (A good record, though. The same thing happened in the Imperial Valley of California in only 30 years.) Leaching was unknown and it was perhaps inevitable that the Elamites, with their superior soil and topographical conditions, should be the ones to overrun and conquer the two main Sumerian cities of Ur and Uruk in 2,000 B.C., carrying back the last Sumerian king, Ibbi-Suen, in captivity to Susa. Indeed, Elam was to survive as a nation state or center province within a world empire until the arrival of Alexander the Great around fifteen centuries later. And as a city, Susa would outlive Ur and Uruk by three thousand years.

As early as 2,500 B.C. Susa was already a populous city and an ancient one; some of its buildings must by then have gone back 1,000 to 1,500 years. The nouns of the Sumerian language, which had already replaced the earlier proto-Elamite as the linqua franca, give some idea of the life of the times: “ox, cow, calf, goat, pig, lion, deer, mouflon, hound, vases, spouted drinking pots, seed-ploughs, nails, ploughshares, harrow, axe, spear, dagger, bow and arrow, harp or lyre, boats, two and four-wheeled carts, copper, carpenter, priest, blacksmith, chief, herdsman.” Only two gods appear in the writing of the time, Enlil, god of the wind and storm and Inanna, the fertility goddess. A “glorious array” of temples already adorns the Mesopotamian plain and its extension around Susa. Slave labor has been introduced, most slaves abducted from the less “civilized” inhabitants of the Anatolia and Zagros mountains.

The rule by priests was giving way to rule by kings and the Royal Standard of Ur unearthed in 1928 along with 74 persons buried with a dead king gives some idea of the court life at the time (the first known king of Summer, having appeared in 3,000 B.C. although the Standard dates from 2,700 B.C.) divided into two panels, its “war” side depicted heavy four-wheeled chariots with solid wheels drawn by wild asses and a procession of prisoners led by soldiers with short spears, felt cloaks and leather helmets before the king in a chariot. The “peace” side showed servants leading wild asses, carrying heavy bundles strapped to their heads, as porters do today in Nepal or Kurdistan, bullocks and rams, a servant carrying a platter of fish, another wine, a third a lyre and others bread.

*with the growth of towns, family-sized farms were gradually replaced in Elam with estates relying on serfs or slave labor.

By now civilization had spread throughout the fertile crescent, the strip of land between the mountains and desert that loops past the hills of Palestine through Syria, then southward into Mesopotamia, ending in the hills past Susa. “Civilization ends at the Zagros Mountains,” wrote a scribe of the time.

Although writing commenced about 3,000 B.C. literature did not really appear for about a thousand years. One of the first efforts was a despairing cry from an unknown Sumerian found on a clay tablet, perhaps mankind s first poet: “My god … for me the day is black…. Tears, lament, anguish and depression are lodged within me….”

In temple ceremonies, the priests portrayed the Sumerian race as the founders of civilization, men formed from clay by the gods who had made them, Enlil, “King of Heaven and Earth,” who then transformed a flat, dry, windswept land into a green and fertile realm.

Without Enlil, sang one early poet:

No cities would be built

No settlements founded

No stalls built

No sheepfold erected

No king enthroned

No high priest born….

In field and meadow

The rich grain would not flower

The trees planted in the mountain forest

Would not yield fruit.”

Thousands of tablets of clay, written on by a reed stylus, have been found at Susa, Ur, Uruk and other contemporary cities. They record constant conflicts between herdsmen and farmers and in at least one old legend the agriculturalist is mocked by the nomad as a man of “ditch, dike and furrow.”

There were also love poems:

“Bridegroom, dear to my heart

Goodly is your beauty, honeysweet.

Lion, deer to my heart

Goodly is your body, honeysweet.

You have captivated me

Let-me stand trembling before you

Bridegroom, I would be taken by you to the bedchamber

Bridegroom, let me caress you.

My caress is more savory than honey.

Hundreds of tablets of schoolboys have also been found, reading rather like a modern youth’s diary:

“When I awoke early in the morning I faced my mother and said to her, ‘Give me my lunch I want to go to school.’ My mother gave me two rolls of bread and I set out…. In school the monitor in charge said to me, ‘Why are you so late?’ Afraid with pounding heart, I entered before my teacher and made a respectful curtsy.” Apparently this did no good for a few words later in the cuneiform markings is the sign for “stick and flesh.”

