A study in four parts of the human impact of the new seeds and methods of cultivation in Ghungrali-Rajputan, a prosperous farming village on the Punjab Plain in Northwest India

Part Two: The Seeds Of Change

Green Revolution

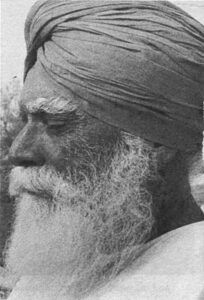

Everyone said Basant Singh, the richest farmer in Ghungrali, was as hard as flint. While the other villagers might fritter away their days in gossip, drink, chasing women, petty quarrels and the like, it was said Basant Singh’s thoughts never strayed from economy of operations and returns. In matters relating to religion, politics, morality and money, he was harsh and relentless and kept a strict watch, not only over himself and his family but over his servants, laborers and acquaintances and, indeed, the whole village. God forbid that anyone should go into his office off the veranda without being announced by someone.

This office was like Basant Singh himself and, needless to say, was the only one in the village. Straight-backed wooden chairs stood at attention in rows along two walls below framed photographs of the office’s occupant with a former national minister of agriculture, the vice-chancellor and senior faculty of the state agricultural university, visiting foreign technicians and other such luminaries. At one end of the office, directly confronting a visitor as he entered the dim, musty room, blinking from the sunlight, was a large desk with neat stacks of files, documents and government periodicals announcing the latest technological advances in agriculture. Against the wall file cabinets held a formidable collection of bound records, for Basant Singh kept not only detailed accounts of all his own operations but those of all the village farmers as well.

Every conceivable item relating to the cost of production on his own fifty-four acres was there, including amortization of everything that was amortizable, and not excluding food for the seventeen members of his family, four permanent laborers and food for twenty daily workers during the peak of the harvest season. The last item, “Return to Management.” summed up the 1968-69 season: it showed a net income of 1,600 rupees per acre. The figure was made up of sales of wheat seed which commanded a price of one hundred and eighty rupees per quintal as against the market price of ordinary grain which ran at seventy-six rupees per quintal most of the year but fell to sixty-six just before the harvest. But had he devoted all his land to grain only as the principal crop, Basant Singh would explain, his net income per double-cropped acre would have amounted only to six hundred rupees.

Basant Singh did not need to tell his fellow villagers these facts; they all knew them by heart. Basant Singh had started life as a poor man, with only two acres in the old village in Pakistan; his rise and accumulation of wealth in recent years had been so phenomenal as to make him an almost legendary figure in the region. He and his older brother had married girls who inherited land from their fathers. During the land consolidation in Ghungrali in the early fifties the government sought to build a canal through their land and his wife was awarded ten thousand rupees for the right of way title. Somehow Basant Singh got hold of the government franchise for wholesale liquor sales in the village and gradually his fortune began to grow. But it’s real source came from the introduction of the new high yielding varieties of wheat. They were first sold by Dilbagh Singh Atwal, a wheat breeder and his brother, who marketed their seed crop at two to five rupees a kilo for a return of seventy thousand rupees. This was in 1964. The following year Basant, profiting God knows how from his ties with the university end agriculture ministries, planted the first of the new seeds in Ghungrali and at the harvest sold three hundred quintals of seed from the dwarfed Mexican wheat for three rupees a kilo for a profit of fifty thousand rupees. The next year he planted another new variety, PV 18 and sold the seeds, again at three rupees a kilo, from four acres for a profit of 70,000 rupees. Khalyan Sona, the most popular variety in Ghungrali, came the next year and when the state government bought his seed crop at the rate of 1.9 rupees a kilo, Basant Singh made another 90,000 rupees. This year he had sown thirteen acres in a still newer variety, triple dwarf. His neighbors judged he would not harvest less than twenty quintals per acre which he could sell, at a minimum, for one hundred and fifty rupees per quintal, making double the profits of the farmers around him.

Basant Singh’s neighbors might be envious, but they had learned to listen when he told them that the stepping up of investment from six hundred rupees an acre for a net return of eight hundred would be counter-productive unless even newer varieties were developed with a capacity to sustain larger application of fertilizer. They listened when he said that from 1953 to the previous year, grain prices had risen only thirteen to seventeen rupees per maund (one maund=82 pounds) whereas the cost of inputs had risen five times.

“In fact,” he would tell them, “the profit we get from our farm production has diminished and we have to cut back in investment. The new seeds can double production. But somebody hears about it in Delhi and they reduce the price of grain. Whenever I get a chance, I’ll sell my land. There’s no money in farming. Business, industry, that’s the place to be. Wheat prices may be over sixteen thousand rupees an acre but the yield doesn’t give you the interest that a sixteen thousand rupee investment does.” To the chosen, Basant Singh would bring out his documents and charts to prove his point. “In fact, when we calculate at the end that for desi wheat we needed only five waterings and only half as much fertilizer and for these new varieties, eight to ten waterings and double the fertilizer, we see we have to spend double but don’t get anywhere in terms of profit. Ah, the nation increases its food production all right. But I’m not talking about the nation, but the interests of the ordinary farmer.”

Because of his reputation and his careful records, Basant Singh was sometimes visited by government officials and economists; since a car was a rarity in the village, the sight of one approaching usually meant Basant Singh was having visitors. Although he was pleased by the attention, Basant Singh would snort, “These foreign experts. They ask the shortest possible questions and would the shortest possible answers. Those World Bank people came out here to ask if I was still selling grains for seeds. They asked, ‘Will you sell seed grain in the future?’ I told them, ‘Every variety is out now. There’s not much scope.’ This year it seems half the village is growing triple dwarf, God knows where they got the seeds. The trouble with as Punjabis, I shouldn’t say this, is that everyone is dishonest.”

The village viewed Basant Singh with a mixture of envy, respect and grudging admiration except for his feelings about the Harijans. Most of his fellow farmers took the attitude of old Pritam Singh, who would say, “Basant Singh has really done good for this village.” But Pritam would also add, “He’s too hot tempered with the Harijans. He has been very unfair to them.”

For, preoccupied as he was with economy of operations and profit, Basant Singh did not concern himself with the impact of the new seeds and methods on the village Harijans, who worked as agricultural laborers and sharecroppers. What to others was a deepening social crisis for the lower castes as the traditional village jajmani system of exchanging labor in return for a fixed part of the crop gradually gave way to a money economy, (The so-called ‘green revolution’ of hybrids and fertilizer has already turned the Philippines from half a century of rice importing into a potential rice exporter. Wheat production in Pakistan is 60 per cent higher than its previous annual average since the mid-1960s. In India there is talk, even in the aftermath of two failed monsoons, of self-sufficiency in grain. A chance therefore exists that the critical increase in agricultural productivity which preceded industrialization in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries is now belatedly appearing all through the developing continents.) was dismissed by Basant Singh as “the labor problem.” He looked forward to seeing the modern agricultural version of the trinity – the tractor, the combine and electric power – displacing hired labor to a vanishing point and, indeed, had placed an order to buy one of the first twenty combines in the Punjab, or in all of India for that matter. Basant Singh didn’t see this happening too soon, however. When government or foreign experts expressed concern over the development of widespread rural unemployment in the Punjab, he would reassure them that the economies of labor he received from his tractor and other modern machines were more than offset by double cropping, weeding and the need to harvest the new dwarf wheat as quickly as possible to avoid shattering and get the threshing done before the rains set in. According to his figures, he said, he was employing10 to 20 per cent more laborers, depending upon the season, than before the new seeds were introduced.

“Rightly handled, this revolutionary change can be used to encourage a far more creative and human pattern of urbanization. Of course, such an outcome demands policy, not drift. There are choices to be made. Larger harvests and greater incomes may well be directly engrossed by feudal owners or enterprising farmers. Large holdings can be mechanized, smaller farms consolidated, increasing the gains of the fortunate and raining the little man. As in east Prussia in the nineteenth century a vast region almost devoid of small diversified urban centers can be handed over to mass production largely for export on vast estates in which both direction and income are concentrated in a. single hand.

“Or, as in Denmark at a comparable period, small farmers can be given the benefits of credit and education, achieve the advantages of scale through cooperation and use a network of small market towns and townships where storage, administration, high schools and extension headquarters help to build up a lively population which in turn attracts traders and light industry.

