Gap Malheureux

January 2, 1970

To the island of Mauritius and the fishing settlements along its rocky northernmost extreme of Cap Malheureux dawn comes gently. The sky grays over the stars of the southern hemisphere and the pale, late moon grows insubstantial and thin as the fishermen leave their hats in the whispering filao trees and set sail into the lagoon. The moon still governs the tides and the ebb and flow of their lives; they have watched American astronauts exploring its surface on the village TV and there is an Apollo tracking station on the island. But moon-landings and space probes remain a perplexing fantasy, as mysterious an expression of God’s will as the doubling of the island’s population in the last fifteen years.

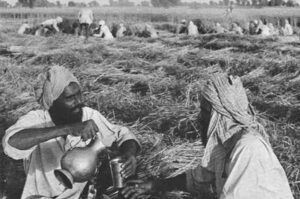

The fishermen’s pirogues skim across the green water, past meadows of pale sea grass and outcroppings of coral “n…..”heads. The tropical son from a perfect blue sky first reaches the island’s craggy volcanic peaks, fax, far distant, then moves down to blue hazy hills and the green slopes of sugar cane fields, a young green after the harvest. Just as the net is cast into the waves, a rim of blinding light comes over the Indian Ocean and the white foam at the reef glitters with reflected light; men’s shouts rise above the crash of surf against broken coral.

“Alle, alle, degage!”

“Hurry, Pa, quickly.”

“Let the plomb go. Ahhheee, Sylvestre, I’ll kill you. You are good for nothing but rum and stealing.”

With shoots, oaths, the rhythmic beating of sticks against halls, hisses, splashed gaffs and the strain of shoulders and backs, the net is drawn in, dripping with sea grass. Until two years ago, it would have been heavy with parrotfish, spiny-backed Cordonier, the dazzling reds and yellows of reef fish or a. big fifteen-pound carp. Then there were cries of “God is with us,” “We can catch fish today.”

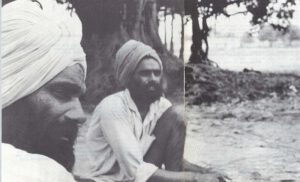

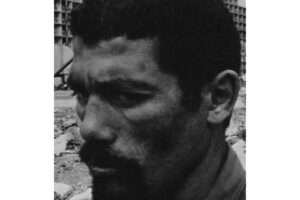

Nowadays there is usually only a bemused silence as the men see there are only a few small reef fish flopping in the bottom of the net. “Ah, Bon Dieu, ah mon maman,” the patron curses, wiping his face on a ragged slouch hat. The sleeves of his wet tricot are tight on bulging, ropy muscles and his hands are hard, with nails as thick and ridged as little clamshells after forty years of fishing. His eyes search the water, very bright blue eyes and piercing and set into a face deeply wrinkled and lined, but strong, and the color of polished mahogany. In their dark concentration there is something close to hopelessness.

For two years now the lagoon around the island has been depleted of fish. With not enough work in the towns or sugar fields, the young men take to the sea. They hunt fish everywhere in the lagoon, with nets, lines, bamboo cages, or, risking sharks and barracuda, underwater with spears and harpoon guns or, risking imprisonment, at night with dynamite. Now if a patron is lucky, a crew of sixteen men most share earnings from day’s catch of twenty pounds. Three years ago it would have been a hundred pounds and the sea yielded a decent living.

A command is shouted, “To the rampart where the foam is,” and the patron busies himself with the rigging as the small fleet of pirogues sets sail once more. But he watches, secretly, the hardening faces of his men and tells a. visitor the young ones are beginning to speak of revolution and the old of starvation and apocalypse.

