The marginal ten, the wretched stragglers for survival on the fringes of farm and city, may already number half a billion. By 1980 they will surpass a billion, by 1990 two billion. Can we imagine any human order surviving with so gross a mass of misery piling up at its base?

— Robert S. McNamara in a speech to the World Bank’s board of governors, 1970

The last time I saw Paris

Her heart was young and gay

I saw the laughter in her eyes

In every street café…

(Introductory note: This is the fifth and last case study in this series of articles exploring – in the daily lives of ordinary people – the human impact of overpopulation. The previous four studies dealt with the problem’s historical development, the first true Malthusian breakdown, the transfer of farm technology and urbanization. This study concerns emigration and the confrontation between the poor countries and the rich as revealed in a journey from a green valley in the Maghreb into the Arab slums of Casablanca and Paris. A final, eighteenth, report next month will sum up the entire series.)

The Maghreb, the former French region of North Africa comprising Tunisia, Algeria and Morocco, is one of the world areas where the pressure of population is acute producing for many the slide into “misery and vice” Thomas Malthus predicted in 1798 could eventually overtake all the world. There is a decline in living standards, a population growth rate of from 3 to 4 percent, 40 percent unemployment, widespread malnutrition and high rates of alcoholism and drug addiction. Often a passport to Europe seems like an admission into paradise. This is an attempt to portray the reality for one emigrant. Although used selectively, all of the dialogue has been drawn verbatim as it was recorded at the time or reconstructed soon after an event. I wish to express gratitude to the governments of Morocco and France; the American missions in Rabat, Casablanca and Paris and especially to two Moroccan secretaries, Madame Bitou and Mademoiselle Amor. Of special assistance was Steve Josephson, a twenty-two-year-old Peace Corps volunteer from Stillwater, Minnesota, who appears in the, story. And, as always, one is extremely grateful to the ordinary villagers for their kindness and hospitality.

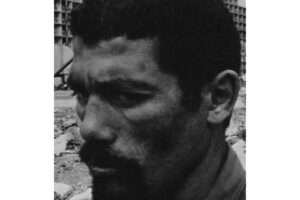

Above all, I am indebted to M’Barek Ben Abdesalem, who was both the principal character and my interpreter for this study and whose intangible opinions and personal memories provided almost as much material as the dialogue itself. Midway in the preparation of this report, I addressed a UNESCO conference and found the audience – contrary to the many reports about growing isolationism in America – extremely interested in the poor nations. After I spoke, a distinguished Negro physician rose to argue persuasively against American involvement abroad, saying, “It is no time to worry about cousins down the street when there is juvenile delinquency in your own house.” I made no rebuttal but thought to myself, “Barek is not your cousin, doctor. He is your brother. And mine.”

The Principal Characters

BAREK

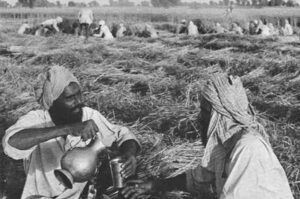

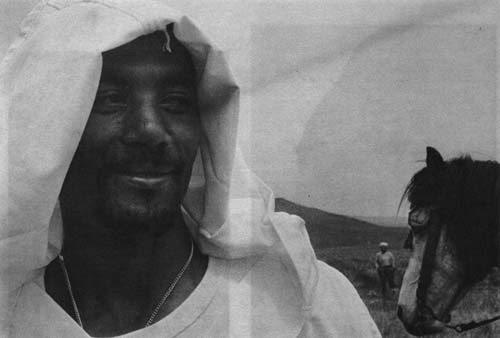

Barek, STEVE and HADJ in the green volley

Mohamed’s wife, mother and MUSA

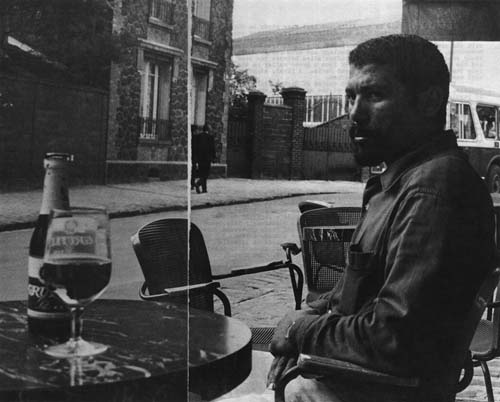

Barek and PIERROT in Paris

The Marginal Men

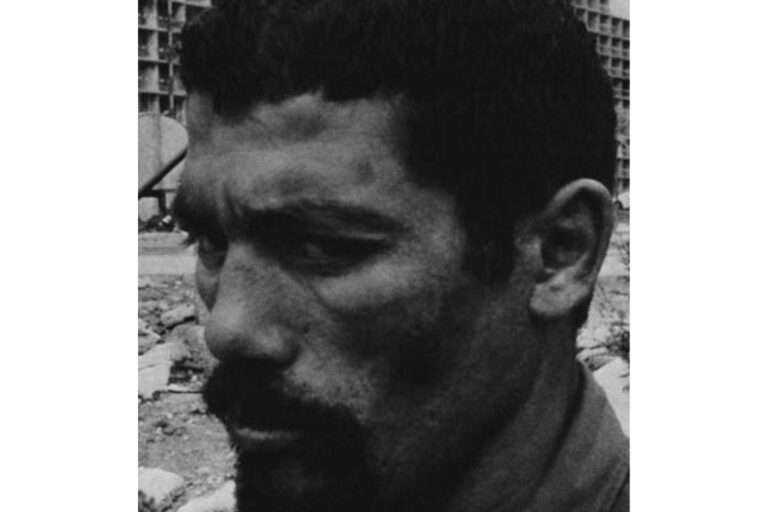

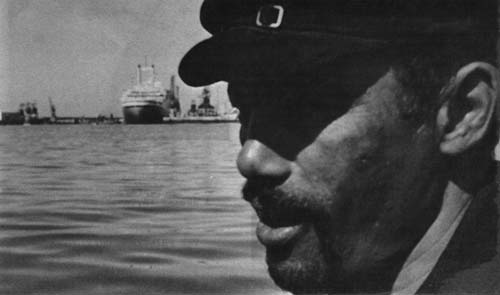

M’Barek Ben Abdesalem, a familiar figure along the Boulevard Mohamed El Hansali, a street on the Casablancan waterfront, had, with the great good fortune of a lucky lottery ticket, come up with enough money to travel to Europe to seek a job. He had come to Casablanca from his village as an ignorant peasant boy many years ago and now, in his mid-thirties, after a whole succession of livelihoods as servant, errand boy, shoeshine boy, fisherman, merchant mariner, sailor, docker, souvenir vendor and what not, he thought himself to be very much a man of Casablanca. He was a cheerful, easy-going man, kind to drunks and generous to beggars and over the years his fists, scarred on the knuckles with teeth marks, had earned him the respect of the streets. In turn, Barek loved the great sun-drenched port city, with its tall bleached white buildings, its mysterious Arab medina, the docks with their freighters and tourist liners, the fleet of Spanish and Arab fishing boats, the hazy skyline of giant derricks, forklifts and smokestacks.

M’Barek Ben Abdesalem, a familiar figure along the Boulevard Mohamed El Hansali, a street on the Casablancan waterfront, had, with the great good fortune of a lucky lottery ticket, come up with enough money to travel to Europe to seek a job. He had come to Casablanca from his village as an ignorant peasant boy many years ago and now, in his mid-thirties, after a whole succession of livelihoods as servant, errand boy, shoeshine boy, fisherman, merchant mariner, sailor, docker, souvenir vendor and what not, he thought himself to be very much a man of Casablanca. He was a cheerful, easy-going man, kind to drunks and generous to beggars and over the years his fists, scarred on the knuckles with teeth marks, had earned him the respect of the streets. In turn, Barek loved the great sun-drenched port city, with its tall bleached white buildings, its mysterious Arab medina, the docks with their freighters and tourist liners, the fleet of Spanish and Arab fishing boats, the hazy skyline of giant derricks, forklifts and smokestacks.

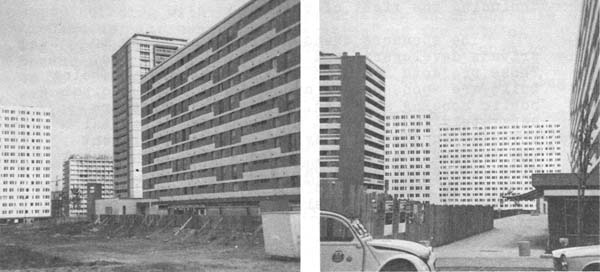

But in recent months, the city Prefecture had banned vendors from the pier, erecting a high steel fence to keep them out. Barek was obliged to give up his regular employment. He grew doll without work; whatever money he managed to earn, or the few dirhams a day his mother gave him, was spent on wine, beer or cheap cigarettes. His mother, the servant of a, French family for more than twenty years, was getting old and, ashamed of what few extra pennies she could scrape up and with nothing of his own to live on, Barek decided that as things were he ought to try and get to France or Germany. Hundreds of thousands of Arabs from the Maghreb now worked in the great automobile plants and coal mines of northern Europe, earning from $100 to $300 a month, and it was not without reason that most of Barek’s friends dreamed of going there. This meant obtaining a passport, not easy in the best of times, and to get the necessary papers, Barek returned to his childhood village.