The residential quarters in those days – one can walk through an extremely well-preserved one from about 2,500 B.C. at Shush today – were crossed by broad avenues intersected by narrow, winding alleys. The houses had a court-yard and many rooms, which seem very small and cramped-looking to a modern visitor. The families slept on narrow wooden beds (unlike the present inhabitants of Shush, who mostly sleep on carpets on the floor.) Servants or slaves put away the beds during the daytime. Girls did not go to school but boys went all year round. Both men and women dressed in white cotton togas which they wrapped around as did the Romans two thousand years later, leaving one shoulder bare. Many of the men shaved although some had beards and long hair (one sees both in Shush today.) A chiton or long skirt (see photograph pages 4 & 5) was worn when dressing up with a fringed shawl hung over the left shoulder. The diet was mostly composed of milk, dates, bread and a few vegetables, exactly as it remains today. A wealthy man’s home could comprise 12 to 20 rooms and be plastered white brick with a garden in the center. The women wore rouge, lipstick and daubed their eyes with mascara and wore perfume.

In Susa, there was a “promenade street” where young people met, just as they do in contemporary Shush; marriage contracts were drawn up and “certified” with cylinder seals. Final wedding arrangements were made by the fathers.

The proverbs of the time suggested that in its essentials, life was not so very much different from ours: “Who has not supported a wife or child, has not borne a leash,” “For his pleasure – marriage. For his thinking it over – divorce.” (which was not uncommon) “‘The wife is a man’s future; the son is a man’s refuge; the daughter is a man’s salvation.”

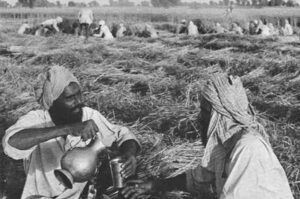

Susa in those days four thousand years ago had wheat and vegetable farms around it and it is remarkable how little methods of cultivation have changed from then until now. Then, as now, fields were trampled and leveled with oxen, water was released from dikes with shovels to give moisture to the soil. Lentils and onions were grown, as well as chick-peas, turnips, mustard and leeks, wheat and barley. In those days the farmers sang a hymn to Inanna, the goddess of fertility:

May the watered garden produce honey and wine

In the trenches may the lettuce and cress grow high

…May the holy queen

…Pile high the grain

There was one great difference; the farmer of Susa four thousand years ago would probably have held a whip in his hands and would probably have explained to a visitor that at times his slaves needed to feel the lash. For early civilization was built on slavery as much as irrigation – mostly captured prisoners of war – and the cost of a man was 20 shekels, less than the cost of an ass. For civilization was, and is, a two-edged thing. For every positive gain in technological advance the price has been some portion of man’s humanity. If there is one recurring theme in human history, it is this; and the bewilderment of many Americans in the space age and epoch of the computer, mass communications and mass political manipulation seems very similar to what the early peasants of the Mesopotamian plains must have felt at around 2,000 B.C.

Disillusionment began to set in within Sumerian and Elamite society after 2370 B.C. when Sargon the Great of Akkad, the leader of a Semitic people, established control over most of Sumer and the whole of Mesopotamia. With bow and sword and battle-axe, Sargon may have carved out an empire that reached from Ethiopia to India. But his dynasty lasted less than a century. About 2,200 B.C. the Guti tribes of the Zagros Mountains above Susa, who were called “the snake and scorpion of the mountain” and had female generals, swept down and conquered both Elam and Sumer covering “the earth like the locust.”

The Sumerian civilization survived for one last great dynasty under King Ur-Nammu of Ur, who built the towering ziggurat of Ur, renovated the canals and “made straight the highways.” Ur-Nammu also drew up the oldest law code known to man. Yet Sumer was already too torn by internal strife, too threatened by Semitic nomads from the western deserts, when the Elamites struck. In a pathetic appeal for help, King Ibbi-Sin wrote an epitaph for Sumer, “Lo, in the assembly of the Gods, Sumer has been prostrated.”

* The Mesopotamian cities of around 3,000 B.C. were relatively small; Ur is estimated to have had some 35,000 people and Susa, 40,000

The technique of writing appears to have evolved slowly from a mere recording of temple business transactions into the transcription of old myths and temple scripture which had previously been handed down orally from generation to generation.

Literature does not seem to have emerged until the two hundred years between 1,800 and 1,600 B.C. when the two great works that survive, the Epic of Gilgamesh and the Epic of Creation, were written. Both poems represent a denial of the adequacy of received religious doctrine.

The Epic of Gilgamesh draws on the story of the Flood, then firmly implanted in Mesopotamian minds. In the Sumerian version, the gods decreed the destruction of the seed of mankind and all that grew upon the earth. But some of the deities demurred and decided to warn one pious man, Ziusudra. He built a great boat, then “all the wind storms, exceedingly powerful, attacked as one.” For seven days and seven nights, the flood swept over the land but Ziusudra safely rode it out. Then Utu, the sun god, came forth and “brought his rays into the giant boat.” Ziusudra sacrificed an ox and a sheep to the gods, who awarded him immortality. And the seed of man once more flourished on the earth.