“There are thus decisions to be taken over and above the decision to modernize the farms. Even if, on strict economic analysis, east Prussia’s agricultural growth rate may have had the edge over Denmark which is doubtful – the social cost in terms of Junker dominance, lack of local diversification, big-city migration and the exploitation of Slav newcomers added up to a burden of which two world wars may have been part of the price. And even in economic terms it is not enough to produce the grain. It must be sold. Empty countrysides and unemployed cities do not add up to an expanding market. And if, as in many parts of Latin America, the feudal classes tend to salt away their savings in Switzerland, an agricultural revolution could occur and, like so many previous innovations in Latin America, drain all its gains into too narrow and too static a group for economic diversification to take hold.

“In short, if the new possibilities in farming are left to traditional channels or simply to the unregulated play of the market, the chances are that they will play no create part in easing the crisis of the cities….”

From “The Cities that Came Too Soon,” by

Barbara Ward, in the Economist

December 6,1979

“The main economic facts about agriculture are: (a) over 60 per cent of the labor force of the world is at present engaged at it, although with modern production methods an advanced country can more than feed itself with between 5 and 10 per cent of its labor in agriculture; (b) the stage when agricultural supply becomes almost fantastically elastic – so that production expands and new methods of cultivation are adopted in response to greater price incentives – tends to come quite suddenly, at a particular point of a country’s educational and economic and social development. European and North American agriculture reached this stage some time ago, which is why their ministries of agriculture who originally thought that their job was to keep farm production up – have found themselves snowed under with gluts. It had always been clear that it was only a matter of time before some underdeveloped countries followed them.

“There are now strong signs that this point of ‘green revolution’ has been reached in many poor countries during the second half of the 1960’s. The trail was blazed by Mexico and the Philippines early in the decade; but in the past few years farmers in India, Pakistan, Ceylon and parts of South America have shown a great new willingness to move to more productive methods if good prices give them an incentive. During the 1970’s this process is likely to grow much stronger, and these countries will find that they do not need on the land more than a small proportion of those who work there now. And that, of course, is the problem. The flow to the towns is already a major trouble in the poor countries of the world. In the 1970’s it is liable to become an uncontrollable flood, and threaten real, red, raw, urban revolution….”

From “Into the Seventies; Green Revolution or Red?”

The Economist, December 27, 1969

The jajmani system was rooted in caste and although Sikh religious teachings strongly condemned the Hindu caste system which divided society into racial compartments and excluded Harijans or untouchables from its benefits, it was still practiced in Ghungrali and all the other villages of the Punjab. All Sikhs in the village, including the Harijans, both the Chamars and the Mazhbis, had access to the Gurdwara where they sat together and on religious festivals, ate together.

There, with some irony, they heard such teachings as that of Angad, the second Guru:

The Hindus say there are four castes

But they are all of one seed.

‘Tis like the clay of which pots are made

In diverse shapes and forms – yet the clay is the same

So are the bodies of men made of five elements

How can one amongst them be high and another low?

How, indeed? But both the Chamars and Mazhbis suffered constant discrimination and there was no intermarriage between them and the Jats or even between the two Harijan sub-castes. Why the caste system endured so tenaciously in the Punjab, where few other Hindu beliefs were accepted, seemed to be explained partly by race and partly by economics.

The Jats of the Punjab, who today are divided by religion and language into the Urdu-speaking Moslems of West Pakistan, the Hindi-speaking Hindus of the Indian state of Haryana and the Punjabi-speaking Sikhs of Punjab proper, were relative late-comers to India. An ancient ethnic group of Indo-Scythian origin, they did not migrate to northern India until the time of Julius Caesar and Christ. In contrast the Mazhbis, dark-skinned and short of stature, were descended from India’s aboriginal Dravidians and the Chamars although many had Jat, blood from the ancient peoples of the Indus Valley who, at Mohenjo-daro and Harappa, had full-blown civilizations along the five rivers of the Punjab (which literally means “Five Rivers”) as early as 2,500 B.C. The Jats, taller, fair skinned and of strong aquiline features, came from Scythian ancestors who first appeared as barbarians from the steppes of present-day Russia around 600 B.C., when they joined with the Medes in bringing the Assyrian empire to rain. In 512 B.C., the Persian Darius waged a European campaign against them; by then they had created a powerful, if loosely consolidated “empire” in southern Russia, and expanded their power as far west as the plain of Hungary. Like their Persian kinsmen and counterparts, and as they were to do in the Punjab centuries later, the Scythians imposed themselves as a ruling stratum upon earlier inhabitants. But unlike the Persians, the Scythians themselves continued to live a semi nomadic life under tribal discipline and had not yet turned to farming. There is evidence, though, that some of the upper classes of the Scythians were able to indulge their appetite for Greek wine, oil and other products by compelling their subjects to produce wheat which the Greeks needed at home. Moreover, in time, at least some of the noble Scythians acquired a veneer of Greek culture. But mostly the Scythians remained a nomadic people of the great Eurasian steppes, displacing less warlike rivals, winning richer pastures for their flocks, or establishing themselves as overlords of settled agricultural populations. It was not until the height of the Roman empire that the Kushans of Mongol race were able to drive the partially Hellenized Scythians from the rich pasture and wheat lands of southern Russia and the lower Danube and they began their great migration to the Punjab, plain of northwest India, seizing some villages within fifteen miles of the present-day Indian capital of Delhi less than a hundred years ago!

Initially the descendants of the Scythians, who became Indianized into Jats, considered the southeastern part of the Punjab as their Indian homeland and it was not until the collapse of the Mughal empire in the l9th century under the pressure of British colonialism that the Jats spread to the more fertile areas further north and occupied the whole of the Punjab’s best farming country, where they have remained ever since. This history helps explain why the Jats, with their rough warrior spirit, glorying unabashedly in the strength of arms, in the destruction of their foes and the number of their cattle, never came under the domination of the priests and holy men of the Gangetic plain who succeeded elsewhere in setting the whole spiritual, life-negating tone of Indian intellectual life. Nor was it surprising in Ghungrali to find Hindu philosophical beliefs such as transmigration, the existence of an all-embracing holy spirit or atman and punishments and rewards for ethical behavior much stronger among the Mazhbis than the Chamars and much stronger among the Chamars than the Jats, as we shall see later.

Thus Ghungrali’s caste system was perpetuated, not so much from Hindu influence from the sooth, but because quite different blood flowed in the veins of the Jats, Chamars and Mazhbis. It was no accident that physically and in their mental make-up, the Jats had more in common with the Cossacks of the Ukraine than their fellow Indians.

The second reason for the caste system in Ghungrali was economic; the Harijans provided a source of cheap labor. After 1947, sixty-five Jat families, were allotted land in Ghungrali proportionately to their previous holdings in Pakistan and chose to live there. In addition twelve more Jat families received land but chose to remain in other villages. In the village there were also twenty-six more Jat families who were not farmers or land owners, such as the barber, a retired military doctor and men of other non-farming occupations. But there were also fifteen families of weavers, fifteen families of shoemakers, three black-smith, carpenters, and one hundred and one families of agricultural laborers, of whom most were Chamars but a small minority were Mazhbis. The Chamars, traditionally the leather-working caste, were better off economically than the Mazhbis, who, small in number in Ghungrali, were by caste sweepers who mostly made their living cleaning barns and making cow dung cakes for fuel.

Thus Ghungrali was mainly divided into two groups: the ninety-one families of Jats and the one hundred and sixty families of Harijans, the vast majority of whom were Chamars.

Together this little community of 251 families, comprising 217 houses and 1,415 men, women and children farmed 1,635 acres of land out of which about 1,500 was cultivated, irrigated and sown. (Before the 1947 massacre, Ghungrali had 900 houses, and a population of about 4,000 Moslems and 1,000 Sikh Harijans)

Wheat, grown from November through April, was the main crop, planted on 1,130 acres. Also, during the rabi or winter season, Ghungrali had 110 acres of sugar cane and the rest of the land in oats and grass for fodder. In late May, the kharif or summer crop was sown: 100 acres of oil seed, 350 acres of hybrid maize, 313 acres of cotton and 192 acres of ground nut.

The first major transformation of agriculture in Ghungrali had come with the installation of the first tube well in the village in 1953; water was everything in the Punjab, with it you could turn a desert into a garden. The next year there were 31; in 1957, 46; in 1962, 66; in 1963, 71; in 1964, 76; in 1967, 81; in 1968, 88; and by 1970, 90. All but 11 of the wells were run by electricity; those whose centrifugal pumps still depended on diesel engines included the farms of Charan and his neighbors, Sarvan Singh and Pritam Singh. They had not applied originally since their land lay near a canal which brought snow from the Himalayas at cheaper rates; now this source was drying up and nine of the 11 farmers had applied for electricity and had been promised it for 1971; the government would install electricity at the cost of 860 rupees for one horsepower; any charges over that a farmer had to bear himself and many complained a small bribe of 100 or 200 rupees was also required to get action. In the village in mid-1970 were 51 electric motors and 35 diesel engines. None of the old Persian wheels were in use but stood like relics of a by-gone age.