Himself. “Hello, Baba! Hello, Baba!”

Barek took the little boy on his shoulders and went outside. In a few minutes, sitting on the edge of the steep riverbank, they watched the sunset and saw how the gold and crimson sky was reflected in the river, in the windows of the French manor house, and in the very air around them, which was soft and still and inexpressibly pure, as it never was in Casablanca. And when the son had set and the herds of cows and sheep went past, bleating and lowing, storks flew across from the other side of the river then all was silent; the soft light faded from the air, and the evening darkness rapidly descended.

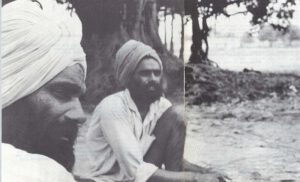

Meanwhile, the rest of the family had returned; Hadj, the father, a bent old man in a white turban and coarse wool jalaba; Mohamed, the oldest son, his handsome face already wrinkled and worn with hard labor-at the age of twenty-five; and the youngest three boys, Hassan, almost a man, and Abdullah and Ali. After they exchanged greetings, Hadj sent for some yellow mint tea in honor of the guest.

“Welcome, my son,” the old man said. “Look any time you are coming to our village. I must help you anyway Murhabani bicoum.” He asked Barek about Casablanca and said he himself had only visited the city once before and that was some years ago.

“I asked a man for directions on how to find a doctor. A friend in Romanni had given me the name and address on a piece of paper. After some time, walking through the narrow streets of the Medina, *I saw this man beckon to some friends. I feared the man was a bandit and told him to leave me. A shopkeeper who saw this told me never to trust anybody in the streets of Casablanca. ‘If you need something you mast ask a policeman.'”

“Ah, they are the worst bandits of all,” Barek laughed.

“The shopkeeper told me to get a water carrier to show me. I found the water place, a public faucet where the water carriers filled their goatskins, and an old man helped me find the doctor. But I was always afraid to go back to Casablanca.”

“There are many bandits there,” Barek agreed. “Many men go there from the village to find work and if they find no work they must steal. That is the life of Casablanca anyway.”

“But here also.” said Hadj. “In our village there was a man who with his wife, her sister and a child wanted to go to Rabat. They took 600 kilos of wheat with them for expenses. On the road they met a taxi and the man offered them a ride. After six or seven kilometers, the car stalled and the driver asked everybody to get out and push. They did and as the engine started he put on the gas and drove off with their wheat, leaving them behind.”

Everyone laughed, “Another time,” Hadj went on, a woman with a handbag with gold and a little boy went to some village. She found a taxi and the driver told her to get in. He handed her bag to a helper to pat in the trunk. When they arrived at the village the driver opened the trunk and found it was empty. ‘Oh, that son-of-a-bitch, my helper, I know him,’ he told the lady. “Look, you wait for me here. I’ll go find him. Can you wait for me here? Then the driver also left and didn’t return. How that lady carried on!’

*Medina is the Arab quarter; cashbah a word often misused means area of prostitution.

Hadj called to his wife, “What about the water, is it hot or not?”

“Yes,” she answered, her head in the door, “it’s boiling.”

Seeing his mother, Musa, the crippled child, said something in his excited, garbled tongue, which Barek couldn’t understand.

“He wants his hadoum,” Hadj explained, referring to the white hooded cape Moslem children sometimes wear at festivals. “He wants to dress up.”

“No,” said the mother. “He’ll tear it.”

“Just give it to him please.” said Hadj.

“Ya oulidi, my boy.” the mother signed. “The thing is torn.”

Musa, now angry, began loudly to demand the hadoum.

Hadj’s wife took a chest from under the bed and’ opened it, hunting through the ragged, threadbare garments. Musa, crawling to her side, saw the hadoum and began pulling on it excitedly. His mother released it from under the pile of clothes and the boy laughed as he draped it around his head.

“Mohamed, go into the garden to bring mint.” his father told him, Mohamed, always obedient as the eldest son, hurried to go but told Hadj, “Why you let Musa have that thing? He’ll only tear it.”

“Never mind. Let the child be happy.”

In a few moments, Mohamed returned with a sineya, or perforated tin basin over a large kettle and poured cold water from a big iron teakettle over Barek’s outstretched hands. He then brought a large bronze tray with seven glasses, a China teapot, lamps of white sugar in an ornamented tin box, a package of orange Pekoe tea from Singapore and a sprig of fresh green mint.

Barek, as the honored guest, was to prepare the tea and he gave his whole attention to it as the family watched. It was perhaps the oldest and most carefully preserved tradition in the Maghreb. First, he poured hot water in the teapot, removing half a glass to “clean the tea.” Then he washed the mint and broke it into small pieces and put them into the pot. Next he broke up the large chocks of sugar so they were small enough to push into the pot and then he poured hot water over them so that they melted like pieces of snow. With a certain solemnity, Barek poured a small amount of tea in a glass and tasted it for sweetness, then filled all the glasses, pouring from high in the air so that the hot liquid spattered and foamed as it went into the glasses. Finally he handed each male member of the family a glass with a blessing, “Hadj, bismillah,” “Mohammed, bismillah,” “Hassan, bismillah,” and the tray with the remaining tea was taken to the tent for the women and children.

The men drank the hot tea in silence, blowing on the surfaces and sipping with load, sibilant hisses. Barek repeated the process for a second round and then Hadj called to his wife, “Moujoud ayela? Is the food ready?” “It’s ready.”

The children harried outside for their own meal and Mohammed again brought cold water and a small piece of soap and a towel for Barek and Hadj to wash their hands. Then Mohammed set a round three-legged low brass table before them and a moment later set on it a steaming platter of tajim, a kind of stew with great chunks of beef heaped with potatoes, peas and carrots. Mohammed also brought a hot loaf of unleavened bread, which they used to sop up the gravy, eating greedily in their hunger.

After dinner oranges and more coffee were brought, which Mohammed loudly lapped up from a saucer amidst general silence. Barek was pleasantly drowsy by now and was relieved when Hadj almost at once began taking down the carpets and making up beds for the night. As guest, Barek was given the bed while the younger boys would sleep with him in the hat on the floor. Hadj and Mohamed slept with their wives in the black tent.

When the others had left, Barek lay down under a velvet comforter and in a sleepy, low voice told the boys about his life in Casablanca, his days as a seaman and how he hoped to go to Europe if he could get a passport. Hassan, the second son, a plump, lazy-looking youth, complained to Barek about the dullness of life in the village and told him in a confiding voice about his girlfriend in Romanni. He also said he had seen the gendarmes pass in a jeep along the road that afternoon. An old lady in the village has been murdered, stabbed to death, a few days before while gathering wood in a nearby forest. The most alarming aspect of the case was that her donkey had been stabbed to death too.

“Now why would anybody want to do that?” Barek muttered drowsily. They talked a little more and then fell silent.

It turned chilly, and near the hut a cock, crowing with all his might, kept them from sleeping. When the bluish morning light began to show through the cracks, Barek heard Mohamed get up and go outside, coughing and yawning and splashing cold water on his face. After a few moments, he brought two cows to the tent and his mother came out to milk them. Barek dozed off again and it was not until Hadj came to call the boys that he stirred himself to rise.

2.

Each morning Barek walked the four kilometers into the little community of Romanni, which housed the local administrative offices. There he visited the office of the Caid and the gendarmerie, applying for certificates of birth and residence. As he expected, it was a slow process. The Caid was away for some days, his application had been incorrectly filled out, there was an inevitable, “Come back tomorrow.” Barek found he was in no great hurry. During the late mornings and afternoons he worked in the fields with Mohamed, weeding, cultivating, cutting grass. And he enjoyed going back and forth along a little dirt road on the edge of the green valley. Sometimes, after he had stopped in at the Cafe Gaulois in Romanni for a glass of wine or two, he would stop along the way home and pick armfuls of wild flowers, daisies and poppies and the blue and lavender morning glories and sprigs of tiny violets. Barek did not know why he loved to pick flowers, but it became a passion with him as if one had to respond in some way to so much beauty.

The only small farm along his route belonged to Hadj. The rest of the land, planted in wheat and vast pea fields, belonged to a rich French landowner. Barek never saw the Frenchman but everyday passed a gang of fifty or sixty of his laborers, old men, women, girls and even children, who worked in his fields. Almost all of them lived in the douar, in the huts across the river. The able-bodied men among them did not join the laborers but formed small four-man crews along the riverbank shoveling sand from the river bottom, which they sold every few days by the truckload.