In the Epic of Gilgamesh, the hero, apparently a Semitic nomad who really lived but became wrapped in legend, is a passionate seeker after immortality but he cannot find eternal life despite all the advice he receives from Ut-Napishtim (Ziusudra or Noah). He must die. But Enlil, the father of the gods, appoints him lord of the underworld. In ruling over what he feared, he loses his fear. And in Gilgamesh we have that first note of defiance expressed by Milton’s Lucifer so grandly, “Better to reign in Hell than serve in Heaven.” [Elam figures importantly in the Gilgamesh legend.]

By the early Sumerians, the Flood is treated rather as a fact than as a legend. In a list of kings unearthed by archeologists during recent years there is a curious footnote appended by the Sumerian scribe to the “List of Larsa No. 1, The First Dynasty.” The appended explanation said, “Now came the Flood. And after the Flood the kings of the Mountain peoples assumed dominion.” The most logical explanation of this is that to the Sumerians as with the Book of Genesis, the dividing line between remembered legend and at least orally recorded history was the Flood and that the “mountain peoples” are the new settlers moving in from the Zagros foothills and Elamite plain.

Just as the Epic of Gilgamesh protests against the injustice of the gods in refusing to men the gift of eternal life, so the Epic of Creation consciously reshapes old myths to justify the exaltation of Marduk and his city. (Marduk was the patron god of Babylon.)

It was a time of questioning. And I think we assume at least the source documents from which the first nineteen or so chapters of Genesis were taken, were set down by this period if not earlier.

To return to the Old Testament from the story of Noah and the Ark onward we have left the realm of legend and entered that of rather accurate history. Virtually all of the people, place names and events from here on turn out to be real people and places and events confirmed by secular archeological science. It is my belief that the more archeologists discover of the past the more confirmations will take place, in other words, the Old Testament, in our secular, spiritually rootless, modern age turns out to be an excellent historical document. Historically, the early symbolic legends aside, the old Testament is the story of the Hebrew people from around 1950 B.C. to around 400 B.C. or around a hundred years before the rise of Alexander the Great, a historical span of about 1,500 years. The New Testament covers a much briefer period, from 4 B.C., the probable date of the birth of Jesus to the martyrdom of Paul in Rome under Nero around 64 to 66 A.D. The Old Testament, especially, gives remarkable glimpses into the world of its times, dominated by the Elamites, the Sumerians, the Babylonians, the Assyrians, the Egyptians, the Medes and the Persians and other great societies of the times. I suppose Biblical scholars – and our grandmothers – know this, but it came rather as a surprise to myself, educated mainly in the second half of the twentieth century when people no longer read the Bible as they once did. And we have a great advantage that our great-grandmothers and great-grandfathers did not have; the existence of Sumer, the land of Shinar in Genesis, has only been confirmed in the past 90 years.

For instance, the tenth chapter of Genesis lists the generations of offspring that were born to Noah and his sons. Many of the names are not known. But the Nimrod, who is described as “a mighty hunter before the Lord,” is almost certainly Sargon, who, as mentioned earlier, assumed power in 2,370 B.C. and established Semitic control over a large part of Mesopotamia. Genesis describes the “beginning of his kingdom” as including Erech (Uruk) and Accad and says they are in the land of Shinar, which has been archeologically confirmed.

Then follows the story of the Tower of Babel, the tower men built with “its top in the heavens.” This is clearly a reference to the lofty, terraced pyramid-like structures called ziggurats, of which the remains of twenty have been found, the largest and best preserved among them at Chogha Zanbil, a ruined temple city less than twenty miles from Susa and built to serve its kings. The ziggurat, man’s first attempt at monumental architecture, was rather a late Sumerian development (the one at Susa being constructed only in 1,300 B.C. and the one at Ur during the neo-Sumerian revival of 2,028 to 2,003.) Thus the Tower of Babel story, which follows in good chronological order, presumably has its basis in some historical event. It must be remembered that the stories in Genesis are told by men of a Semitic Bedouin nomadic tribe with an extremely high regard for the written word, a regard Jews have retained down through the ages. They did not subscribe to Sumerian religious doctrine and presumably regarded the vast pyramid-like brick structures, crowned with their sky-blue temples housing pagan gods as monumental symbols of human arrogance. “And the Lord scattered them abroad over the face of all the earth” probably implies, the kings of priests of Sumer and Elam were getting their just deserts.