As mentioned Basant Singh had planted the first four acres of new high yielding wheat seeds in the winter of 1965-66. The next year all 65 families planted seed plots on an experimental basis. The year after that every single acre of wheat land in Ghungrali was planted in the new varieties and the old desi variety of wheat totally abandoned. Charan’s experience was typical. He had two acres of Mexican PV 18 sown on 1.4 acres in 1966-67. The next year Khalyan Sona on two acres and PV 18 on twelve. The third year, one acre of 227 and the rest in Khalyan. The fourth year, one acre of RR21 and all the rest in 227 and in 1970, all in RR21 except for half an acre of “Triple Dwarf” with which he planned to sow all his fields in future years. Since the dwarf wheats tended to lose their high-yielding characteristics over a three-year period and revert back to taller, more ordinary strains, Charan’s hope was that new varieties would continue to be perfected and introduced by the universities and government research stations and Sadhu Singh’s days were often spent keeping up contacts with such places and carrying on reconnaissance as to how newer seeds might be obtained.

Always in the forefront, Basant Singh bought Ghungrali’s first. tractor in 1962; in 1964 there were eight; in 1966, ten; in 1967 fourteen and by 1970, sixteen with over 20 applications for tractors on order from hard-pressed tractor manufacturers who in 1960 could not sell their small production.

In 1960, Ghungrali’s total fertilizer consumption had been for 40 tons of nitrogen; by 1968 the village was consuming 415.2 tons of nitrogenous fertilizer, 150 tons of phosphate, six tons of potash and 1.8 tons of sparten. Insecticide was used on 120 acres, of maize, 145 acres of sugar cane, 250 acres of cotton, 150 acres of wheat and 45 acres of groundnut. Pesticides were not used at all. As Charan explained it, “The rats here may have their holes in my field but they will go two or three acres away to eat sugar cane on another man’s field. If this man uses pesticides and I don’t. they have no meaning. The same for insecticides.”

Credit had been provided by the Indian government with 77,000 rupees advanced in 1967-68 for thirty pumping sets. Bank loans issued by a state Land Mortgage Bank began in 1968. A village Cooperative Agricultural Service Society with 114 members had advanced credit of 30,000 rupees for fertilizer during the kharif season of 1967 and 63,400 rupees during the rabi season of 1967/68. By 1970, it had loaned Ghungrali’s farmers 170,000 rupees with 120,000 of these recovered and 50,000 still outstanding. The Cooperative Society, which was under pressure to tighten up, was considering imposing a super-interest on its normal rate of 9 per cent. Said Mohinder Singh, its new general secretary, who was known in the village as One-Eye, “If somebody doesn’t pay as after the rabi crop is cut, we can confiscate his property and land.” One-Eye, however, was seldom taken seriously since he habitually dealt in hyperbole.

Thus in the past seventeen years, but especially with the introduction of the new seeds five years before, Ghungrali’s agriculture had been revolutionized. Owner-farmers with enough, land like Basant Singh, had made money hand over fist and the bigger the farm the more they made. Of the burden of taxation, there was none to speak of, a mere 3.10 rupees a year per acre of sugar cane, cotton and chilies and 4.20 per acre a year on other crops. There was talk of the state government imposing a new property tax law on those with investments over 150,000 rupees, but Basant Singh, who should have known, dismissed it as idle speculation.

But the condition of small farmers, forced to keep up with the changes, was much bleaker and some, like One-Eye, were rumored to be facing bankruptcy. So far the cooperative credit system had failed to help them breach the gap imposed by their lack of resources.

As the former sarpanch and one of the wisest men in the villages, Surjit Singh, said, “In other countries, with the revolution of agriculture, the rich got richer and the poor got poorer. The same thing is happening in Ghungrali. There are two or three houses in this village, Basant Singh, Sukhdev Singh, Jarnail Singh, who have gotten richer and richer the past five years. And they give loans to the poor farmers on very high interest. Five rupees on a hundred rupees a month. Not all, but a few people have mortgage eight to ten acres out of 25. Now they won’t be able to pay it back, and they’ll have to mortgage some more.

“People are afraid of the land mortgage banks because they’re very strict. If you don’t repay them, they’ll put your land up for auction. With individual borrowing from a fellow villager, at least you can still farm. The farmer in Ghungrali, his standard of living has risen all right, but he’s been increasingly in, debt these past; six or seven years.” Surgit believed only Punjab State’s land ceiling of 30 acres per family prevented men like Basant Singh from becoming great land owners at the expense of the small village farmers. Even then, if one had a big enough family and each member held a 30-acre title in his name, there were ways to get around this limitation.

And, indeed, Basant Singh, although an elder brother held title to half his land, already farmed 54 acres.

Charan, with fifteen acres and renting three more, fell just about in the middle economically of Ghungrali’s 65 Jat farming families. With nine family members, himself and his wife, Sadhu Singh and the Old Lady, Charan’s five children, the teenage students Suka and Kulwant and three small ones, Kuldip, Roda and the only girl, Rani, plus Peloo and a daily wage laborer, Charan had eleven persons to feed to say nothing of the family’s constant flow of guests and relatives.

During the rabi season, he raised 14 acres of wheat which he sold at 18 quintals per acre for 76 rupees a quintal the year before; (A quintal equals 100 kilograms. A maund equals 82 pounds. Both systems are used in Ghungrali which is converting to the metric system; hence the confusion.) in 1970 the price of wheat had dropped to 66 rupees during the harvest. Grass and oats were raised to feed his cattle: six buffaloes, two bullocks, one cow, two female calves and six small male calves, plus his dog Jubru, a Dalmatian.

During the kharif season, he raised 12 quintals of cotton which he sold for136 rupees per quintal; 56 quintals of maize sold at the rate of 52 rupees per quintal and 14 quintals of sugar almost all of which was consumed at home and 7 quintals of mustard oil seeds.

His land had spiraled in value in recent years and was now worth a minimum of 15,000 rupees an acre. (While the legal rate of a rupee is 7.50 to an American dollar in terms of real value it is more sensible to think of a rupee as worth about an American dollar.) Four acres had been mortgaged to the Land Mortgage Blank the previous year for a 15,000 rupee loan to build his cattle yard and sheds; it would have to be repaid at 9 per cent interest over the next ten years with the first installment doe in June, 1970. Charan and his father had also borrowed 1,200 rupees from the Cooperative Society for the previous year’s kharif crop which had been repaid. He presently owed 2,000 rupees for the 1969-70 wheat crop.

“My principal,” Charan said, “is that if I take a loan for fertilizer in the kharif season I must repay it in rabi. Not all the villagers repay the Cooperative Society. Some owe as much as 10,000 rupees and a few haven’t paid anything back for five years. In the village, a few farmers follow my example, a few take no loans at all. But the majority are getting deeper and deeper in debt. The real problem of indebtedness is with those who take a loan for fertilizer but use the money instead for a marriage. Since they haven’t used the fertilizer, their crops are poor and then they are really in trouble. It’s a question of good management. In Ghungrali you can do well with ten acres and have a thresher, tubewell, three bullocks, tractor and two laborers if you manage well. Some do.”

Finding themselves in a money economy very abruptly after centuries of traditional agriculture, the Jats in the village all have been forced to search for economy in operation. As Surgit Singh described it, “The small farmers can keep up only if they are given some government, subsidy. Those who have between fifteen and twenty acres or less will sink otherwise. Inputs have risen in cost much faster than wheat prices and the actual profit we are getting from agriculture is diminishing and we have to cut back on expenses and investment.

Basant Singh would say, “The small farmers will lose their lands. Looking to the future, the prosperity we see in the village now is illusory. The reality for a Jat family with fifteen or twenty acres is that they will have to get more and more loans to farm and educate their children. This picture will become clearer in three more years. In 1973, many of the mortgages come due. I foresee either government subsidies for the small farmer or direct government control. With this land ceiling of thirty acres you can’t practice economies of scale. Now the government is not yet thinking in these terms. With all this talk of a green revolution, the government thinks wherever it finds flesh on the farmer’s bones, they have to pick it.”