Sometimes Barek took Mohamed with him into Romanni. This day they were both in high spirits as they walked down the valley. Barek liked the wide sweep of the country, the clean air and the green, green color of the wheat and pea fields on the slopes and Mohamed felt that in the Casablancan he had found something close and akin to him. This day the son was rising. Low over the river skimmed a drowsy hawk. The river looked murky; here and there a mist hovered over it, but on the farther side a strip of light already lay across the hill, the tin roofs sparkled and in the olive trees of the French manor house the crows cawed indignantly.

“I heard it’s difficult to find work in Casablanca,” Mohamed told Barek, who agreed and told him he was better off in the village. Mohamed said he had been away only once, when the government called him to go into the army. He had taken the bas to Sidi Slimane and was to have stayed eighteen months, but he gave 10,000 francs to an official and the official said, “Okay, go home.” [In Moroccan currency, 100 francs make one dirham and 5 dirhams=$1] He said he stayed that night with some soldiers from Romanni; they got drunk on wine, told jokes and listened to Algerian records on a jukebox.

“Ya ben sidi ya khoua ya temgale marche

Rehe ou gole drete mara….”

Mohammed sang. He told Barek someone had told him about the singer, an Algerian married to a French woman in Paris. The singer wanted to return to the Maghreb but his wife refused and so in the song he lamented that “A man should have land, cows, money before he marries and he must be a man also.”

Mohamed said it was his favorite song. Near Romanni, nestled in trees at the bottom of the valley, white storks drifted through the air; they nested in the chimneys of the houses in summer.

“Tomorrow is market day. If father lets me I must take one sheep to the suq. [an open country market, held once each week] Anyway, we must go to the suq tomorrow together, Barek.”

“Inchallah.” [God willing]

They came to a broad, flat field of wheat where some fifty laborers were strong out, pulling weeds. Many of the workers were young girls in bright pink, red and yellow sweaters and scarves. The arrival of a visitor had become known in the douar and the workers stared with curiosity at Barek.

“Whose is this farm?” Barek called to an old man working nearest to him.

“It belongs to one Frenchman. Then that Frenchman went home and now he’s sold the land to another Frenchman.”

Barek stared at the workers sullenly. Then he suddenly exploded, “Why don’t they all go from here? So you people have land to live with!”

The workers just looked at him dally and an old, woman cried, “What are we going to do, young man? This is life. We have nothing to do. It has always been like this. We are, laboring people.”

One man, some distance behind the workers and apparently the overseer, now shouted, “Khademou! Arwa Khademou! Zido darea ya laire khademou! Sarbie! Quick! Quick! Get to work you people, quickly!”

The old man nearest Barek turned back and called, “Let the girls see the people. They want to marry.”

The overseer shouted back derisively, “With who are they going to marry? If they want to marry they must go look for somebody. Not in the working time. Now they must work quickly. We are not here for joking. This is working time.”

All the workers now stopped, amused by the diversion and the overseer swung a long stick at them, shouting, “Get back to work!”

Some of the girls giggled and the overseer sounded angrier than ever. “Watch the wheat! Watch and don’t break! Just easy, easy. Each one take his own rows. Take the grass with you. Don’t throw it on the ground.” The workers began to sing a sad song, one or two at first and then all of them together, a strangely sweet music, like a dirge and deeply moving. The overseer, swearing to himself, now came toward Mohamed and Barek.

“Salaam Aleikum,” he greeted them and then spat, muttering a filthy oath in the direction of the laborers, “I see you go by every morning. Why don’t you bring something from Romanni?”

“What I have to bring you?” Barek answered in a loud joking manner. “You need a bottle of wine?”

The workers laughed and the overseer reddened. “No, no wine. Bring something to eat. I don’t drink wine. I need something to eat.” He turned and strode back into the field.

“Why don’t you bring me a bottle?” cackled the old man. “I can get drunk with any kind of alcohol.”

Barek and Mohamed laughed and turned to go. “Salaam Aleikum,” Barek called. “La aonecome ibselama. God help you people.”

They came to the river. On the opposite side, Hassan, Mohamed’s brother, stood at the water’s edge taking off his clothes.

“That’s our Hassan,” Mohamed said. He called to him, “Hassan, did you take out the cows?”

“No,” his brother called back.

“Why don’t you take out the cows? I have to go to the village and you just stay here and swim in the river. Why don’t you do something?”

Hassan did not reply but plunged into the water and splashed about.

“Hassan is no good,” Mohamed told Barek. “Last night he came home at two or three o’clock. Father was very angry but he can do nothing with him. Always I must do the hard work. Any work at home I must do it. Anyway, I am the eldest son. It is my lot.”

Hassan’s dripping head emerged from the water not far from the bank. “I been out with the sheep all morning,” he said. “I’m tired. I was thinking about my girl friend all the time. Last night I went to the village to wait for her but she don’t come.”

“You must find her at the suq tomorrow,” Barek reassured him. “Don’t you worry.”

Mohamed and Barek walked along the riverbank until they reached the road to Romanni. Dew shimmered on the green bushes reflected in the water and the thousands and thousands of spring flowers along the sloping bank. There was a gust of warm air; it was soothing. What a beautiful morning. And how beautiful life could be in the Maghreb if it were not for poverty – terrible, everlasting poverty, from which there was no escape. Only to look around at the village was to realize how poor these people were, and the enchantment of the beauty that seemed to surround them instantly vanished.

When they neared the road they passed a young shepherd boy with a herd of cows who stared at Barek curiously.

“Salaam Aleikum,” Barek greeted him.

“Salaam Aleik.”

“These cows belong to you?”

“No. I’m alone,” the boy said. “No mother and no father. Before when my mother was alive I was in school. Now I work for this man for nothing. Maybe ten dirhams* a month. I’m just waiting to save enough money to take the bus. Go to some; big city. Get some school for free.”

“You’re just wasting your time here,” Barek told him, with some impatience. “Go quickly.”

“I wait to get some money to catch the bas and move from here. Go to school, go someplace where they teach some job.”

As they moved on, Mohamed said the shepherd boy was badly treated by the farmer who hired him. Yet without parents what could he do? And would the city be any better?

“Maybe yes, maybe no.” Barek said. “But at least there is a chance. Well, that is the life anyway.” And he told Mohammed how he had ran away from his village to Casablanca when he had been even younger than the shepherd boy.

“We had left here for El Jadida. It was a hungry time. We had about ten or eleven cows like this boy here. Sometimes I go with my mother after the cows, sometimes with my little sister. Sometimes I was so hungry I stole flour to eat. My mother would catch me and she would slap me. ‘Black boy,’ she used to scream. ‘Black boy, you are no good’ So, I stay two or three years like this. Then I leave my home. I leave my mother also. Like this shepherd boy.”

When they reached the village, Barek and Mohamed stood in the entrance of the Caid’s office and did not dare go farther. Finally, after an hour, a gendarme came and said the Caid was not in that day and to return tomorrow. They remained standing the whole time.

3.

That afternoon, Barek and Mohamed were cultivating the chick peas, one of them following the old wooden cultivator pulled by a male and the other going behind to pull weeds, when, a tall young foreigner with yellow hair drove up on a motor scooter. The two Arabs greeted the youth, who got off his-machine and offered them cigarettes. Almost at once Mohamed asked if he knew if anything could be done for his small brother, who “had no legs.” He invited the foreigner to the hut for tea and to take a look at Musa the crippled child.

As they walked to the hut, the foreigner introduced himself as Steve, and said he was an American with the Peace Corps. Hadj was waiting at the hut; sitting on a carpet spread out ever the grass on the slope above the river. He recognized the American as an agricultural technician working at the government research station at Merchouche, a village some ten kilometers away.

Musa came crawling oat of the cooking tent when he saw Mohammed and Barek coming and he scrambled onto Barek’s lap and proceeded to unbutton and button his jacket a corduroy sailor’s jacket Barek had bought in Amsterdam many years before.

Barek laughed and told Musa, “Hello, Baba,” and the child happily repeated the phrase over and over again. “Hello, Baba! Hello, Baba!” Barek had some chickpeas in his pocket and he put them in one doubled fist and held oat both for Musa to unclamp the fingers and find them. The child, delighted at the, game would shriek, “Hahia! Here it is! Hahia!”

His father, Hadj, delighted to see the child so happy, put two peas in his right hand, transferred them to his left, then very quickly pretended to blow on his fists. He gave the two fists to Musa to unfold, but when the child did so, all the peas were gone. Hadj chuckled and took the peas out of his mouth and everyone laughed at the trick.

*The equivalent of $2 per month

Musa clapped his hands together in delight but was so excited he bumped his arms, scarred with scabie sores, against his father’s legs and he began to cry. His eyes opened wide and large tears began to roll down his cheeks.

Barek took the child in his lap. “Well, Musa, please don’t cry. I’m going to take care of you, don’t you worry,” Barek took a towel and carefully dried away the boy’s tears and then gave him a glass of sweet coffee to drink. The child sniffled for a moment, then drank the coffee and forgot his pain.

“It looks like cerebral palsy,” the young American told Barek in English. “There’s not much that can be done but they should take him to a good doctor. With help, perhaps he could learn to walk.”

“But how?” asked Barek. “These are poor people.”

“How many hectares does he have?”