The next historical event we find in Genesis is the departure of Abram* from Ur of the Chaldeans. Or as it is told in the Bible, “Now these are the generations of Terah: Terah begat Abram, Nahor and Haran; and Haran begat Lot. And Haran died before his father Terah, in the land of his nativity, in Ur…. ” At that time the ziggurat or giant earthen temple of Ur was only fifty to one hundred years old. Rising seventy feet high, it must have resembled an immense holy mountain of sun-dried bricks. Today Ur lies in an abandoned desert of salted earth and Ur is no more than a heap of low mounds, smooth with age and a few fallen walls. In Abram’s time it was already old, bustling, prosperous, a commercial center somewhat past it’s prime. Priest-ruled and merchant ridden, it offered luxury to the privileged and squalor and subsistences to its slaves and peasants. Yet artisans plied crafts with skills unequalled in all the world save Egypt and astrologists, applied the newly discovered science of mathematics to the stars in hopes of unraveling the mysteries of astrology and astronomy. In temples scribes practiced writing. Narrow streets ran crookedly between the houses of baked and unbaked brick such as still exist in the Middle East today, hiding cool gardens and considerable elegant living behind them.

Abram and his father were not people of Ur but herdsmen from the desert and natural grasslands upstream; they spoke a strange tongue and lived in black tent encampments outside the city wall.

Abram’s departure to the land of Canaan ends mention of Elam and Sumer in the Old Testament until Susa re-enters dramatically as the capital city of the Medes and the Persians, who beginning with Cyrus the Great, ruled the civilized world for almost two centuries, with one important exception.

*later Abraham

This is a rather curious account, in the 14th chapter of Genesis, of a military campaign known to Biblical historians as the “battle of four kings against five.” The chapter begins, “In the days of Amraphel king of Shinar, Arloch king of Ellasar, Chedorlaomer king of Elam and Tidal king of Goiim, these kings made war with Bera king of Sodom, Birsha king of Gomorrah, Shinab king of Admah, Shemedber, king of Zeboiim, and the king of Bela (that is, Zoar.)” We know today that Amraphel was Hammurabi, who emerged around 1,750 B.C. from the northern city of Babylon and with his famous code of law (uncovered at Susa) and his sword reigned over a united kingdom stretching from the Persian Gulf to the Khabar River. With Hammurabi, Babylonia’s history begins and Babylon is to become the arch-symbol of arrogance, luxury, sin and inequity for the remainder of the Bible, both Old and New Testaments. The four kings, in the Genesis version, overthrew the kings of Sodom and Gomorrah and other neighboring city states and carry off Lot, which is why the battle is included. (He will later be rescued by Abram and Sodom and Gomorrah consumed in fire and brimstone (possibly an earthquake; they are believed today to lie at the bottom of the Dead Sea).

Chedorlaomer is not otherwise known to history but it seems very likely an Elamite king did ally himself with Hammurabi at the time in an attack against the West. The name, incidentally, is good Elam, “Kudur-Lagamar.”

With Sumer vanquished, Elam seemed to enter its most powerful early period. Susa, already a city of 40,000 by 2,700 B.C. had at least 100,000 people by 2,000 B.C. and a new dynasty arose, styling themselves the “divine messengers” of Anzan and Susa. (Anzan being a nearby mountain city). The Elamites now worshipped the fertility goddess, Shala, and her consort Inshushinak, who gives present day Shush its name, and for many years were masters of Uruk and Babylon. But this imperial expansionism was checked by Hammurabi, although it took him 31 years to defeat Rim-Sin, his Elamite opponent. After an interregnum, a new “powerful empire” arose, but there were now only 48 agricultural settlements on the plain, half of the number that existed during Neolithic times. Modern Americans should note that as Susa and Elam rose in greatness there was a gradual decline in the number of farm villages until when Susa ruled the world as the Achaemenian capital there exists no trace of any agricultural settlements at all!

With the reign of Shilhak-Inshushinak in 1,165 to 1,151 B.C. Elam entered its “golden period,” although its monumental architecture was unable to surpass the vast mountainous temple of Dur Untashi (today known as Chogha Zanbil by the local Arabs, it means overturned basket) built by Ting Untash-Gal in 1,330 B.C. The biggest temple ever built in Mesopotamia and only completely unearthed eight years ago, it is a colossus as magnificent as the great pyramids of Egypt. During this apogee, which lasted for almost a century, Susa, as Elam’s capital city, ruled from the shore of the Persian Gulf, to the Tigris Valley to the Zagros range, almost the present boundaries of the Iranian province of Khuzestan.