In the search to economize, one obvious place to many of the Jats is in the cost of labor. In Ghungrali, this was especially true of the rich farmers like Basant Singh, who wanted to solve their “labor problem” by mechanizing as soon as possible, and poor farmers like One-Eye, who with only four acres out of which only two and a half were planted in money-making wheat, was going broke anyway. This led to a strange alliance of very rich and very poor Jats against the Harijans. For Harijan labor amounted to half the input and expenses on every Jat’s farm in the village.

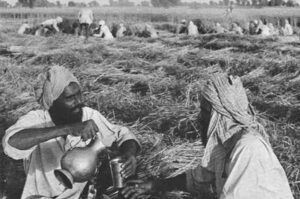

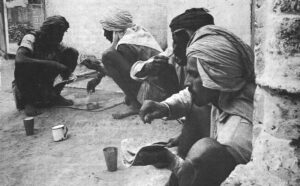

For centuries, under the old jajmani system, a lower caste member received a fixed part of the crop in return for his labor, a system, codified down the years through custom and tradition. Men like Basant Singh and One-Eye wanted to abolish this system. The previous August, the rich farmers such as Basant Singh, while standing in the background, had created a 13-member committee composed of such men as One-Eye, but including a few of the more prosperous farmers as well, to negotiate the terms of daily wages with the Mazhbis and Chamars. While a daily wage of five rupees a day plus all meals was standard throughout Ludhiana district, this committee had succeeded in negotiating a settlement in Ghungrali for four rupees a day without breakfast or morning tea, which broke a tradition going back as far as anybody could remember. This allowed Basant Singh to pay only four rupees to his laborers on the ground there was a general village settlement. The Mazhbis and Chamars naturally knew better and this had generated ill feeling in the village, much of it directed by the Harijans against Basant Singh but perhaps more against the 13-member committee which they described as being composed only of drunkards, opium addicts and other fools who were acting as front men for the rich farmers. This 13-member committee is to play a major role in our story.

Still, in April of 1970, when our story began, much of the jajmani system survived in Ghungrali. The mistry, whose caste occupation in the village was to repair tools, still received 50 kilos of wheat, 50 kilos of maize and 5 kilos of sugar (gur) from every Jat family in Ghungrali and the Nai or village barber, who not only shaved and cut hair but acted as a host at weddings and social occasions and washed up the utensils afterward, received 20 kilos of grain per family every six months. The Mazhbis or sweepers, who gathered droppings in the barns, make cow-dung cakes, removed dead males or donkeys and sang and danced at weddings, still received grain according to a Jat’s number of cattle: 10 kilos of wheat or maize for each buffalo, 5 kilos for each bullock, 2.8 kilos for large calves, 5 kilos for one-year-old calves. The Mazhbis cleaned up after small calves for free until they were weaned.

For these castes, the jajmani system was still very much .operative for the obvious reason that it was profitable for the Jats that it be so.

Not so with the Chamars, whose traditional occupation of leather-working had largely been antiquated by the internal combustion engine and other advances. About half of the Chamars in Ghungrali now lived by raising buffalo and goats to sell their milk at a government dairy or by raising poultry. The most successful of such enterprises was a poultry farm started in 1962 by Gurdial Singh, whom we have already met, who by 1970 had 1,000 birds, including 500 pullets, 400 White Leghorns, 450 Rhode Island Reds and 500 chicks supplied by the United Nations. To avoid adulteration he made their feed himself: rice pulse 40 per cent; groundnut cake, 22 per cent; maize, 22 per cent; sweet pulses, 3.5 per cent; fish meal, 6 per cent; bone meal, 1.5 per cent, stone and marble powder, 3 per cent plus vitamins and minerals. It was a very modern operation; Gurdial sold his eggs to a government poultry farm society in a nearby town on the Grand Trunk Road, which charged a 2.5 per cent commission for shipping and marketing the eggs in New Delhi, nearly 200 miles to the south. Starting with an investment of 1,200 rupees and 100 birds in 1962, he now made a net profit of 5,000 rupees a year and had an investment worth 22,000 rupees. Recently he had taken out a 10,000 loan to build a second story to his poultry building in the village, the Jats being unwilling to sell him land for the purpose, although Surgit Singh, the former sarpanch, and his brother, Sudagar, had stood Gurdial’s, security. This economic success, plus a certain sophistication and a knowledge of the English language, made Gurdial the natural leader of the Chamars of the village and there were some who said he even had ambitions to become the surpanch or elected chief of the village itself. Thus like Basant Singh and One-Eye, Gurdial had a certain vested interest in a polarization of the village into Jats and Harijans since in any election the 160 Harijan families clearly had to vote over the 91 Jat families.

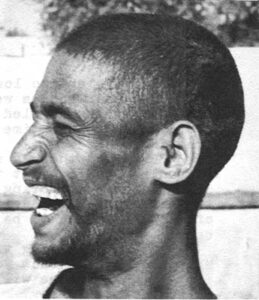

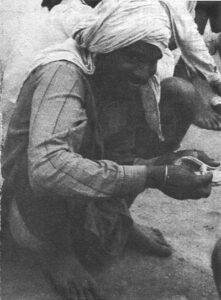

The other half of the Chamars made their living working as either sharecroppers or daily laborers for the Jats and it would not be inaccurate to say that these men, who included Mukhtar and Gurmel, were the real farmers of Ghungrali since it was they who did most of the actual farm work. As a sharecropper, Gurmel received one/eighth of Sarvan Singh’s crop, plus two chapattis and tea each morning. Other sharecroppers worked on a strictly cash basis for around 1,500 to 1,700 rupees a year which Gurmel reckoned after a year of the other was the more profitable. Mukhtar, who did not want to be tied down to working for one Jat family an entire year, received-four rupees a day plus lunch and tea in the afternoon, and although only twenty-three, had worked for 52 of the 65 Jat families of the village.

Traditionally, Chamars who worked as agricultural laborers the year round in Ghungrali had received one-twentieth of the produce. In recent years, until the introduction of the new seeds five years before, Chamars who worked during the harvest at reaping and threshing, received the 20th bale of wheat harvested. With the new high-yielding varieties, the Jats no longer were willing to give the 20th bale and since no new rate had been arrived at, in either Ghungrali or the surrounding villages, this would prove to be the touchstone of the straggle between the Jats and Harijans since a man who got the 20thbale of wheat during the harvest was sure of being able to feed his family the whole year round.

Hence, the introduction of the new high-yielding wheat in Ghungrali in 1965 had been a very mixed blessing since it had set the stage for a social and economic confrontation between the Jats and Chamars that would upset patterns of living established over long centuries.

In April of 1970, it would hardly seem to matter that the Jats were asserting their claim of ownership to the land. The Harijans’ right to go into the Jats’ fields to gather fodder for their cattle had gone on for centuries and it was assumed by the Harijans that it would go on for centuries more. Not so in May 1970, as we shall see.

It was Basant Singh and the modern, rich farmers like him who thought in twentieth century terms of economy of operations and returns, not most of the inhabitants of Ghungrali many of whom remained ignorant of the world beyond the village, had never heard of Vietnam, much less that there was a war there and even did not know that human beings had actually landed on the moon.

Nor did they much care what went, on outside the village. To them Ghungrali was not only a place but a universe. It could be seen, its eighty-seven allotments marked out in boundaries, pinned down on a map. Here was the banyan tree, there the Gurdwara, the mill, the school, the many houses of brick or mud, huddled together with their backs to the lanes. The wheat fields were round about, located in terms of canal, wells, roads or trees. All these could be perceived, they had a feel, smell and sound to them. But the village was much more; its huddle of houses was a community.

It was not divided into mere economic units like Basant Singh’s figures, but men, women and children who thought in terms of relationships, of factions, of ties, of family, of kinship, of many rights and obligations. This feeling extended outward also to the other Sikh villages of Punjab. Half of the adult members of the village, its women, moved away and were replaced by girls from nearly 400 surrounding villages. Between these other villages and within Ghungrali itself there were duties, privileges, connections, links, each with their special flavor and unique value, a meaning in terms of the life of the whole.

Each of the three main groups of Ghungrali’s inhabitants – the Jats, the Chamars and the Mazhbis – was divided into factions based on place of origin and kinship. These kinship groups provided a sense of identity even more intimate than the village or caste membership and performed important social, economic and ceremonial functions as well as provided platforms for struggles against each other or for power in the village.

For most of the time since 1947 until 1965, Ghungrali had been dominated by Basant Singh’s Jat faction, which controlled the power structure through majority membership on the village panchayat, the Cooperative Society and the Gurdwara committee. But in the last election, in 1965, the Harijans had turned against Basant Singh for ill treatment of his laborers and instead elected one Pritam Singh – no relation to old Pritam – an easy-going young man who if he drank too much was very tolerant toward the Harijans and was also Charan’s best friend.