Barek asked Hadj in Arabic and translated, “Twenty-five.”

“That’s a pretty fair sized farm,” the American said. “Would he like me to have a look at his fields?”

After mint tea and some hot bread spread with melted butter, Hadj, Barek and the young American set out to see the fields. Mohamed had to take the donkey cart and cut grass down by the river.

Steve, the young American, first set out to establish Hadj’s costs of production and his methods and their offered advice on how they could be improved. But the conversation, conducted in a mixture of English, French and Arabic, proceeded in fits and starts.

“Le semence. Combien ce coute le semence? How much does the seed cost?”

Barek translated into Arabic.

“Vous parlez le semence…fifty five dirhams, which would be…deelu zera…super phosphate et la meelha…. See, I don’t know the exact prices for fertilizer. But I think it’s more. Hadj, le urea…le farina deelu…trois kilo…he has reason to….

“One quintal of nitrogen per hectare is enough,” Hadj said in Arabic.

“No,” Steve was emphatic. “With the new dwarf wheat you need two or three times that much. Two quintals. Maybe up to three. Dans une hectare…lektarekt*…une beau record….”

Barek: “Forty-five dirhams.”

“Ca c’est pour les ble dur. That’s for durum wheat. We’re working with bread wheats now. No, pas ca, le prix est trente-huit dirham par qu pour ble tendre parceque il n’y pas les variete de ble dur…Ah, thirty-eight dirhams. C’est officiale. Le prix de government.”

For some moments they all spoke in Arabic until Steve exclaimed, “Voila! Regardez, regardez!”

The Young American was able to outline what he considered the cost would be if Hadj produced the new dwarf wheat with modern methods of cultivation. This included $7.50 per hectare for a disc harrow if the tractor were hired by the day or $15 for two days’ work, $16 for seed per hectare, $14 for phosphate, $30 for urea, $2 for a-4-D herbicide, and $12 for the hire of a combine per hectare.

*hectare in Arabic

Steve estimated Hadj’s production costs if he used modern methods of wheat production would be about $89 or $90 per hectare. He explained that since the average yield per hectare for the new wheat could be expected to be at least 30 quintals and the selling price in the suq was $7.60 per quintal, Hadj would get a gross income of $220 per hectare minus the $90 for production costs or a net income per hectare of $138. How much was he getting now?

After another prolonged discussion in Arabic, Hadj figured he was getting $88 per hectare net profit by growing durum wheat. His yield of about 20 quintals or two tons per hectare was much lower than the 38 quintals possible with bread wheat but the market price was considerably higher, 44 dirhams per quintal as compared with 38 quintals for bread wheat.

Hadj argued that the higher investment wasn’t worth the risk, especially in a dry land, non-irrigated area where a farmer had to rely on rain. Steve suggested he borrow from the government.

“No, no,” Hadj was vehement. “If you rely on the government to provide everything so you, can use the modern methods, it will end up costing you ten times as much.”

“Hadj, he explain, a farmer, you know, he don’t take nothing from the government. He only work for himself,” Barek said.

“Even if he can make more?”

“Yeah.”

Steve was studying his calculations. “Je pense tout les figures c’est foog schweeah. Perhaps a little too high.”

Barek went on. “Hadj says he knows many people who have 150 hectare or so who get money from the government. The-man wants credit. He can advance something on his land and he takes paper to the government. The government must explain exactly and he pay the man. Now that man must pay back something every year. But maybe his crop fails. If he don’t pay he has twice as much to pay the next year. He has to pay double then.”

“If you, have ten hectares and you owe the government a million francs, well, so how do you sleep at night? Do you sleep or stay awake?” Hadj told Steve in Arabic.

Barek: “Hadj, he don’t want nothing to do with the government. He pay his taxes each year and that’s that.”

Steve: “Le government il a moyan de t’aider. It has the means to help you. To extend credit. Il peut aider.”

Hadj: “It can find out how much money you have and tax you more also.”

“Why don’t you buy a tractor?”

After a round of Arabic, Barek explained, “Hadj, he says people in the Maghreb don’t know how to work machinery. If you buy a tractor and you drive it ten or fifteen days, maybe it breaks down. And you have to pay someone to fix it.”

Steve: “It’s very important that someone in the, family has some mechanical ability. Perhaps the government could set up training centers for mechanics, the sons of farmers.”

Barek: “The government don’t know about such things. The government only knows how to tax the people.”

Steve: “If he buys a tractor, there are mechanics in Romanni. He can just ask them questions.”

Hadj: “If you have a tractor and it doesn’t work and you take it to a mechanic, maybe it’s just some small thing wrong but he takes it apart and you must pay him much money.”

As they talked they moved across the fields until they reached the end of Hadj’s land. Before them stretched the lash, heavily fertilized wheat fields of the Frenchman. Steve pointed oat the Frenchman was growing the new dwarf Mexican wheat.

“Look,” he told Hadj, “if you have one quintal for ten dollars and I have three quintals at five dollars and you end up with ten dollars and I end up with fifteen, which do you want?”

Hadj laughed. “Yes, it’s true. But you can’t sell this new wheat in the suq. Nobody will take it.”

“I’m exaggerating,” Steve went on. “Actually it would mean more like a 15 per cent cut in price and a 25 per cent increase in yield, with a net or 10 per cent more.” But to Hadj, as he told the young American, for a marginal dry land farmer dependent on rain he couldn’t take the added risks that the big French landowner could, even if it meant more profit.

Steve wandered out into the fields, at the point where Hadj’s land bordered the Frenchman’s. Steve called, “Hey, Barek, tell him this durum is very thin.”

Hadj explained there had been too much rain since January and not enough hot sun.

Steve disagreed. “Non, les population, le numbre des plantes per metre care. Maintenant l’augmentation c’est finie.”

Hadj: “Over there I didn’t use fertilizer; that’s why it’s so short.”

“The grain heads are too small.”

“When the sun comes, the grain head will grow big,” Hadj said.

“It’s either too light a seeding or a lack of rain in the fall so it didn’t come up. I’ll take a closer look.”

“This wheat belongs to the Frenchman.”

“It’s 3597, the Italian variety. La,la,la,la. [la” means no in Arabic] C’est ce Americain, le Mexicain.”

Barek: “Hadj wants to know what number.”

“C’est possible siete cerros.”

Hadj held up a bad plant.

“I don’t know,” said Steve. “Maybe no rain. Not enough fertilizer. There’s always something.”

Hadj: “It could also be that a donkey or cow stepped on it before.”‘

Steve counted the tillers of one row, first in Arabic than switching to English. “One plant has ninety-eight spikelets. It has five tillers or spikes or stalks and those five gave 98 spikelets. This has a genetic possibility to pat lots of grain on one plant while your 2777 duram doesn’t.” Steve tried to explain in Arabic to Hadj what he meant by plant genetics, finally giving up and saying, “If you put on a lot of fertilizer, it has to give you grain.”

Hadj smiled. “If you give the cow grass, he must give back milk.”

“Can yea explain to him, Barek?”

“I’m not a farmer anymore. He’s a farmer and you’re a farmer. If you want to know about village life, okay, I can tell you everything.”

“Well,” Steve said, “wheat in the Maghreb gives you, about 18 spikelets per spike, the same as Mexican. But Mexican gives you five or six tillers per plant while the old wheat only -gives you two or three. In America, in one test, they only used eight kilos of seed per hectare of Mexican variety and still got a good yield. Just eight kilos compared with the 140 kilos of seed Hadj uses. Barek, explain to Hadj. C’est une question de genetique.”

Barek was puzzled “Qu’est que c’est genetique?”

Hadj grinned knowingly. “The land. If you have good land, it will give you good wheat. The land is everything. This time before, in early winter, there was drought. Now too much rain comes. In Benimalal they have irrigation. M’zien bizef. Very good for the new wheat.”

Steve went on about genetics, saying they determined the length of the grain head, the shape of the grain head, the baking qualities of the flour, the ability to take large amounts of fertilizer without lodging. Finally he threw up his hands in frustration. “There aren’t the words in Arabic to explain genetics.” He playfully pulled Barek’s cap. “I’m trying to explain the difference in varieties and you don’t even know what a variety is.”

Barek pointed to a weed. “That’s also a variety. What’s its number?”

“It doesn’t have a number.”

“Sure. L’herbe savage.

They started walking back to the hut. Hadj told about a farmer in Merchouche who got 95 quintals per hectare with his barley, adding, “If I had pat in two hectares this year I could have given it to my cattle.”

“Why didn’t you grow it?” Steve asked.

“That man, he wouldn’t sell his seeds to everybody. He wouldn’t give it out. He was a Frenchman.”

Back at the hut Mohammed was waiting with mint tea. When Hadj went to wash, he joked with Steve, “Do you have a wife?”

“I don’t want a wife. I’m only twenty-two years old.”

“No, you must marry. You have to marry. You like Moroccan girls? Maybe I can find you a nice one.”

“Do you have a wife, Mohamed?”

“Yes.”

“When did you marry?”

“October.”