But a new power was arising in the “land of Assur” of Genesis, north of Babylon, the Assyrian nation which won its independence around 1,500 B.C. and, aided by the horse and chariot and its peoples semi-barbarism, began expanding steadily northwards and southwards until at the height of their empire 9745-612 B.C. they came close to ruling the entire civilized area of the Middle East. Elam held out the longest, in a series of battles that began early in the sixth century and lasted more than fifty years. The campaigns between the Elamites and Assyrians went back and forth over decades, marked by internecine quarrels among the royal family, a revolution at Susa, extreme cruelty as captured generals were flayed alive and soldiers beaten to death, treachery and terror and two occupations of Susa by the chariot borne Assyrian forces. The war reached such bitter intensity and cruelty that Assurbanipal vowed to wipe Elam, the oldest enemy of Babylonia, off the face of the earth. The destruction of Elam and massacre of its entire population in 640 B.C.,* a holocaust that like such bloodbaths of contemporary times as the one in Indonesia in 1966 or during the partition of India in 1947, involved the deaths of nearly a million people, figures prominently in the Old Testament.

Political disaster had already struck the descendants of Abraham a century earlier when in 721 B.C. the Assyrians overwhelmed the kingdom of Israel and carried many leading families into exile. Judah was to meet the same fate in 586 B.C. when Babylon’s King Nebuchadnezzar captured and destroyed Jerusalem and deported a large part of the city’s population to Babylonia.

The failure of the Hebrew god, Yahweh, to prevent these disasters presented the heirs of the prophetic tradition with a new and formidable challenge. What was really God’s plan? By then the Yahweh known to Abraham, the god of the desert and of war, had undergone considerable change in the settled agricultural world of Palestine. The peasants of Canaan, while worshipping the God of Battles, increasingly were backsliding toward the old goddesses of fertility. Unlike the Sumerians’ Enlil, Yahweh’s worship stood in isolation, emphatically opposed to the nature worship of the fields. This created an acute internal contradiction in Hebrew society and led, during the eighth century B.C., to the rise of individual prophets, who felt themselves inspired by Yahweh to denounce religious corruption and appeal for a return to the old religion of the desert. Amos (ca. 750 B.C.) was the earliest of these literary prophets’, whose emergence also coincided with the simplification of language and writing into the relatively short alphabets that made it accessible to the ordinary man. Thereafter the prophetic tradition remained almost unbroken through the time of the author of the book of Daniel (150 B.C.), that of Jesus of Nasareth and St. Paul and until the appearance of Mohammed and the writing of the Koran in the sixth century A.D., the last of the desert prophets to portray God as just but stern, demanding righteous conduct of men and punishing those who flouted his commandments.

Indeed, the whole history of the Hebrew, Christian and Moslem religions reflects the constant tension between the religious needs of the nomadic desert Bedouin, the settled peasant farmer and the urbane, sophisticated dweller in cities. It is interesting today to note that the only one of these three religions to really permeate the daily lives of its adherents in large numbers is Islam; and it represents a serious obstacle to the technological progress and modernization of the Middle East. The fusion of the teachings of Jesus with Greek philosophy and the Protestant Reformation of the Middle Ages that made it possible to couple piousness with making money is one of the major reasons for the rise of the West and its present cultural imposition on the rest of the world.

A very early, but crucial step, toward this development occurred during the sixth century B.C. when the prophets Ezekiel, Jeremiah and the second Isaiah boldly undertook, from their exile in Babylon, to justify the ways of God to man. They demanded a more rigorous obedience to the commands of Yahweh and attributed the sufferings of the Jews to a divine plan not only to restore Israel to glory after a period of punishment, but that the children of Israel would take their rightful place as a light to all humanity and establish justice to the ends of the earth. This universalism and new emotional tone giving hope of the establishment of the Kingdom of God on earth transformed Judaism from the cult of a Bedouin tribe, as it had been in the days of Abraham and Moses, into a law and doctrine claiming universal validity for itself and total error for all rivals. This conviction, and the magnificent poetry in which it was clothed, have become basic to our cultural inheritance and explains more than anything else why Judaism survived to transform the world. Moreover, an exiled people could worship God without the focus of the Temple in Jerusalem or a fixed territorial home, thus accommodating individualism as well as universalism and freeing religious beliefs for the first time from geographical localities, secular cultural environments or ways of life (whether herdsman, peasant or city dweller.)

*Some put this date at 645 B.C.