The island of Mauritius, just north of the Tropic of Capricorn, is small, thirty-eight by twenty-nine miles, about one-tenth the size of New Jersey. It is an isolated speck in the Indian Ocean, really, 2,300 miles from Capetown, 2,000 miles from Colombo, 2,300 miles from Aden and 3,200 miles from Freemantle. On this tiny island are crammed over, 850,000 people, increasing at a rate of over 3 per cent per annum. At this rate it is estimated there will be well over 1.4 million inhabitants in twelve more years and nearly three million by the end of the century. The available work force has doubled in 15 years and already one man in three in unemployed. The reason does not lie in higher birth rates. It simply reflects a sodden, cataclysmic fall in the death rate since DDT completely eradicated malaria in 1950.

The problem of expanding or diversifying the economy to support move people is acute. It is entirely based on sugar, grown on 90 per cent of the island’s rocky but arable soil. Sugar provides 98 per cent of exports bat employs less than 60,000 men the year round. Britain buys 380,000 tons of the island’s yearly production of around 650,000 tons of sugar at a subsidized price nearly 150 per cent higher than the world price, saving the economy from total rain; it also supplies $6 million a year to help pay for the imports of floor and rice on which the Mauritians survive. Aside from a lack of land, capital and natural resources, the isolation of Mauritius from world markets means that savings in cheap labor may be cancelled out by transport costs.

Immigration, an obvious solution, has been frustrated by the unwillingness of most countries to accept any but the fair-skinned, highly educated elite on which the economy most depends. Madagascar, the great underdeveloped and under populated island only 500 miles away and inhabited by Malays, Africans end French, has steadfastly refused to consider the immigration of Mauritians.

For, unlike other over-populated islands such as Fiji or Bali, Mauritius is multi-racial end culturally diverse, a society composed of the white descendents of 18th century French colonists and pirates, their former Creole slaves of mixed French and African blood, Chinese and Arab traders and Hindus and Moslems whose great-grandfathers were imported as indentured cane workers. Today each of the five races retains its own culture, language and religion; as the standard of living has declined the past three years, the danger of communal and racial conflict has increased. Just before Britain granted Mauritius its independence in March, 1968, more than thirty persons were hacked to death in riots in Port Louis, the only harbor and capital city. The savagery traumatized the island and no one has forgotten it.

Present condition: Critical, according to the World Bank’s new population division, which describes Mauritius as “experiencing the first true Malthusian breakdown.”

Malthusian breakdown? The phrase may invite skepticism. With American agriculture turned down to a very low level of production, the Western Europeans debating how farm surpluses and incomes are the real block to unity and India, even in the aftermath of two failed monsoons, talking about the so-called “green revolution” in seeds and fertilizer bringing “self-sufficiency in just a few years,” the idea of a Malthusian crisis anywhere in the world may not sound too plausible. Especially on an island no one ever heard of. Some sophisticated Mauritians fear, probably rightly, that their problem will be viewed simply as an economic oddity that will eventually produce a political crisis meriting the world’s attention.

Yet in recent months there has been enough rethinking on the global population problem and redefinition of what is meant by a, Malthusian crisis; to give the plight of Mauritius some added relevancy. This is the concern that~, more than the threat of global famine, the combined problems of too many people, too few jobs, too little capital, stagnant or one-crop farming, high cost industry, small markets and big technologies are starting to outstrip the capacity of many governments to govern. The furiously multiplying fishermen of Cap Malheureux, as they catch every last fish in their lagoon, are not blaming their unemployed sons for surviving. They very naturally blame their government. “Vampires. Ali Baba and his forty thieves.” one hears the fishermen say. “Our children have no bread but the ministers are eating gold and diamonds. When the revolt comes, the people will walk on blood.” Smaller than Trinidad, more racially varied than Hawaii, Mauritius may present: in microcosm the social explosiveness ahead in may countries in the overpopulated seventies.

Mauritius first caught the attention of Western development economists 10 years ago with the publication of studies by R.M. Titmuss, a demographer, and J.E. Meade, an economist, both of the London School of Economics, Both found the island’s population growth was outstrip-ping its economic resources and warned of “a catastrophic situation soon” if productive employment was not raised 75 per cent, a policy of government-supported emigration adopted and some system of strict birth control enforced.