When Hadj returned, Mohamed was silent, as was the custom of sons before their fathers in the Maghreb.

Hadj explained to Steve why he was reluctant to obtain credit from the government or even get involved, with it in any way. Years before he had had a bad experience. He rented five hectares of his land to the French estate owner. The lease was to have expired in 1952, the year of Morocco’s independence from France.

When the time came, Hadj asked for his land back. The Frenchman refused to give it to him. He told Hadj, “Go and see the Caid, go see the government, go see whoever you want.” Hadj went to the Caid but couldn’t get a hearing; he suspected the Frenchman had bribed him. After two months he went to Rabat, the capital city, to consult the land office. For five months they pat him off, saying, “You wait, don’t worry. We’re investigating your case. Wait another month or two. We’ll call you.” After seven months and four trips to Rabat, Hadj returned to the capital and hired an advocate. He had to pay the lawyer 100,000 francs ($200) to handle his case. He was advised, “It may take as two or three months to get a hearing on your case. When we do, I’ll summon you.”

Two months later a letter arrived asking Hadj to be in Rabat on a certain date. The case came before the court and the judge asked to hear Hadj’s story.

“I’m not so poor,” Hadj told the judge, “but I need money. I have five sons, my wife, my brother’s wife and her children. So I need some money. So I gave five hectares of my land to this Frenchman for five years. The Frenchman told me, ‘I won’t give you land back. I have a contract with you to rent this land for more than five years.’ He told the judge the Frenchman had told him, ‘Go see whoever you want, go see the Caid, go see the government.’

Hadj told the judge, “I don’t want to make trouble. I am only a village man. I have lived there all my life. Many people know me and my father before me. The Caid wouldn’t hear my case and, I have come to Rabat many times. What can I do with this Frenchman? He won’t give me my land back.”

After hearing Hadj, the Frenchman was called to testify. He was asked to show proof that his contractual arrangement extended beyond five years. When the Frenchman could not, the judge ruled he must give the land back and the Caid was sent an order showing that Hadj could repossess. Hadj believed the Frenchman had banked on a simple villager’s inability to pursue the matter in the courts. Steve expressed surprise that the French could still own land in the Maghreb. Of course, they were efficient modern farmers and the government was concerned about feeding its people on a national scale. Still, it seemed to the young American, a vestige of colonialism. Like Barek earlier in the day, he thought to himself, why don’t they all go home and give these people land to live with?

4.

The suq, or country market, was nearly five kilometers away at Romanni, but the peasants went there every Wednesday to sell their wheat, vegetables, sheep, cows, camels or horses and buy clothes and provisions for the week ahead. In good weather, the girls dressed in their best and went in a crowd to the suq, and it was a gay sight to watch them crossing the meadow, some on foot and others riding donkeys, in their red, yellow and green dresses; in bad weather most of them stayed home. Then only the men went in their dark, hooded jalabas and heavy rubber boots against the rain and mud.

This day, Hadj and the younger boys had gone first, with the women and children, carrying 140 kilos of durum wheat on a donkey to sell in the suq. Mohamed and Barek, after putting the cows to pasture and leaving one of the boys, Ali, behind to watch them, followed behind. Walking was pleasant. The sky was a perfect blue and Mohamed and Barek were cheerful; everything seemed to entertain them: some men along the river shoveling sand into a truck; a row of telegraph poles running one after the other and disappearing over the horizon with a mysterious ham of their wires; the French manor house framed in its olive orchard and eucalyptus trees, uninhabited now but unaccountably happy looking, the daisies, poppies and morning glories, gleams of yellow, white, red, orange, blue and lavender in the green fields. And the sparrows chirped unflaggingly, the quails called to one another, and a donkey neighed as though complaining he was not going to the suq too.

Mohamed had risen before dawn to make mud bricks from the bank just across the river. He had completed 86 by midmorning, and now had 243 of the 800 he needed to build an 18-meter hut for his new wife. In his good spirits, he was telling Barek a religious story:

“Before, you know, Barek, there were no Arab people, only Christians and Jews. And Mohammed, he explained to them how we most have only one god. But when Mohammed told this to the people, that ‘There is no god but god and Mohammed is his prophet,” and that the believers must say one word, ‘sebhane lake,’ and he believe in god, the people, they turn against Mohammed and catch stones and throw them at him. ‘Go, go, you are not religion with Christian people.’ they said and they hit Mohammed with stones. Now Mohammed was with his cousin in the village where he lived selling dates. So Mohammed he marry with one woman, her name, Kadisha. So Mohammed went to some village and he bring Sidna Ali, his friend with him. Because Ali believed in Mohammed and the same god. One day they went to the mosque. The khafar people come after Mohammed and Ali. He like to kill him. God protect them with a magic wall and they escape from that village, from another gate. When they went oat, Mohammed and Ali, the Khafar people say, ‘Oh, these people from the Maghreb are sehara**

Just then they rounded a bend in the road and came upon the orphaned shepherd boy. Despite the sonny day, he was dressed in a heavy woolen jalaba. After greeting him, Mohamed asked him why.

“Today I was angry,” said the shepherd boy. “I wore my jalaba. I will work until evening until the farmer comes. Then I’ll tell him, ‘Pay me and I’m going off.’ If he pays me, maybe tonight, tomorrow, I’m going to leave for some big city, maybe Casablanca. Always I work hard hoping he’ll give me more! than ten dirhams a month. But nothing happens. So I’m going. Tonight or tomorrow.”

Barek thought for a moment of giving the boy some money, then thought better of it. He was a stranger in the douar now and it was better not to meddle in its affairs. As they walked on, Mohamed said the shepherd boy’s farmer had a second hired man who got sixty dirhams a month. “But he doesn’t work hard like the boy who must always go with the cows and cut the grass every night. Also he carries water from far away for the horses. But I doubt that he will go. Where can he go? Who will feed him?”

“Life is no good here in the Maghreb,” said Barek, who had almost forgotten he had no job himself.

Just then there was a great fuss across the river as one donkey tried to mount another. A woman rushed from one of the huts and angrily separated the two animals with sticks and stones. An Arabian horse tethered nearby tossed his head and reared up on his hind legs in the excitement. The steep riverbank was ablaze with spring flowers.

“Take the donkey off!” Mohamed shouted to the woman.

“Why don’t you come and do it!”

“It’s up to you; I’m across, the river!” Mohamed laughed as the woman shook a stick at him and began to sing:

River, go quick, my love does not come.

Where is she now? Where is she now?

The river flows by but where is she?

I hope she comes quickly, as quick as the river.

And I will wait till she comes, Habibti, Habiti.

**can tell the past and future; possess magical powers

+ khafar is used in Moroccan villages to mean “infidel” or unbeliever

Barek plucked a daisy, tearing the petals off one by one. “Katebhhiui kanebhika, she loves me, she loves me not…she loves me…” and the last, “…she loves me not!”‘

Mohamed laughed. “Why is it you’re not married, Barek?”‘

“No job. How can I support a wife? If I have a little money, maybe can buy a little house, maybe even a little carp then I will marry. Now maybe have money one day and nothing the next. That is not good if you have a wife and sons.”

When they reached the road a blue Ford tractor belonging to the Frenchman passed them and the Arab driver stopped and offered them a ride.

“Salaam Aleikum. Labas,” Barek greeted the driver as they climbed on behind.

“Labas.* Ca va?”

“Ca va bien. Hamdullah.

“Where you go?”

“To the suq.”

The driver nodded and the tractor pulled ahead. “Ah, God save us,” the driver lamented, glad for an audience. “These days the people in the Maghreb are no good. All are bad people. Some rich man they hire poor men but don’t pay properly. Always argue. Always fight. If you want more money, he take you to Caid, maybe take you to jail.”

“You work for the Frenchman?”

“So I do and I’m always angry with him, the French landlord. But what can I do? Maybe he’ll take me to the Caid, maybe to jail. We wait for Allah to judge them. The rich man has a lot of money but he want to eat the poor people anyway. How can we live? The rich eat the poor.”

Along the road ‘streams of villagers were moving toward the suq, many of them walking but some on horses, mules and donkeys. Barek had not been to a country market for years and he felt the old thrill of excitement he had experienced as a boy as they approached the great tent city that had been erected for the market day.

Thanking the driver, they dismounted from the tractor and hurried toward the suq. Near the entrance gate, a young man was lying on the earth, rolling back and forth in a drunken stupor.

“This boy he hate his life maybe,” Barek told Mohamed. “No work. No job. He buy twenty francs, thirty francs, alcohol to make fire with. Always he like to kill his self. I see many such men in Casablanca.” The two watched as a group of gendarmes, impressive in starched grey uniforms and polished black boots, approach the youth and pull him to his feet. The youth had stuck pins in his cheeks and was bleeding from his forehead. Two of the gendarmes pushed him ahead of them, kicking him with their knees when he started to stumble and fall again.

“The gendarme don’t like he stay in front of the suq,”‘ Barek went on. “See how they kick him and slap him to wake him up. Some people have blood no good. Too much alcohol. I think he hate his life. No good clothes. Maybe no eating every day. He do these things. He think maybe somebody help him. Take him to the hospital.”