In this transformation of Judaism from a tribal cult to a world religion, Elam, both during its destruction in 640 B.C. and its rebirth a century later under Cyrus the Great, figured importantly. Thus, we have the Prophet Jeremiah predicting in eloquent poetry both its fall and renaissance:

“Thus says the Lord of hosts, ‘Behold, I will break the bow of Elam, the mainstay of their might, and I will bring upon Elam the four winds from the four quarters of heaven; and I will scatter them to all those winds; and there shall be no nation to which those driven out of Elam shall not come. I will terrify Elam before their enemies, and before those who will seek their life; I will bring evil upon them, my fierce anger,’ says the Lord. ‘I will send the sword after them, until I have consumed them; and I will set my throne in Elam and destroy their king and princes,’ says the Lord. ‘But in the latter days I will restore the fortunes of Elam.'”

The extraordinary power and vigor of the prophets is seen when we compare such verses with the spirit of disillusionment and flaccid cosmopolitanism of the times as expressed in the book of Ecclesiastes, the famous passage of which, ending in “if ever the silver cord is snapped, or ever the golden bowl be broken…. ” has previously been quoted. The Prophet Ezekiel took vivid relish in warning the great cities of the time of their fate under the Assyrians’ sword: “And the Babylonians came to her into the bed of love and defiled her with their lust…. Yet she increased her harlotry, remembering the days of her youth in the land of Egypt and doted on her paramours there, whome members were like those of asses, and whose issue was like that of horses…”

But Ezekiel’s description of Elam’s destruction is very moving, “Elam is there, and all her multitudes about her graves; all of them slain, fallen by the sword.”

One of the last great Elamite rulers sighed his texts: “I Shilkhak-in-Shushinak, son of Shutruk-Nakhunta, a valiant chief, for the blessing of my life, the blessing of the life of Nakhunta-Utu, my beloved wife, and the blessing of the life of our family,” and it is indeed sad to note that the Elamite civilization, which lasted four thousand years, was totally destroyed in a single month by the Assyrian troops and charioteers. They burned and sacked fourteen royal Elamite cities before attacking Susa itself. One of the first to fall was the great temple city of Dur Untashi, today known as Chogha Zanbil, which was completely vanquished and its population massacred. It was utterly abandoned and never again inhabited by man; gradually the dust and sand of the desert swept over its ruins and even the great temple, the biggest ever built by man and towering 165 feet in the sky, with its top, indeed “reaching into the heavens, to was buried by earth, not to be discovered until the 1930’s by a geologist looking for oil. The battle, in mid-640 BC, lasted 32 days. After Susa fell and its entire population was killed, the city was looted of treasures amassed over thousands of years in wars with Sumer, Akkad and Babylon. Thirty-two giant gold and silver idols were carried away and even the tombs of ancient heroes ransacked and their bones taken to Nineveh, where libations were offered, supposedly so their souls would awaken to taste the bitterness of Elam’s fall. Assurbanipal later wrote that the Elamites were massacred and crushed “like grasshoppers;” he ordered salt to be poured on the Susianan plain so that it would never again be fertile. As Assurbanipal wrote: “The dust of the city of Susa and the rest of the cities of Elam, I have taken it all away to the country of Assur. During a month and a day I have swept the land of Elam in all its width. I deprived the country of the passage of cattle and of sheep and of the sound of joyous music. I have allowed wild beasts, serpents, the animals of the desert and gazelles to occupy it.

It seemed, indeed, Elam was destined for the desolation described in the words of the second Isaiah:

No Arab shall pitch his tent there

No shepherd will make their flocks lie down there.

But wild beasts will lie down there

And its houses will be full of howling creatures,

There ostriches will dwell

And there satyrs will dance.

Hyenas will cry in its towers,

And jackals in its pleasant palaces.

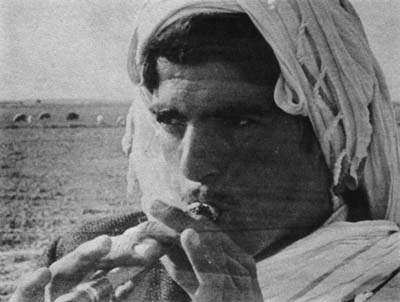

BEDOUIN

“…. while Jacob was a quiet man, dwelling in tents.”

The Book of Genesis, 25

One morning, two-thousand-six-hundred-and-seventy-two years later, an Arab shepherd named Jacob set out to graze his flock of sheep among the dunes and mounds of debris of the long abandoned temple city known to the local villagers as Chogha Zanbil. Here and there stars were still piercing through the ashen early morning sky. A wind was blowing from under a bank of cloud. Over the Karun River a mist was rolling high, piling against the dunes of the vast, vanished city and crawling into the cliffs along the riverbank like a grey, headless serpent. The far, east bank of the river, the sands, the marshy clumps of bulrushes and reeds, the dewy green shoots in the winter wheat fields, quivered with the ecstatic, chilly dawn. Beyond the eastern horizon stretched the Mesopotamian plain, perfectly flat, grassless, sand-poisoned and sterile. The winter rains had been late and few.