Basant Singh’s faction included Surjit Singh, the wise former Sarpanch, and most of Ghungrali’s richest, more conservative and more cultivated families. In contrast, the faction led by the new Sarpanch, Pritam Singh, which included Charan’s father, Sadhu Singh, his uncle Sarvan and cousin Dhakel, was composed of more tolerant, poorer and less educated Jats, including a circle of recently well-off and comparatively young men who spent a great deal of their time drinking, carousing and fighting with one another. This circle tended to gravitate around Charan and most evenings could be heard laughing and joking over a bottle at his cattle yard. The Sarpanch had beaten Basant Singh’s candidate, Surjit Singh, by a majority of 400 votes out of a total of 1,200 cast. The other two Jat factions in the village were of little importance, one of them loosely composed of those who could claim no ancestral village in the nearby region such as One-Eye, who had been a taxi driver in Delhi.

There were four factions among the Chamars, the two most important being led by Gurdial, the poultry farmer, and Mukhtar, who although, only 23 had completed nine years of schooling and was considered one of the most educated and responsible of the Chamar young men. Among the Mazhbis there were only two factions. The first, led by a highly respected old man named Charan, who often helped Charan during the busy seasons, was highly traditional; some of its members served as part-time Sikh priests and Charan himself was a staunch traditionalist who opposed any erosion of the cast system with its mutual rights and duties, whether within the village itself or imposed India’s liberal post-independence government which sought-to outlaw untouchability. The other Mazhbi faction was led by old Bhoondi, whose sons opposed the caste system and wanted to end it. (During my stay in Ghungrali a historical precedent was made when Sher, Bhoondi’s oldest son, invited myself, my interpreter, a high-caste Jat, and Mukhtar to dinner one evening. It was the first time in Ghungrali, that either a Jat or Chamar had eaten together at the home of a Mazhbi and it provoked criticism from the elders of all three castes.)

Factionalism, however, was not as strong in Ghungrali as in some of the surrounding villages. In the neighboring village of Govindpura, a fortress had been erected in the center of a 100-acre holding seized by force by the survivors of a Jat named Karnail Singh. The land had originally been given to a Hindu Sadhu by the surrounding villagers to build an abbey. After his death, Karnail claimed to have been the Sadhu’s chela or disciple and that the Sadhu had willed him the land. But a second will was found in which the Sadhu left the land to another Jat Sikh, around whom formed a party known as the Birkishan. A nearby landlord named Chanan Singh went to court to try and get the Sadhu’s land away from Karnail Singh but was murdered. This led to a series of at least a dozen murders between the two rival factions, including Karnail Singh’s own death. By April of 1970, both factions had started rival trucking anions in the nearby Grand Trunk Road market town of Govindpura and were centered in armed camps at Govindpura, a mile to the northeast of Ghungrali and Nawapind, another village a mile due east. One of the factions was linked with a group called the Libra party which was involved in Punjab state politics and both factions were armed with jeeps, rifles and gunmen, which sometimes rumbled through Ghungrali on the way back and forth to the Grand Trunk Road. The villagers of Ghungrali had little to do with either faction, although some, like Charan, were on friendly speaking terms with both sides. The fortress, erected by Karnail’s family, was almost medieval in appearance with towers and gunslots at which ladders were palled up at night to avoid surprise attacks.

In Ghungrali, membership in factions was important; but as we shall see it was not binding. Indeed, Basant Singh and has friends claimed the only thing that divided the village was drink.

“In our faction,” Basant Singh would say, “we don’t think of anybody as our enemy. Since the Sarpanch and his cronies are on the wrong path, they think of as us opponents. Such attitudes can develop into fighting. Surjit Singh was the sarpanch of this village for eleven years and did an excellent job. We have no drinking type of person with us, that’s why there are two factions. Surjit has never touched drink or meat in his life. That’s the touchstone, drink.”

“This drinking is enough make a decent person ran to the towns.” Surjit Singh would agree. “This village could be a fine place to live if you had some guarantee under the law that your life and property are safe. Then these factions. A nice person won’t get any help from the other Jats if his sharecropper runs away or he gets into some other trouble with the Harijans.”

“Now we have challenged them,” Basant Singh would go on. “I carry a rifle sometimes. Why? Because we have told them, after drinking you can’t enter our area. We’ll just teach them a lesson if they dare show up around here drunk and disorderly. They have no other business except drinking, those young men around Charan. Oh, Charan himself is not bad but they have a bad influence on him, Charan can’t hide anywhere. They’ll find him, them and their bottles, and he can’t escape.”

“They will be in deep trouble a few years from now,” would nod Surjit Singh. “That son is very fond of drinking.”

“If anybody drinks and stays sober, I don’t mind,” Basant Singh would reply to Surgit Singh, who suspected his friend of secretly taking a drop at his well now and then. “But the Sarpanch, and Charan and their friends create trouble, shouting and laughing and carrying on. We can’t say if we call the police whether they’ll help as or not. It depends on whom runs to them the fastest and gets there first with the money. There is no law and order in Ghungrali. None. Absolutely none.”

The Hunt

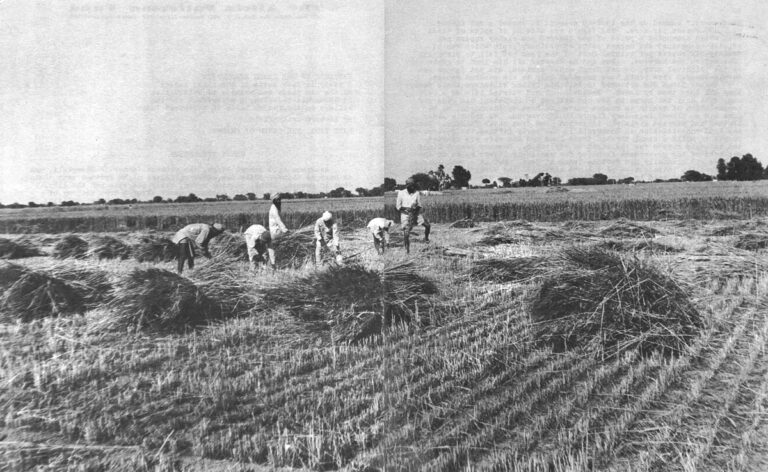

The wheat was ripening now, the sky grew paler each day and the clouds that hung in high puffs for so long in February and March were dissipated. The sun flared down on the ripening wheat day after day. As the sky became pale, the earth became pale, a burnt gold in the once-green wheat fields and white in the fallow land where cane had been planted. Then it neared mid-April; on the 13th, Baisaki, the harvest traditionally began although everything seemed late in ripening this year. But as the son shone more fiercely each day, the golden lines on the wheat leaves widen and moved in on the central ribs and the heads of grain paled into yellow. The air was thin and the sky more pale and every day the green earth paled into a faint gold. In the roads where the bullock carts moved, where the iron wheels milled the ground and the hooves of the bullocks beat the ground, the dirt crust broke and the dust formed. Every moving thing lifted the dust into the air. And by the 10thof April, the dust came in so thinly that it could not be seen in the air and it settled like pollen on the tractors and bullock carts, on the trucks and cars on the Grand Trunk Road. The people brushed it from their shoulders and Charan began to have more serious asthma attacks in the night.

Five days before the harvest traditionally began, the Jats of the village gathered at the Gurdwara and called a meeting of the thirteen-member committee which had settled the matter of the four rupee daily wage with the Harijans the previous August. The Jats told the committee to fix the terms of labor during the coming harvest and that they would abide by its decision. This was first opposed by the Sarpanch on the grounds that each Jat and the Harijans he hired should decide their own rate of payment. But after Basant Singh and Surjit Singh spoke he was overridden. They argued persuasively that the previous two years, when they had given the harvest laborers fifty to eighty kilograms of grain per acre they had suffered a financial loss. Nor did they wish to return to the traditional jajmani system of paying each worked the 20th bale reaped since, they argued, the new high yielding varieties of wheat were at least four times richer.

Finally the committee, led by a fiery-eyed retired army sergeant, Tara Singh, and including among its members Charan’s uncle Sarvan, his friend and drinking companion, Nirmal, and Mohinder, the one-eyed one, decided to pay the Harijans the 30th bale; they said it would be a general rate applicable on all sixty-five farms of the village, whether the crop was good or poor. For three days the Jats broadcast their, decision from the village loudspeaker and there was anger and dismay in the Harijan quarter since the 30thbale was too little on all but the richest wheat fields of the village. After three days, they sent a spokesman to the Jats who told them, “We Harijans are not agreed to reap your crops on the 30th part. We will take only grain as we did the past two years.”