Meade concluded the island had few resources other than its land, the sea, the beaches and its people, whom he found unusually gifted and literate after 175 years of British role. He proposed diversifying agriculture, developing offshore fishing and taking steps to attract foreign investment and tourism. Titmuss proposed a number of disincentives for large families and an argent government-sponsored program to popularize family planning.

Neither program was adopted and in the intervening 10 years the population has risen another 100,000. Instead, with perhaps indecent haste, London announced in 1965 that now Mauritius “should be independent and take her place among the sovereign nations of the world.” Dr. Seewoosagur Ramgoolam, the grandson of a Hindu cane worker who had spent 14 years in London as a journalist and physician, led what he called “the struggle for independence against British imperialism.” He was knighted by Queen Elizabeth and last year became the first prime minister of an independent Mauritius.

Today with around 60,000 men employed by the sugar plantations and another 5,000 or so in industry, the government with 33,000 on its payrolls is the island’s second biggest employer. Nearly half of these are public relief workers who earn 30 cents a day three days a week, despite the added burden this imposes on the island’s $50,000,000 a year budget.

Since independence, which they opposed in favor of some form of West Indies-style association with Britain, the island’s Creoles, Moslems, Chinese and Franco-Mauritians, as the whites are called, have voiced fears of being overshadowed by the more populous Hindus. Under the inherited British political system, the Hindus were able to capture 45 out of 70 assembly seats two years ago in what amounted to a referendum for independence although they comprised only 46.5 per cent of the total electorate.

To set such fears at rest, or to demolish the opposition – one hears both versions – Ramgoolam formed a coalition government in November with the Creole opposition leader Gaetan Duval. Many responsible Mauritians hope this will forestall the drift among Hindus, Moslems, Chinese, Creoles and Franco-Mauritians forming corporate political groups along ethnic lines, heightening the danger of communal conflict. But there has been widespread resentment against both Ramgoolam and Duval for expanding the new coalition government to 21 ministries (a minister gets $600 a month, which to the average $100-a-year Mauritian seems an exorbitant amount), and for postponing new elections indefinitely. Charges of a sell-out have been widely raised against Duval, a darkly handsome, high-living young Creole lawyer, who, with his long hair and Carnaby Street outfits, is probably the world’s first hippie foreign minister. (One of his first acts as Nr. 2 man in the new government was to jet off to the Vale of Kashmir with an Indian princess.)

The coalition has also left the role of an opposition party open to a new radical force of lean, intense young school teachers, the Mouvement Mauricien Militant, which draw their inspiration from Frantz Fanon and Chairman Mao and their recruits from the ranks of the island’s 20,000 or so unemployed high school graduates. The MMM advocates a violent socialist revolution but~ has currently informed its followers it may take as long as five years to folly penetrate or organize all the Mauritian labor unions and the 2,800-man police and para-military force.

This winter the MMM claimed credit for dynamiting a water main but has been silent, over charges its members set fire to more than 5,000 acres of sugar cane, destroying nearly 2.5 per cent of the crop. Although the possession of fire arms is illegal in Mauritius, the Communist Chinese are said to be smuggling rifles in and it is widely assumed the Soviet Union, which maintains a 14-man embassy in the capital, is supplying, the MMM with organizational know-how and some financial support. Talk of a, bloody revolution is bandied about quite casually on the island. The unemployed youth whose visa to England has just been rejected is not untypical when he tells a visitor, “Now there is talk in the villages of rising up and killing ell the government leaders and the whites. But the leaders say, ‘The moment has not yet come.’ We will revenge the years of slavery by the capitalistes. I know it will destroy Mauritius but if I do not join when the time comes they will kill me.”