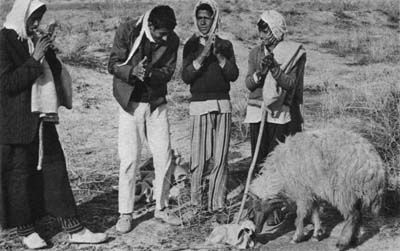

In the block Bedouin tent, Jacob had been the first to awake, rolling up his woolen quilt on the strip of carpeting where he slept. Buttoning the collar of his cross-stitched robe and wrapping a coarse woolen homespun cloak about his shoulders against the cold, he took his staff and his rod and went to feed the lambs. Already in the bramble bush enclosure that served as a sheepfold, Jacob could hear the ewes blatting for their offspring and the hungry lambs, kept inside an earthen hut at night against the winter cold, crying hungrily in high-pitched chorus in return. He brought the lambs to the ewes, carrying many who could not find their mothers and tottered back and forth until he lifted them into his arms, and the blatting died down to a hum of feeding and contentment. Deborah, a sister, ran past in her flapping black garments to milk the cows. Like all Bedouin women, her face was bare, disdaining Islam’s veil, Jacob stood for a moment, wondering if there would be yogurt for breakfast, then turned back to take the sheep past the village wheat fields into a sparse green pasture beyond.

A lone man, his head and body cloaked like Jacob’s against the bitter cold of the winter morning, called out in a gruff voice, “Watch your sheep that they don’t go into my wheat if you go into the dunes today.”

“Yes.” Jacob called back to him in his clear, strong voice. “My brother Husein is coming as well and we will take care.”

“Last night the dogs were barking, barking. Why?”

“I do not know. Perhaps men were coming, thieves or maybe hyenas or maybe dogs just barking for nothing. I do not know.”

Jacob shouted instructions to the sheep to keeper closer together and rest in place, “Aooooooeh, whsssss, whisss!” He whistled and threw his staff end over end into the air at several who had strayed too far ahead. “Brr-r-r-r-r! Br-r-r-r-r!”

After some moments his brother Karim came to relieve him so that Jacob could return to the encampment and take breakfast. Jacob was relieved and hurried back, running and breathing heavily.

His oldest brother Husein and Sharif, a young cousin who had come to buy a lamb, were already squatting around a fire of brushwood, breaking cold unleavened bread and washing it down with little glasses of steaming, sugary tea. Husein stirred the fire and ashes fell down, scattering sparks. An iron kettle sat in the coals and from time to time, passing the thimble-sized little tea glass from one to another, Husein would scald the glass and its saucer with hot water. Each one poured the tea into the saucer to cool and drank it down quickly, the hot liquid reviving them.

“If it rains I’m happy,” Husein said. A big, large-boned Arab, he had been head of the family since the death of his father ten years before, “If no rain I’m miserable. This is a very dry year. Usually the grass is a foot deep by now and covered with flowers.”

“Yesterday I passed two dead sheep in the dunes coming from Shush,” Sharif said. He had come the twenty miles by bicycle and planned to spend a few days with his relatives; although still only twenty-one, Sharif had left the Bedouin encampment ten years before to seek work in the Shush bazar. Now he had been called into the Persian army and had come so that he could leave a sheep behind with his wife in provision for hard days.

“One of the neighbors lost a ram two days ago, Starved to death,” Jacob said.

“You came through the dunes by bicycle, Sharif?” Husein grinned, “Many jackals, hyenas, wolves, leopards and foxes around those ruins.”

Sharif laughed. “I’ll hit them with my bicycle. I’ll take this knife and kill them.” The youth produced a large flick knife from his pocket. Its handle, enameled and decorated with stones of many colors had brass knuckle rings studded with little knobs. It looked a wicked instrument. Both Husein and Jacob held it, examining it admiringly.

Husein grinned. “You go through the dunes alone and all they’ll find in the morning is your jacket. Many hyenas at Chogha Zanbil. Big as a donkey.”

“I’m not afraid. I’d even go at night.”

“One herdsman here was asleep and a hyena bit him and that man went crazy after a few days,” Husein said. “A hyenas not dangerous by day but at night it can attack and eat two, three men.”