Then Tara Singh answered for the committee, “Grains, we won’t give. We can talk about some arrangement in terms of bales, but our position is we want you to accept the 30thbale.”

At this the Harijan spokesman, one Teja Singh, became angry. “Do what you like,” he said. “We won’t come and we’ll see how you cut your harvest.” Then the committee reported back to the Jats of the village, “The Harijans have insulted as; they’re not willing to talk to us.”

And so, as the wheat ripened in the fields, there was ill will and talk of approaching trouble in the village. But the sun lay on the fields and warmed them and in the shade under the grass, the insects moved, ants plodding restlessly on many feet. Water flowed from the tubewells, free and clean, into the canals and each watering day Mukhtar would go with his hoe, opening and shutting the gateways of earth and gradually irrigating the many acres of land. And when the water moved deeper on part of a field and around the stems of the ripening wheat, he would skim off the surface dirt between the stalks and throw it into the water until the earth was watered evenly. And the days got hotter and hotter.

And now, this evening, at last, when the sun was about to descend towards the west, the plain, the trees, the air could no longer bear the pressure; their patience worn out, they made an attempt to throw off the restraint. Beyond the white distance, unexpectedly appeared an ash-gray curly cloud. It exchanged a glance with the plain and looked threatening. Immediately there was a rift in the stagnant air, the wind sprang up and with a clamor and a whistling whirled through the ripe wheat fields.

At his well, Charan took advantage of the sudden wind to burn off the chaff on his sugar cane field. He lit a pile of husks and ran along the edge of the field leaving a red line of flame. The fire moved quickly in the wind across the field, from northwest to southeast and insects must have rushed to the southeast corner because crows began frantically dashing around it, flapping their wings and bobbing their beaks up and down from the ground. “Life feeding on life,” Mukhtar told Charan and then they both looked up in wonder as a great black bird with blue-tipped wings soared overhead, the Garar or most sacred bird of Hindu mythology.

Just then the Sarpanch passed on the road, carrying a shotgun and followed by Mohinder, the one-eyed, who carried two dead partridges by the neck.

“Go straight to that white pumphouse over there,” Charan called, “there are peacocks in abundance.”

“Yes,” Dhakel called as they passed his well, “There was one here in the morning. I was here, right here.”

“It was here. I saw it yesterday.” called Pritam, who was bent down cutting fodder.

As they followed the paths on the bonds across the ripe wheat, the Sarpanch said little, intent upon the hunt, but One-Eye spoke almost continuously. “Basant Singh agrees the Harijans are in the wrong. They are exaggerating things. I have heard the Harijans are going to the police. How can they go to the police when there is no fighting?” He spoke in a high, obsequious little voice, which rose to a whine and then dropped to a confidential whisper when he introduced a new name into his remarks. “They wrote to Mrs. Gandhi. They can write to anybody they like. How can the police or Mrs. Gandhi tell the Jats how to ran their farms? Those Harijans have two or three buffaloes and are going further and further from farm labor. They meekly go and cut some wheat or oats and hide it under their weeds and grass. We went to Arjun Singh’s field and saw where somebody had taken wheat from his land.”

Charan called behind them, “Go straight to that white little house. The birds are near that well.”

“The people there will mind it,” hissed One-Eye.

“I have killed hundreds there,” mattered the Sarpanch. “They don’t say anything. Just ‘Sat Sri Akal.’ Come with me. I’ll show you were it is.”

“The Harijans have progressed faster than the Jats,” One-Eye went on. “That’s why they complain that they get less. Now these Harijans have a taste of prosperity.”

“The partridge is a very clever bird,” said the Sarpanch, who was not listening.

“Is this field Mamaji’s? His wheat is a record. If you throw dust on it, it won’t touch the roots of the plants. They take a lot of money out of this field every year. I have relatives….”

The Sarpanch interrupted him. “Listen. There are partridges here. They are playing that way. Just that side. They keep sitting in the wheat field.”

“We will not allow the Harijans in oar fields if they don’t cut. the wheat crop. They thought we would come running, ‘O, Harijans, we’ll help you. We’ll sacrifice.’ Now we are quiet. We’re waiting to see their next move. They’ve spent fifty rupees.” He giggled in a high squeaky voice. “Hi, hi, let them spend some more and we’ll get a settlement!”

The Sarpanch muttered, “This gun’s range is not that far.”

A passing farmer called, “What’s that? Are they partridges?”

“Yes, yes,” One-Eye shouted back. “When you cut the crops they ran away.”

“We’ll have a lot of pigeons,” the Sarpanch said. “They must be within this field.

“O, my friend.” said One-Eye, “when I was in Calcutta one would have a single shotgun and held be a big landlord. I used to think they were very rich with money but they were nothing. They only wore a white dhoti.”

The Sarpanch, motioning One-Eye to stay back, went to the corner of the next whet field, and laying across a band, raised his gun. The grain at once began to shisper, a spiral cloud of dust got up from the road, and fled over the fields, drawing after it bits of straw, flies and feathers, and the darkening, twisting column rose toward the sky. The wheat flattered and tossed and one patch got caught in the whirlwind. The grain twisted, bent and swished in all directions and then lay flat and broken on the ground.

“‘Whose wheat is this, Brother?” One-Eye called. “That patch is ruined. Almost ruined.” A hawk took wing from the side of the road; it flashed its wings and tail in the son’s glare and resembled a giant fish. with its shimmer of speckled colors, then probably frightened by the cloud of dust, it shifted to one side with a flash of its wing.

Next, alarmed by the whirlwind and not understanding what was the matter, a flock of white herons rose from a newly-watered field of grass. They flew into the wind, looking angry and important. Only the crows who had grown up on the Punjab plain and were used to its disturbances, calmly flew from tree to tree or perched in the grass, placidly, without heeding anything, prodding the hard ground with their beaks.

“If we get a peacock it will serve our purposes.” called One-Eye. “Then we can feed a whole family.”

The Sarpanch stood up, the birds had gotten away in the whirlwind. “There were two. I wanted them to come into line. Shall I shoot pigeons?”

“Yes, go ahead. They’re very clever.”

The Sarpanch fired and from a distant electric line a pigeon flattered to the ground. The two men advanced to pick it up.

“Now they understand,” One-Eye grinned. “Everyone wants his life. There were so many around here when you fired.”

“They stay in that well.”

“You should have fired into the well itself. There are more on the wire now. They’re in line. Why don’t you shoot and make them fly?”

“We don’t have much ammunition with us.”

“That’s not a peacock. It’s a man cutting sugar cane.”

“When you don’t need peacocks, they are always around you,” said One-Eye, “I’ve seen many partridges here. O, there’s a dove. One Harijan lives just a neighbor to the Hindu’s shop. I go there and get every information.

“You find so many partridges in open places these days,” said the Sarpanch. “O, last night I was full of liquor up to here. This is the right season for partridge. Docks don’t come here; there is no water and it is not lonely enough. The best time is early in the morning or evening such as now when the sun is coming through the grain. But tonight there is too much wind. Most of the partridges will be killed when the crops are cut. The children and dogs will get them. The dogs chase the partridges until they are tired and then the children kill them with sticks and stones. Let’s go back. It’s too windy.”‘

As they turned back the sound of distant thunder followed by a little breath of fresh air came from the north.

“If it goes on like this until dark, it may rain,” the Sarpanch said.

“Before last year in the summer the Harijans exploited as because we were not united, we Jats,” called One-Eye, falling behind as they walked along a furrow. “There were political Jats, they were palling our legs. But we have shunted them out, those vote-seekers,, and replaced then with people who don’t worry all the time about getting the votes of the Harijans.”

The Sarpanch frowned, thinking this a reference to him. “Now the poor people, those Harijans who have no work except daily wages, will suffer. And it is always evil to make the poor people suffer. It is those Harijans with dairy or poultry operations, they are making this fuss.”

“Yes,” hissed One-Eye. “It is Gurdial Singh who is seeking to replace you as sarpanch. Ah, that is his game. He is very close to the police I have heard. One day Gurdial, he looks like an opium addict, a police official started beating him and demanding to see opium on him. From that day on he must send a dozen eggs a day to that policeman’s house. So I have heard. Basant Singh said…”

The Sarpanch cut him off. “We can’t say anything. We’ll call the Harijans and we’ll discuss everything. It will all be settled in a day or two.”