On the other side of the coin is the Franco-Mauritian mother, sitting in the drawing room of the chateau her family has owned for almost 200 years, who says, “My children are strange. They do not want to grow up.” Her husband observes that in a crisis the 13,000 whites on the island could muster only a small “strike force.” Asked if he really thought about such things, his wife replied for him, “I think about them, every minute of the day.”

Some of the more responsible Franco-Mauritians whose numbers have been held down by emigration (more than 50,000 to South Africa), have been trying to align the whites with the 210,000 Creoles, with whom they share French culture and Roman Catholicism. “Five years ago there was gulf between us,” says Gaetan de Chazal, a Yul Brynnerish assembly deputy. “I hated them and they hated me. But when we came down in the streets instead of just living in our castles we found they were just like us. Better than as in some respects.” Unfortunately, most of the Franco-Mauritians have indeed stayed in their castles or rather in their comfortable modern suburb of Curepipe atop the island’s misty central plateau, retaining the kind of former slave-owner racism probably found today only rarely in the American Deep South or in South -Africa. It tells something that blanche is considered something of an insult to most nonwhite Mauritians and is never used to describe Englishmen, Europeans or Americans.

Yet, despite its brooding present, there is a veiled torpor about Mauritius that is powerfully reminiscent of its palmy isolated days, when the island lay remote and mysterious far south in the Indian Ocean, only occasionally invigorated by a pirate raid, slave revolt or naval battle. In Port Louis, the capital city, there is still a last suggestion of piracy and the dark mysteries of Joseph Conrad; and though one is constantly reminded on television commercials (a community set in every village) that eight jet flights touch down here every week, it still feels faintly adventurous to be in Mauritius at all.

In Place D’Armes, where Queen Victoria glares stonily from her pedestal in front of the old Government House at freighters loading sugar in the harbor, you can observe a population that is a magnificent mongrel of all the races of man. Wanderers of all kinds settled the island: Dutch explorers who brought slaves from Madagascar, exiled courtiers of Louis XIV, runaway legionnaires from Morocco and Algeria, bourgeois colonists from the French provinces, prim English civil servants who ruled the island for 175 years but never stayed or settled down, bearded Moslem traders, paunchy Chinese hoteliers, Negroes from Abyssinia, Mozambique and Zanzibar, Hindus and Moslems from Bombay and Calcutta, and all that human flotsam that gets washed up with the driftwood of tropical seas.

The back streets of Port Louis are tortuous and twisting; there is a Moslem suq as forbidding as any in North Africa; a Chinese quarter with curved roof pagodas, posters of Mao’s thought and a, cold dead look in the eyes of merchants who will sell you anything. The Creole dockers’ quarter probably comes closest to the Conrad atmosphere and against the beat of African Sega drums and the sudden laughter from the rum shops, you might be stepping into The Rover or A Smile of Fortune, where Conrad used Mauritius as a setting. The island also inspired Bernardin de Saint-Pierre’s high-pitched 18th century romance, Paul et Virginie about the doomed love affair of a French girl and a Creole boy. (“Now I stay, I go, I leave, I die.” cries Virginie, forced to leave for France. “Maiden without virtue! I can resist your caresses but not your suffering.” She returns only to be shipwrecked and drowned at Cap Malheureux, washed ashore at Paul’s feet.)

Upon this romantic fabric, and despite a smattering, of cars and TV sets, surprisingly little of the fall-out of modernity has settled. Paul and Virginie have joined the extinct Dodo bird and Queen Elizabeth as subjects of Mauritian postage stamps and three neo-functional glass and concrete tourist hotels have been opened up to match a new neo-functional glass end concrete airport. A few enterprising tourists are in (535 Americans in 1968.) “Mission Impossible” runs with dubbed-in French dialogue every Monday night on TV, there are two ballet companies, a symphony orchestra and a score of amateur dramatic troupes. A few of the old French plantation houses have been debased by the times into banks, hotels or museums but many still serve traditional purposes. There is a Lions Club, a Boy Scout movement and some good modern restaurants; although if you ask for a martini, the waiter may reply, “Light or dark?”