“Hyenas never ate any man in our village,” Jacob told Sharif. “We’ve got mostly wolves out here. Maybe if I’m alone with the flock and three or four hyenas came, I just let them take one sheep and go. This is a good knife, Sharif.”

“One day my wife’s sister said, ‘Give me your knife, Sharif, I have no knife to cut this chicken.’ Then I forgot to ask for it back and after two or three days I asked my wife, ‘Where is knife?’ ‘The knife is finished,’ she said. ‘I threw it away. In the river. I don’t know. Maybe you have fight with some man. Maybe get into trouble.’ I was very angry. I said, ‘Give me knife. Where is knife? It turned out she had only hid it.”

“Go to the flock now brother,” Husein said, hurrying Jacob back outside. As the shepherd left the tent, breaking into a jog across the fields, a querulous, frail but piercing voice called from the women’s quarter:

“Sharif! Shari-i-i-i-if! When is your father coming to see me?”

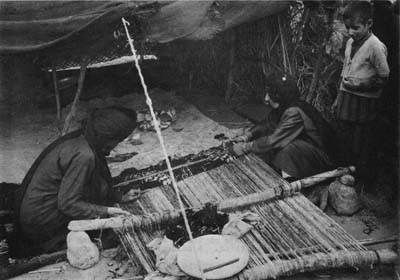

The two men entered the other end of the long black tent; here two younger women, Deborah and a red-haired girl whom Kazim had married the year before, were spinning wool on a spindle. Near them, seated in a corner and almost bent double was an old lady of extreme age, the shepherd’s mother. A tiny little woman, she was wrapped from head to foot in a grimy black shawl. From her face, weathered and wrinkled as a walnut, looked two piercing blue eyes; although filmed over with cataracts, the old lady still had enough vision to recognize her-young relative.

“Father’s an old man now,” Sharif told her. “It’s too cold for him to come in winter.

“Oh. Sharif, Sharif, come here,” the old lady cried, putting a trembling, claw-like hand on his shoulder as he bent down beside her. “I want to die. I am too old, too old. It is finished for me. You tell your father to come for a visit. I want to see him once more if there is time for me.”

“I will tell him. Maybe he will come. Maybe not.”

“Mother, give the horses water,” Husein ordered. When the old lady ignored him, Husein went out to attend to them himself.

“Oh, Sharif, Sharif!” The old lady’s voice rose in a plaintive wail. “I am almost dead. Before…today they give me bread; tomorrow I don’t know who will give me bread.”

Deborah, busy at the spindle, uttered an exclamation of disgust. “The old lady’s getting really bad,” she told Sharif, ignoring her mother’s presence. “You brought her a dress from Shush last night and now all morning she’s been saying you’re better than her own sons. She sits there and tells us to wash this and wash that. She was taking on bad last night because Kazim and Husein hadn’t come back from the gendarmerie.”

“I heard them come in late,” said Sharif, who tired from his journey had fallen asleep early. “What happened?”

Deborah explained that Kazim, the middle brother, had been arrested the afternoon before. A man from a nearby village had complained to the gendarmerie that Kazim had let his flock stray into his wheat field. The gendarmerie had come, eating a good meal and complaining the family had no cigarettes, and then they took Kazim away to the gendarmerie post until Husein returned with the flock at dusk and went to get him. The two brothers had walked home in the night, not reaching the encampment until almost midnight.

Somewhere, outside the tent, a woman screamed; a moment later Husein’s wife, the fourth woman member of the family, came staggering inside, holding one hand to her fore-head, which was bruised and bleeding.

“He hit me!” she wept. “Do you have a bandage, Sharif?”

“No, maybe you should go to Shush and see a doctor?”

“No,” she wiped her eyes with a grimy cloth. “I’ll tie it with a rag.”

Husein came in a moment later, “She forgot to tie up the cows and donkey last night and they got into the wheat bin,” he explained to Sharif, “They did not eat much but they could have died. Then how could we plow our wheat field?” He sat down and lit a cigarette apparently feeling justified. The fist he hit his wife with had two rings on the knuckles which had caused an ugly cut. There was an embarrassed silence for some moments. Sharif thought, if he is going to hit someone it should be these women for not washing the old lady. She looks as if she has not had a bath for some weeks. But he said nothing. His father had told him that when the shepherd’s mother was young, she was very strong and worked like a man. She had taken the sheep out all day, carried heavy tins of water, done everything. And now the family was prosperous with a herd of more than four hundred sheep and they left the old lady to sleep alone and she was almost blind. Maybe a hyena might come in some night and carry her off, Sharif thought to himself. Maybe her children want that a hyena should carry her off.