One-Eye, rebuffed, was silent for a time. Although with his glass eye he looked presentable, today as he often did, he did not wear it end his left eye was only an empty socket like a dark cave you were afraid to look into for fear of what you might see.

Now little by little an invisible power fettered the wind and the air, laid the dust, and once more, as if nothing had happened, silence returned to the plain. The cloud passed south and disappeared over the faint outline of Bhambadi village, the sun-burned fields grew crisp and dry, the air stagnated; only some startled sparrows twittered and dashed among the treetops, complaining of their fate. Soon after the two men joined Charan at the well for an evening’s drink, daylight crept away.

The Storm

The air was heavy the next morning. The rising sun looked faint and wan, the sky white and gloomy, the mist very dense and the distance hazy. All the Punjab plain seemed apprehensive and languid and even early in the morning there were some faint, distant flashes of lightning.

Everyone was oat of sorts. Charan awoke with a headache from drinking too much at the well the night before. Daring the evening the Sarpanch and One-Eye had offered him the job of being depot holder for the Cooperative Society’s fertilizer.

“You can keep it in your barn,” One-Eye had said. “The secretary, myself, and the depot holder should cooperate with each other. We’ll give you forty rupees for a godown and ninety rupees as monthly salary for your services.” Then One-Eye’s voice had lowered to a whisper. “You can save money by taking bribes. There is one technical point a salesman can exploit, Daimonium; you can save it and just give them sofer and urea. If you don’t put dai then when you reap your wheat, your yield will be about 20 per cent less. If you don’t put dai on your fields. When Basant Singh was president of the Cooperative Society, he never gave dai. If you saw those crops of persons who didn’t get dai, you’d see the difference and there would be blood in your eye.”

Charan had accepted but now in the morning he had his doubts. Amar Singh the present holder, was old Pritam’s brother and a friend. He should have consulted him. Also he did not want to be involved with One-Eye. He suspected the Sarpanch had only made him, general secretary of the Cooperative Society because Mohinder had something on him.

As they drank they had cleaned the birds and Mohinder had pressed the Sarpanch to register some land for him. “You must have legal proof,” the Sarpanch told him. “Ah, yes, I will have, “One-Eye had replied. “I’ll bribe the land officer. Sometimes my elder brother would refuse to give some twenty or thirty rupees to the land officer. He spoiled our game every time. Some court cases were in my family and I have experience.”

“He is an evil soul,” Charan told himself, rising from the cot in the cattle yard where he had spent the night. Heavy with sleeplessness, untidy, unattractive, he went over to the pump, and splashed cold water on his face. His father, Sadhu Singh, who had also started sleeping in the open cattle yard during the hot weather, rose and complained loudly for his morning tea. Charan sent Peloo to the house to fetch it.

Mukhtar and Sher entered the cattle yard and Charan brightened up on seeing his two Harijan laborers. “O,” he laughed, watching for any signs of ill will because of the harvest trouble, “I drank too much last night.”

Sher laughed. “Charan can move lightly even after a fall bottle of ram. He’s not affected by two bottles even.”

“Gurmel is back today,” Mukhtar said. “He went to a marriage party. He said it was very good. He did not go along with the party to the bride’s village but stayed behind at the groom’s house and drank. There were girls and women dancing and singing songs.”

Charan laughed. “Some of these young girls, like those at the mela, they whistle at the boys to meet them at such and such a place. The homey type of woman comes early in the morning to a mela, says her prayers and goes home. Those who want to be pinched on their bottoms stay until afternoon.”

The youths laughed. “So. come young men, we must haul manure today and the weather looks bad. I’ve backed the lorry up outside so you can start loading and I’ll come and drive the tractor.”

As the two Harijans went out the gate, Charan’s wife entered carrying Sadhu Singh’s morning tea. The old man groaned, sat up with some fuss and effort and poured two glasses, for Charan and himself. Outside in the lane there was the sound of drums and bagpipes, the Mazhbis playing for a departing wedding party. Charan’s wife went inside the barn to unhook the shutters from one of the barred windows and see outside.

“It’s a wedding party,” she called in her soft voice. “They re the village watermen. They’re the rajas. 0, there stands one of the rajas in white clothes. How clean he looks today and how happy he appears.”

Charan joined her at the window. “O, look, they are just leaving now.”

“They are taking a band also,” said his wife. “O, how the children are scrambling for the coins.” Then, as if she had forgotten herself in front of her father-in-law, Charan’s wife held her scarf up to her face and hurried from the barn, getting a scolding from the Old Lady who was just entering the gate and who was the chief cross she had to bear as Charan Is wife.

The Old Lady at once screeched to her husband and son in a load angry voice, “There’s not a drop of milk in the house! Now, you two are sitting here like kings and ordering tea all day five times each!” The Old Lady, her pendant stomach protruding under the lose shirt and pajamas she always wore, went to the buffaloes and started to milk, screeching at them all the time.

“You could have arranged for more,” grumpily called Sadhu Singh without looking at her. “Ask the milk sellers from the dairy. They’ll give you milk.”

“Three times I sent tea to Charan at the well yesterday and five times to you here at the barn. What is this man doing sitting in the barn all day and inviting people to tea? Does he drag them in from the street?”

“Three times I sent tea to Charan at the well yesterday and five times to you here at the barn. What is this man doing sitting in the barn all day and inviting people to tea? Does he drag them in from the street?”

“It Is none of our business,” said Charan, coming to his father’s defense. “Women know what’s what about the food. Why don’t you order two kilos every day from the dairy? You know we’re short of milk.”

“I will order ten times a day” declared Sadhu Singh grandly, annoyed to be the target of his wife’s bad temper so early in the morning. “It’s none of my headache to look into the milk bucket. What are you here for? Do you think our buffaloes are dead?” He harrumphed with indignation, sarcastically mimicking his Wife, “The child couldn’t get a drop of milk.”

Charan said, “Why don’t you stop now, mother. You are making a scene. Go and milk your buffalo and arrange from tomorrow two extra kilos a day. That’s all.”

Sadhu Singh, fully annoyed and agitated now, seemed to huff and puff with irritation.

Charan called to the mote stable boy, who had stood watching the family quarrel with some interest, “O, Peloo, go to the house and get your breakfast and come back at once and then we’ll go.”

“‘Why this dirty pig should eat first?” Sadhu Singh exploded, seizing upon Peloo to vent his spleen on. “He was roaming about all day yesterday! Come, come, come, Charan, let’s go and eat now. I know what you want. You have a bottle hidden somewhere. There should be an end to that thing!”

Charan, taken aback by this outburst, shouted with some heat at Peloo, “Go, go run and come back soon, Peloo!”

“Come,” Sadhu pressed on. “We’ll send one of the children back to watch the barn in our absence. Why are you dragging your legs? Come.”

Sadhu Singh rose and marched to the gate but Charan, angry now, remained sitting. “Let him eat first,” he shouted at his father. “He’s hungry. He’s been up with the cattle since four, the poor crippled man.”

“Have the calves milked him?” Sadhu Singh shouted back from the gate. “What’s he hungry for? He was roaming about from this street to that street yesterday and he’s a cripple man you say. This dirty Chamar, he’s a dog!”

Charan was to angry to speak. His father stomped down the lane, cursing and muttering under his breath, “I know what Charan wants. He has a bottle hidden somewhere, the dirty dog. I rape his mother. He’s like a dog, wagging his tail after anyone who has a few drops of liquor. The dirty dog. I know what he wants. He’ll go into the streets and beg one day if he doesn’t mend his ways.”

No sooner had Sadhu Singh marched off, than Mohinder, wearing his glass-eye, entered and sprawled out on the father’s bed with its rumpled quilt.

With a proprietorial air, One-Eye surveyed the cattle yard and asked, “Where are you going to stock your fertilizer?”

“I’ll dump it at the well house,” Charan said wearily.

“That’s expensive stuff. Don’t take risks,” said One-Eye. “Somebody may come to take.” As they spoke, old Bhoondi, his wife and two daughters came to clean the barn and as the women worked, Bhoondi sat on the ground near Charan’s cot, listening to him and One-Eye and lighting up a cheap cigarette.

“Moreover, officials come to check the stock,” One-Eye admonished him. “You can’t take it to the fields. They’ll want it here.”

“I’ll want six thousand bricks and I’ll build a small house in that corner of the yard,” snapped Charan.

Seeing the other in a sour mood, One-Eye took his leave, saying, “All right, Charan, but it will be an enormous stock.”

An old neighbor lady with fat pink cheeks entered the gate. “Look,” she called to the Old Lady who was still milking, “Here is Bhoondi sitting with his legs crossed. He’s enjoying life.”