Now they were inside the suq and they soon forgot about the drunken youth. All around them was a scene of great bustle and confusion. To one side were the cattle yards where men were trading horses, cows, goats and sheep. Beside it, under a great covered shed was the slaughterhouse with fresh meat. Barek noticed several bloodstained goatskins lying about on the ground and here and there a skull or a half-crushed jawbone with teeth still set in a ghastly grimace. In a score, of gaily-draped barbers’ tents, peasants were being shaved. There were hundreds of tents selling everything imaginable: women’s clothes from black jalabas to diaphanous pink silk sleeping gowns; men’s jalabas, spices, herb medicines, butter and milk, carpets, dishes, pans, lamps, plastic basins, children’s toys, eggs, spices. There were row upon row of cobblers’ shops, stalls of fruit and vegetables heaped high with cabbages, carrots, beets, lettuce, potatoes, oranges, apples, lemons, everything one could desire. Everywhere there were people, the men in their long, flowing jalabas, the women in bright silk gowns worn one atop another so that many had on as many as five or six. Weaving through the crowds were watermen, carrying their heavy wet goatskins and wearing gaily decorated large straw hats. A group of telba fahramasekin, tall holy men in hooded black cloaks, went front stall to stall reciting verses from the Koran and holding out their hands for alms in an oddly menacing way. Big muscular men who resembled gangsters more than priests, they cried in gruff, threatening voices: “Please for your mother, if she’s dead; for your father, if he’s dead. Please help us.”

*Labas is used interchangeably both for “How are you’?” and “Fine”

At the covered wheat market, Mohamed and Barek stopped to search for Hadj and the family, but they had apparently sold their wheat and moved on. As they stood there, they watched a woman with heavy black kohl lines drawn around her eyes, bargaining with one peasant. The woman picked up a handful of his wheat and sniffed it disdainfully three times before asking the price.

“Eight dirhams,” said the peasant.

The woman moved on without a word and threw more came up and they too gathered up some grain in their palms and sniffed it. “This what is no good,” complained one. “Very old. It’s been stored underground.” She moved on to the next peasant and, finding his wheat had no odor, told him to fill her sack. He used a six kilo tin can to scoop it up with painful care lest it be too fall or too empty.

“Full, full, make it full,” cried the woman. “Don’t cheat me or yourself.” Then she complained he was taking too much time. “Hurry. Quick. We have some more things to do.” Just then another woman came running up and shrieked, “I can’t find my donkey. He’s wandered off. Here, keep my wheat for me while I find him.”

All around them the bargaining went on. “How much?” “Seven dirhams.” “That’s too expensive for us. If you give it to me for six dirhams, okay…. If not, well….” “No, you must give me seven.” The customer turned to walk away. “Look, I can’t sell you for six. If you pay six and a half, okay. This is good wheat. Some will not sell you so much for eight or nine dirhams.” Again the man turned away. “All right, take it for six.” “Wakha.” [okay, the word is pronounced very gutturally]

They heard another peasant’s wife complaining, “What are we going to do with this little bit? You sold all but two kilos.” “We’ll just have to take it home again. Here, put it in the saddle bags.”

Mohamed and Barek wandered over to the cattle market, the most exciting place in the suq for sometimes real fortunes exchanged hands and sharp traders acted as go-betweens for the peasants for a commission. The market was in a large yard, jammed with goats, sheep and cows and groups of excited men, gesturing, uttering oaths and filthy insults, gathering arms on each others’ shoulders for whispered conferences and roars of laughter and approval as bargains were sealed.

One prosperous red-faced farmer in a green jalaba wanted to buy a fat brown cow with calf, and was surrounded, almost bedeviled, it appeared, by two lanky sons and three men in dingy white turbans and brown jalabas who were acting as go-betweens. Another buyer, who had apparently lost out in the bargaining, shook his fist at the cow’s owner, shouting, “I’ll come next week and buy better than your cow for 50,000 francs!”

The owner, a sun burnt young peasant, called after him, “How can you find like this cow? It has a calf inside. A strong cow. A good cow. And you think you are going to find another like it in the suq? Well, go, my brother, go and see if you can find next week. I don’t want to sell for only 50,000”

“I’ll give you 55,000,” called one of the traders with the prosperous farmer.

“I don’t sell for 75,000.”

“Well,” said the trader, undeterred and waving a 10,000 note in the owner’s face, “here’s the advance. Leave it to me for sixty.” The stout farmer prodded the cow in its belly, opened its jaw and studied the teeth. Another whispered conference with his sons and the traders followed. “Ah,” groaned the farmer. “This is a bad suq. Bad business. I offer him a fair price but he won’t see me for 60,000 francs. So what can I do?”‘

“Well, pay more,” one of the traders advised him in a wheedling voice. “A calf is on the way. Give him a little more and he’ll sign the contract right away.” The farmer finally agreed and both he and the owner went to a government shed to register the bill of sale. The owner gave a fifteen dirham commission to the three traders but the buyer only gave them ten.

“What are we going to do with ten dirhams?” one of the traders complained loudly. “We are three men.”

Mohamed and Barek moved along, passing a forlorn trader who had bought four black goats and then could find no one to bay them again, “He must wait for the next suq,” Mohamed laughed. He said his father used to be a cattle trader in his youth; there was good money in it, especially selling cows and horses. A man could earn as much as 200 dirhams in a day. Sheep and goats also yielded a profit but a donkey went for only 30 to 35 dirhams, barely worth the trouble.

As they moved back to the tent city, a car moved, slowly through the crowd, almost bumping an old lady on a donkey. The driver, a young man in a suit, was angry, “Why don’t you people stay on the side where you belong?” “Aaagh, that’s a bad one that is,” screeched the old lady after him. “What does he want me to do? Does he want the whole road to himself?”

Heading toward the tea tents, where a bamboo mat and hot water was provided for a dirham, Mohamed and Barek stopped to buy tea, mint, sugar and order some mutton brochettes and bread. As Barek made the tea, Hassan and another youth from the douar, came up to join them. A plump young village girl, her face halt hidden by a black scarf, called after Hassan, “Bring some bread back with you.”

“What I’m going to bring bread for?” he asked, then grinned slyly. “You want Arab bread? Or French bread?”

The girl laughed. “Just so it’s hot.”

As she disappeared in the crowd, Hassan and his friend speculated whether the girl “did business” or not.

“She’s very young for the business,” said the friend. “But maybe. What about your girl friend Hassan? She with you now or not?”

“Always she is with me.”

“Oh, mine,” groaned the friend. “I’m going to change her. I have another one in mind. Let’s go see if she’s here or not. If not, we’ll meet here in Romanni tomorrow. Then I must talk with her. See if she likes me nor not. If she’s all right, we’re going to have a party together. You and I and the girls. Besulama.”

Mohamed greeted two peasants from the douar who had come to the tent to make tea. “Give us you tea and mint and we’ll all drink together,” he joked.

“No. Shove off.” His friends laughed. “Move. You drink your tea. Finish. You must go. You and your friend.”

“Look at the poor man,” Mohamed said in a quavering, theatrical voice. When his friend called for hot water in a simple, peasant manner, Mohamed made fun of him, “Why you talk like that? You think you’re back in the douar?”

Hadj, who had been searching his sons, came in and sat down beside them. He said he had sold his 140 kilos of durum wheat for 80 dirhams. “Only seven customers. It took less than an hour and a half. Here Mohamed, You take 30 dirhams. I owe you. You, Hassan, take this 40 and go buy meat, potatoes, tomatoes, onions, carrots, three packages of tea and eight kilos of sugar. When you buy you must count exactly what you spend for everything and report to me.”

Hadj joined some older men from the douar for tea and Mohamed and Barek went to buy some things for Mohamed’s wife: henna to dye her hands as was the fashion in the Maghreb, a pair of red silk pantaloons for seven dirhams, a nightshirt for Mohamed, a meter of white cotton cloth to make headscarves for his wife and mother, a pair or rubber work boots for twelve dirhams, a pair of work pants, two boxes of Tide laundry soap, two bars of washing soap, tobacco for self-rolled cigarettes and a sack of candy and peanuts for Musa. By the time he had finished, Mohamed had only three of the thirty dirhams left. “Look, Barek,” he said, “I work hard, very hard. I save up this money for a month and I come to the suq and spend it all in one day.”

Barek in turn bought twenty dirhams worth of groceries, including chicken and mutton, and a shirt, a pullover and a small pair of pants for Musa. Elle also spent a great deal of money giving small change to each of nearly a dozen beggars who came along.

“Why you always give to those people?” Mohamed asked him.

Barek shrugged. “Well, it’s just this way. Anyway, I must give.”

When they rejoined Hadj at the tea tent, Hassan was also just returning. He told his father he had spent thirty-three dirhams and twenty francs. When he enumerated what each item had cost, Hadj groaned, “Prices have never been so high at the suq. Perhaps it is all the rainy weather.” But, as Mohamed told Barek later, Hadj knew Hassan kept a small commission on what he bought for the family. But he never said anything to the boy.