If anything is going to save Mauritius it may well be legions of American tourists with fat American Express checkbooks. Oddly enough, Mauritius, with its compellingly beautiful landscapes and seascapes, its warm and luminous days, is probably one of the few places in the world where they would still get their money’s worth. For through it all, surviving even population, the old Conrad spirit – the undercurrent of chicanery and dark doings, the raggle taggle of foreigners spicing an already pungent atmosphere – has hauntingly, triumphantly survived.

The World Bank, since Robert McNamara has taken up the population dynamics of economic aid, may also come to the island’s rescue. The bank is currently negotiating with Prime Minister Ramgoolam to aid the government with a revolving fund for planned migration, tea development and technical training provided it adopts a sound program to curb population.

This too is easier said than done. After near riots when the government tried to adopt Titmuss’ recommendations: in 1965, Mauritius settled for two privately-run, but government, subsidized family planning organizations. One caters to the island’s 400,000 Hindus, 120,000 Moslems and 25,000 Chinese, selling the pill and intrauterine devices at low prices. The other, sponsored by the Roman Catholic church, promotes the rhythm method among young Creole couples. But the two organizations practice in fighting and propagandizing against each other’s methods, the Hindus saying the rhythm method is useless and the Catholics warning that the pill and IUD can cause cancer and other ills.

The bank wants the government to take over the entire effort and offer all three methods without pushing any particular one. As of now, only 16,000 of the island’s 120,000 married women in their reproductive years practice some form of birth control; the bank would like to see a target of 60,000 women enrolled by 1974.

The island’s Catholic bishop has agreed to go along with the proposal on an experimental basis. An unexpected obstacle has been Ramgoolam himself, who told an astonished population expert sent by the bank to develop an action program that he really felt Mauritius could turn into another Hong Kong and that he personally would like to see its population grow to as much as two million. (In practice, however the government discourages foreign private investment through restrictive labor, policies and high taxation. (Ramgoolam similarly startled a meeting of the International Monetary Fund some time ago by saying that since Russia, China and the United States all had nuclear arsenals and someday somebody was bound to use them, it might be best for Mauritius to stock up on survivors.)

Most Mauritians, in contrast, seem deeply alarmed about overpopulation and the steady decline in living standards, although among both the more illiterate sections of the Creole and Hindu populations there is more talk about God’s will than family planning. Asked about Rangoolam’s attitude, a veteran British observer commented, “I think he’s just a bloody optimist.” Then he added, after a pause, “What’s amazing is that Mauritius didn’t have a revolution five years ago. The Communists don’t have to do anything here. It’s a ripe fruit ready to fall.”

If Mauritius is going to attract the world’s attention to its plight, it will probably come when Ramgoolam goes through with his plans this month to grant, harbor facilities to Soviet “research vessels” in return for technical aid for Mauritian fishing industries. This would give the Russians their southernmost base yet athwart the sea lanes around the Cape of Good Hope. Warships of the U.S., British and South African navies have been calling at Port Louis with a new frequency in recent months; they may fear a Russian base athwart what has now become the chief trade route between Europe and Asia now that the Suez Canal is blocked.

In the meantime, ordinary life goes on. And once you get used to living with a sense of apocalypse, it is not the pre-revolutionary atmosphere but the peculiarity of the place itself that tells: the hush of the Indian Ocean dusk with the trade winds whispering through the filao trees, the waves crashing on the reef, the weathered face of a Creole fishermen, heading his pirogue into the bright loveliness of the moonlit lagoon, lighting a cigarette and grinning, “Perhaps, my brother, God is with as today and we can catch fish.”

Received in New York on January 7, 1970.

©1970 Richard Critchfield

Mr. Richard Critchfield is an Alicia Patterson Fund award winner on leave from the Washington Evening Star, Washington, D.C. This article may be published with credit to Mr. Critchfield, the Washington Star and the Alicia Patterson Fund.