“O, I have worked enough for my life.” said Bhoondi. “I have four grown sons and don’t have to work any more now. How can a person go on working ’til he dies.” Bhoondi had been cleaning the good housewife’s barn for more than twenty years and the two of them chuckled and cracked jokes until the Old Lady screeched at Bhoondi in her load angry voice, “Bhoondi, your grandchild came here and he destroyed our chili plant.”

“No, no,” Bhoondi replied. “There are so many children around. It could be any. Not my grandchild. We’ve never brought him here. You are telling the same thing Sadhu Singh was telling. How could you have such an idea? If some child has spoiled your chili plant, dear lady, it won’t bring your house down to earth.” Bhoondi giggled, in has deep rich voice.

“O, that I know,” called the Old Lady from her milking stool. “But you know children are very naughty. We have some vegetables and pumpkin plants here. They may spoil them tomorrow.”

“Give me a basket of that green fodder you have,” called Bhoondi. “I need it for my buffalo.”

This brought a shriek of indignation from the Old Lady. “You want that somebody should bring a dish of prepared food and put it in your mouth so you can eat! You don’t want to cook yourself! Why don’t you go to the fields and cut some fodder yourself?”

Bhoondi chuckled. The Old Lady was really a terror. “‘Why can’t you tolerate such a small thing?” he asked, needling her. “By evening this fodder will get dry. If a poor man’s buffalo eats this fodder, it won’t ruin your heaIth.”

“Yes, yes, it makes no difference to us but how does it make any difference to you not to go to the fields yourself and cut.” She rose and, carrying her pail fall of milk, advanced on Bhoondi threateningly. “You are just sitting here and gossiping and moving all day around the barns.” Her voice rose to a piercing squawk. “Move your limbs and get some from the field, you gossipmonger.”

“Now you come with me,” Bhoondi’s wife called. “Let’s go clean the other barn.”

Bhoondi remained sitting comfortably and thundered at his wife in his deep voice, “Don’t make such a noise standing over there! Get along with your work! I’ll reach myself. I have legs. This gentleman is talking to me and you are just screaming over there.” His wife and the Old Lady both hurried to the gate and Bhoondi chuckled to Charan, “These women, they need to be sent to an asylum. They scream too much around here. But they’d teach them some good things, heh, heh, heh.”

Outside by the manure pile, Gurmel had stopped by on his way to the fields to speak with Sher and Mukhtar. “I heard the police are furious with the Jats,” he told them confidentially. “They say the 30th bale is unreasonable and that the Jats are just trying to use their force. Today some of the Harijans are going to the police at Khanna. One appeal has been sent to the Deputy District Superintendent in Ludhiana and another to Indira Gandhi. The Harijans are thinking of forming a committee. Would you join it, Mukhtar?”

“Yes. What about Sher?”

“So far the Mazhbis aren’t involved. It’s the Chamars only. And only those who are daily laborers; not the sharecroppers like me.”

“I heard the Jats were so mad at Teja Singh they’ve threatened to ban him from their fields for a whole year,” Mukhtar said.

“What will you do if trouble comes?” asked Sher.

“I don’t know. Sindar’s a fool but I’m happy working with Dhakel Singh. He doesn’t ask me to do more work. He’s soft spoken. He doesn’t bark vulgarity all the time like that Sindar.”

“But Dhakel is a Jat. And the Jats are all alike.”

“Even Charan abuses too much,” Gurmel said. “Like ‘you are not my wife’s brother’ or ‘I’ll rape your sister’ or “I’ll shove a stick up your mother’s.”

“Pritam never abuses anybody. He doesn’t speak vulgarly and he’s always busy with his own task,” said Mukhtar, trying to be fair to the Jats. “But you never know. He may have a dirty record.”

“Once Charan abused Sarvan Singh and Dhakel and then they shoved him to the ground and gave him a good beating,” Gurmel said. “He was almost half dead. It was some years ago. Charan came with a spear to frighten that opium eater and those two and Sindar caught him.”

“Everyone drinks too much in the village,” Sher said. Even the Harijans. Two years ago everyone would drink in the evening, put a spear on his shoulders and walk around the streets yelling, daring anyone to stop him.”

“Sintok’s father was Charan’s matchmaker and once Sintok was quarrelling with three villagers. Charan went there to support him and they caught both he and Sintok and gave them a good beating. One man tried to hit Charan with a sword but it stuck in its scabbard or he might have been cut to pieces.” Gurmel paused. “Basant Singh drinks secretly. We drank so many times with him at his well. He has the contract for selling liquor in Ghungrali for nine years now.”

“I used to drink heavily but I haven’t had a drink for at least one month,” said Sher.

“I hear the Sarpanch is against the thirteen-member committee. He doesn’t want the Jats to try and force a general settlement on us.”

“Yes,” said Mukhtar. “Pritam Singh is a good man. If someone’s ill, he’ll take him to the hospital. He and Charan are fast friends.”

“It looks like trouble in the village now,” Gurmel said.

“We’ll tell the Jats we’ll take the 30th bale but only on the best crops otherwise it will have to be adjusted. Wheat prices have gone up tenfold in the last five years, which is the real trouble. The new varieties need only four times as much water and fertilizer. The Jats are getting more prosperous and don’t want to share it. All the Jats are united and all the Harijans are united. If there’s no settlement, we may have to stop working for Charan.”

“He’s coming now,” Sher said. “Will you tell him?”

“Keep quiet, don’t speak,” Mukhtar said in a low voice as Charan approached, laughing and calling, “Let’s go to the fields, young men!”

Before lunch they were able to haul two loads of manure to the sugar cane field Charan had freshly burned. The horizon grew slowly blacker and by eleven o’clock a pale light was already blinking on the northern horizon and the blackness, just as if it had weight, was beginning to bend to the right. It looked like a thunderstorm was gathering, and as each one glanced at the darkening northern sky from their work, they thought: May God grant as time to gather in the wheat harvest. Then they remembered the harvesting terms still had to be settled and between the sky and the uncertainty, they were cheerful and happy, but a little uneasy.

Charan, sensing the workers were troubled, was more animated and cheerful than usual. He joked as he helped them lift the baskets of manure on their heads to carry to the trolley and on the road to his fields, shouted to everybody. “Now you work hard and earn your body,” he called to a vacationing sub-inspector working in his father’s fields. “Otherwise you’ll be all flabby!” “Don’t fall off,” he called to a passing boy on a bicycle, who shouted back, “Don’t worry, Charan. I wasn’t born on that day.”

And always he kept laughing and working, seemingly in the best of spirits.

All the while he kept talking, “O, see that padihqui bird! You know it sleeps on its back with its feet in the air. They say that if it doesn’t sleep that way the heavens will fall.” Or as they spread the manure he would call from the tractor, “O, just small heaps, young men. Two baskets each. Just try it. Shabash, shaba-a-a-ash, that’s how to do it. Is it hard from there, Mukhtar? My, boys, get it a little farther. We’ll only take two trolleys this morning. One should last for two and a half rows. Just cut the corner a little more. Bas! Come now, come now, young men, show your strength!”

And Mukhtar would joke, “Charan made an excuse to take the trolley back after the mela but he really wanted to enjoy his sister-in-laws.” “Don’t impose new laws on, daily wage laborers, Sardarji,” Sher would call or “Basant Singh has a, really good trolley; they spent four thousand rupees on it. But yours is all right.”

Or Charan would chatter on aimlessly. “There are three or four Surjits in this village. One is called the horsewallah. He brought a horse and tonga from Pakistan. Everyone had them there. When he first came he had nothing to do and worked as a tonga driver. When he first got his land allotted here he used horses for plowing. People thought it strange and joked about it.” Or “One time I went to Madras and kept money in my shirt pocket. People looked at me suspiciously. I asked in a gurdwara that I saw people with only coins and no notes in their hands and pockets. They told me in Madras people keep money on their inside pockets. Here I was on the bus with 1,200 rupees in my shirt and everybody watched me. Stop, hey. Let’s go, boys. I have told my sons that if they don’t get first class in their tenth exams, I’ll send them right back to the farm.” Or “We’ll go and eat. You can earn 100 maunds of wheat if you use your tractor to plough for others. But I’m alone. I don’t have much time for that. If I kept a driver, the machine is lost. He won’t take care of it as I do. I know that after so many days I have to change diesel oil and after twelve hours of working the tractor I must grease the clutch plates. Suppose I drive the tractor twelve hours and forgot to change them and another man drove the tractor for twelve hours after that. The diesel plates would be gone.” And so on throughout the morning