“Where’s the rest of the money?” Hadj asked.

“I have it in my pocket.”

“Keep it until we reach home.” He sent Mohamed to fetch the family’s mule and gave him 30 francs to pay the watchman. Then Hadj loaded the groceries into saddlebags and he and Hassan took the male home. “Are you coming?” he called over his shoulder to Mohamed.

“I’m going to lauch with Barek. He asked me to join him.”

“All right. But you must come home early. Don’t leave me to wait for you. You have to take the cows out, cut grass, so many things.”

When his father was out of earshot, Mohamed muttered, with a note of real weariness in his voice, “Travaille, travaille, toujours travaille.”

Mohamed’s spirits rose after the first glass of wine, at Romanni’s only restaurant; he had never been inside it before and the Arab waiter seemed to be only half-joking when he placed a white linen napkin before the young peasant and whispered, “Don’t steal it.” Between them Barek and Mohammed finished a bottle of wine over their roasted chicken and pomme frites, and hearing men singing and playing the accordion at the tavern across the road when they came outside, they went over to the Cafe Gaulois for two more rounds of wine.

“Khaife alic la adebouc,” Mohamed sang as they headed home in the afternoon sun. “Achire klaife lamaheuoc a sidi. Ya habibi dini mal dini mal. I love my wife, so I must work hard in my fields so I can go the suq and buy her presents.” Mohamed improvised the words as he went along. Despite the bright sun, a chill wind seemed to be rising from the north, toward the Atlantic.

“When it’s cold like this, it will bring rain tonight,” Mohamed said.

“Yes,” Barek agreed. “The radio forecast heavy rains for tonight. The bartender told me.”

Ahead of them on the road two women were walking and the wind carried back their shrill voices.

“What have I still got to do today?” said one. “Don’t ask. I have to dry wheat, wash clothes, cook dinner for my husband. I’ve got so much to do I don’t know where I should start. I stayed too long at the suq. How about you?”

“I have to cook something for my husband.”

“Look, look,” said Mohamed, pointing to a distant, figure down along the river. “That’s the man who sells kif.” [hashish]

“How green the valley is,” marveled Barek. “It is lovely, this valley of yours.”

“But too much rain. Too much rain this year.”

The meadows, the hills, the bushes near the river seemed a vivid, unnatural green in the afternoon light. The sun, moving in its are, toward the western horizon, flaming pink the magnificent clouds overhead, gave to the valley something extraordinary, novel and improbable, the sort of intense, vivid color that seems unbelievable when one sees it in a picture. Swiftly, swiftly flew the storks, with mournful, mysterious cries. Barek paused at the top of the slope and gazed for a long time at the green valley, at the sunshine, at the family’s humble farmstead, which looked bright and, as it were, rejuvenated; his eyes watered, he gasped for breath, so passionate was his desire to stay, to find a life for himself in this beautiful place; yet he knew he must go. Where? Maybe even to the ends of the earth, Poor he was, as poor as Mohamed beside him. But he was free and go he would. And suddenly he wanted to get away quickly.

“Hamida! Hamida! Come here!” Mohamed was calling to a tall, scraggly, scarecrow of a man who had appeared oat of the Frenchman’s olive grove. “Hamida,” he told Barek, “has a house, a guitar and can fix a man up with girls. He is a pensioned off soldier who served in Indochina with the French forces.” Mohamed tore off a sunflower from its stalk along the road and put it on his head like a hat.

They reached Hamida, whose old, grizzled face grinned at them. “Salaam Aleikum.”

“La bas?”

“La bas.”

“Do you have some wine?” Mohamed asked.

“No, not yet. But you like coffee? Or tea? Come to my house.”

Hamida’s hat was third from the end of the douar and seemed the meanest and poorest looking. It had a metal roof and grimy curtains at the windows but otherwise had a dirty, unkempt look with its spotted carpets and a grimy, uninviting bed.

“If you need a woman or something, you can come here,” Hamida told Barek.

“If you like to live with him, Barek, just find some woman to cook for you and you can live here with Hamida. He fought in Indochina.”

“Now my life is wine,” the old man lamented. Now I don’t marry. Not now.” He turned to Mohamed. “Get two glasses from your house. I haven’t enough.”

“No, you do your business. You invited as for tea. You must bring.”

“I have only two glasses,” Hamida apologized. Mohamed took the old man’s billfold and began looking through it. He found a few dirham notes “Monsieur Hamida, il est tres riche.” Hamida showed Barek his old army discharge papers. In a faded photograph he appeared young and handsome.

“Put everything back,” Hamida told Mohamed. “Don’t be like a small boy.”

“Don’t worry. I’ll put everything back as it was. Ah, here’s some snuff.”

“That’s another kind,” the old man said, taking a packet from his pocket and whiffing it. “I’m using this one now.”

“Quick. Where’s the tea? Because we have to go all the way back to the bridge. We don’t have time to spare.” I won’t take you with me to cut grass today, Barek. The grass is wet.”

“No, I’ll go.”

“Where’s the tea?”

But instead Hamida produced a large bottle of wine from under his bed and with a practiced movement, pulled out the cork with his teeth. He poured them two glasses, than produced some kif and for a moment they were silent, poking the dried green hashish into their cigarettes. As they smoked, the room filling up with the pungent, sweet odor, Hamida explained how he had once been happily married and with a good job for the Frenchman. But that was long ago and now he earned only a few dirhams from his pension and shoveling sand from the river bottom. “We have teams of four men each,” he said. “A truckload brings in twelve dirhams, that’s three apiece. One day maybe a man can make twenty dirhams, maybe a weeks, nothing. Now the river is too high. The current takes all the sand away. It’s hard work but it’s sometimes good money. In the rain this week, the water rose and carried off all the sand we’d been piling up for a month. Here, have some more wine.”‘ The old man himself drank right from the bottle. When it was quickly emptied, he pulled another from under the bed. “I get credit from the tavern,” he explained.

A mongrel dog poked its head in the door.

“It’s a bad dog,” Mohammed said. “Very vicious.”

“It looks like a wolf,” said Barek.

“How’s my army pictures? Nice or not?” Hamida asked.

“You look handsome,” Barek reassured him.

“I get these bottles from Lucien, the bartender at the, Gaulois.” The old man signed. “Now my life is wine and meat. My wife made the business with other men so I left her.” He emptied the wine bottle in their glasses and rummaged through the blankets on his bed for a third. It was cheap wine, Barek knew, the kind that only cost two and a half dirhams a bottle.

“We never had so much rain as this year. Never.” Mohamed’s words were now beginning to run together. “Barek, you see the life in our douar. What you think, this good life or not?”

“A good life, if a man has a little money.”

“What about your life? Tell as about Casablanca. You said you ran away from the douar when you were just the age of that shepherd boy. What happened then?”

“My life?” said Barek with surprise, as if he had never considered the question before. “There’s not much to tell.”

But he found himself speaking and not stopping but going on and on, as Hamida filled the glasses once more and someone passed around the hashish.

“Maybe I was eight or nine years old when I ran away. ‘Hey, black boy. Hey you black boy.’ I can still remember her saying and slapping me because I was into the flour. I was so hungry.

“The first few days in Casa I don’t know where to go, what to do. I never even had a pair of shoes on in my life. I got a job one week in a cheap restaurant. Slept on the floor. Splashed some water on my face to wash. Never changed my clothes, I never used a toothbrush until I was seventeen years old. This cafe gave only food, no money. It was only a small cafe, for poor people. I ran away because I was pissed off with my mother. Each time she hit me.”

“What about your father?” Mohamed asked gently.

“My father? I remember him when I was six years old. But when he dead, when he die, I don’t see him. He died after I ran away. He was angry with my mother and left her. I was only showed the grave many years after.

“We were four boys. Abdesalem, he works now in a place in Casa crating fruit. He’s three or four years older. Tall, fair, looks like a white man. My other two brothers are farmers. One has a few hectares, the other works in a labor gang for some rich Arab. He sold his land and now he’s only a laborer for some other man. But my brother Mohamed he’s got cows, sheep, land, wife, good house, like you.

“In Casablanca I found a job with a man who worked for the government. He gave out marriage certificates. A rich man. He had a big son in school, maybe 18, 19 years ago. That boy, he don’t like his father. Always they fight because that son, he like to go with boys, not girls. But that man, my boss, always he was good to me; sometimes he take me to movie. Each holiday. He don’t like his son so he treat me good. He send me to school for five years to learn French. I go to market, buy bread, get some legume. I was kitchen boy. I worked for that man for seven years. Always he like me, take care of me. He saw me two or three times in the street before and one day he came and asked me, ‘You like to come and work for me in my house?’

“My oldest brother, Mohamed, after seven years, he finds out that I work for this man in Casablanca. He waited for me one day when I went to the market. Kissed me on both cheeks. The man I worked for, I told him had no family. When I went with my brothers, he see and think they want to kidnap me. He telephones the police station. The police take my brothers to the station, but I identified. My family wanted to take me away so we went back to El Jadida for a month and I stayed at the house of my uncle. At that time I am about 15.

“After one month and one day I ran away again to Casablanca.”

“Why?” Mohamed asked, appalled by the idea of leaving, one’s family and village.

Barek took a long swig on his wine and Hamida harried to fill it up again.

“I love Casablanca,” he said. “I don’t like to sit in a small village like this. Why? Why? I don’t know why. That’s the way it is anyway.”

“But that man sent you to school?” Mohamed asked.

“Yeah. In the morning before I went to the market and bought hot bread. In the afternoon, he sent me to school for four years and six months. I learned Arabic and French but the master in Arabic always hit me. French was easy. But I couldn’t do Arabic. Oh, that son of a bitch hit some of the boys also, but me, always met he beat very much.”

“In the Maghreb if a father has money he can send his sons to school. If he is poor he most send them after the cows, after the sheep.” said Hamida sadly.

“Father sent me to French school for four years and now Ali is going to the Arab school. But Hassan and Abdullah never went because the king said if a man has many sons he doesn’t have to send them all to school. Only some and some should stay and farm and one or two go to the town to learn a trade. So father follows the king,” Mohammed explained.

But Barek was now in a reverie of his own, remembering.

“Back in Casablanca I found a place where there were three French whorehouses. Many seamen, many cars stop there.”

“Why didn’t you go back to your old master?”

“He was angry because my brothers took me away. I never saw him again.”

“And then?” Hamida was interested now.

“I’d wait at the cars in front of the whorehouses and when seamen came out I said I was the watchman. I cleaned the windows on their cars and they gave me ten, twenty francs. Then when I had enough for a movie, I’d go. A few years later my mother came back from El Jadida. My father had two or three shops she rented out and she got two rooms in Casa near the port and a job as a cook with a French family. She’s stayed with them ever since, just goes back to the village for the wheat harvest.

“You ever go inside those private houses?” Hamida asked.

“Sure. Sometimes. The old French madam, she liked to joke. Then she heard independence was coming and she got out. That was when the king closed the casbah. So I got a job at the fish market. I don’t like that other job. If you do like this, always hanging around the private houses like that, sooner or later you must be a pimp. So I got a job on the fishing boats and finally joined the merchant marine. After I got out they gave me a seaman’s book so I took a job on a Greek ship. I was galley boy. We take phosphate to Amsterdam and Rotterdam. I was galley boy, serving seaman people. Got paid twenty-eight English pounds a month. One day I was late for work in Dieppe, in Norway. I got drunk. We had a fight so I was angry with the captain of the ship. For seven or eight months I don’t work but before I sent money to my mother, maybe seven pounds a month, sometimes ten.

“Then I got a job on a French cargo ship. It took oranges and tomatoes from Casa. The pay was 32,000 francs a month. I was galley boy, this time for officers. We went to Marseille, then back to Casablanca. Down the coast to Porlioti, Khinitra, back to Marseille again. When they paid me off, I stayed on dock as a watchman for the same company. Sometimes I work three or four days as watchman, the rest of the time I sold souvenirs to the tourist people and sailors. But now the Prefecture won’t let us on the pier. So…that’s the life.”

“How’d you like those foreign countries?” asked Mohamed, who had never even been to a city.

“Many good people, gentle people, everywhere help you, joke, good places, not same us. Good cities, good countries. All of ’em intelligent, all of ’em have a job, they work, so…this way. Not all the time poor people. In Marseille where there’s many Algerian people, they can stab you with a knife. Some French are gangster too but they steal the big things you know, a million.”

“How’s Casablanca? Is it easy to get a job?”

“La. Some people, many people, they don t work. If a tourist or seaman goes into the medina, well, maybe he lose his money. If have no money, well, maybe somebody do something to him, maybe beat him. Well, it’s this way, anyway. That’s the life of Casa.”

“Sometimes, a man’s as good as dead,” sobbed Hamida, a tear rolling down his drunken, grizzled cheek.

“La, la, ” said Barek with some vehemence. “It’s like, how can I explain? My father, he’s in some die place. He stays there until all the world is finish. Then you must wake up again. Allah must see who’s the best, who’s the bad. This way everybody has to pay for his life, if he’s nice or bad.

“If he’s nice, he has to go somewhere, somewhere where he has a good time. If he’s bad they have to put him in the fireplace. The God speaks, not as. The Koran, we hear about the Koran, it speaks this word, not us.” Nervous at so much speech, Barek growled at the dog, but he could not stop himself from going on and he downed another glass of wine at a single gulp.

“Hadj, he has enough to live on with you, Mohammed, his sons and his land. Not like the Casablanca man. The Casablanca man if he don’t make no money in a day, he can’t even have a coffee to drink.”

Mohamed watched him solemnly. He asked, “What you want out of life, Barek?”*

Barek answered right away. “I like to work hard, someplace where I make good money to live with that’s all. I like to live good, eat good, have good clothes. I like to have sons, a car, if possible a home. This way. The best thing I want – I want to go another country. Life is too hard here.”

They drank to that and sobered by Barek’s story, Mohamed began to rise to his feet. But Barek raised his hand and said in a quavering, drunken voice, “Wait! You want to hear the rest of my story?”

Mohamed sat down again. Hamida lit another stick of hashish, inhaled, drawing the air in between his teeth, and passed in to Barek. The air of the dim, cramped hut was now heavy and sweet with the odor of burning hemp.

“I have a brother in Casablanca,” Barek began. “Abdesalem. He’s a workingman to one company. Oranges, tomatoes. So my brother, he makes about forty dirhams in the week and he don’t drink also. He don’t drink and he’s married now, three times. He had no boy, no children, only him and his wife. And always he’s angry with his wife.

“My brother, he play cards, you know, for money, gambling and sometimes he spends his money and comes after his wife; he takes her bracelets, rings, carpets, clothes and sells them. Because he plays cards so much. So he comes late at home, tow or three o’clock in the morning. Ever time he come late.

“One time I was working as a seaman. Three years ago. I am seaman with this French ship. Here in Casablanca, if you drink, you don’t drink in front of your mother. Like in the village. If you want to drink, you can catch a room, $6 a month, you can have it. I leave my good clothes, blankets, all the house things to this room and I go to sea. From Marseilles, I send my brother a letter, ‘You must take care of my room. Go take a look to see if it’s all right. Get the key from the shopkeeper.’ One day I came home to Casa and I go to my room and found the clothes gone, the blankets gone. Somebody else is living in the room. Where I been. ‘Who are you?’ I asked this man in the room. He say, ‘Well, I’m…I find the landlord’s house and he give me this room. Six dollars a month.’

“This is my room. I’ve been at sea.’ Then the boss came come and told me, ‘Well, your brother took all the things you left here. Then he gave me the key and he go.’ Now in that room I leave six or seven pairs of pants, three or four towels, some stuff to cook, pots and things, ten shirts, three blankets, one mattress, one bed, table, chairs to sit on, everything I got in the world was in that room. I went to my brother’s house but he’s not there. I found only his wife. She kissed me on both cheeks and she cry. And she explained to me exactly what he was doing before to her. He hit her, slap her, don’t give food to her. Sometimes he don’t come for two or three days. Take her gold bracelet, sell his radio. She told me also sold the gold tea tray, copper candlesticks, everything. I asked, ‘Where’s he now?’ His wife said, ‘He’s at work now.’

“And I go to his company and I asked one man to call Abdesalem. So my brother’s coming to me. He kissed me also on both cheeks. I think I must be wrong. I mean, when he kissed me like that I think he must no do anything wrong. I think I make a mistake. So I asked, ‘How about my room?'”

“Your room? The landlord took it back.”

“How he take it? Then you gave him the key?”

“He asked for the key. The landlord asked for it. So I gave it to him.”

“How about my clothes and my bed? How about….”

“You know my house is too small. I don’t have no place to keep it. I sell it.”

“You sell all? My clothes to wear too?”

“When the landlord come and asked for the key,” he said. “You gotta pay me or give me the key. This way I don’t have no money to pay the man for six, seven months for you. This way I took the bed, clothes and everything and I don’t have no place to put. That’s why I sell to somebody.”

“How much you sell it? All those things? My bedroom, my clothes.”

“I got 250 bucks.”

“Who give you leave to sell like this? Who told you to give back the key? I ask you to look after the room. You are my brother. And you do this thing to me. Sell my clothes. Everything I got.”

“When this man come to take his key, he said, ‘You have to take this furniture and clothes and keep or sell until he comes.”

Barek paused. “He’s many years older than me, my brother. Always I respect him, look up to him. But that day I punched the son of a bitch in the face, I knocked him down. He was bleeding and I hit him. Then I told him he must bring my clothes back, my bedroom back.

“Well I sell all the things.’ he said. ‘Now if you want me to give you the $250 back, I give you.”

“Okay.”

“Well, I don’t have one penny now. You must wait each week. I give you five bucks a week.”

“I wanted to kill him. But I think, he’s my own brother. He does this thing. But he’s my brother. I can’t do anything. I promise you this is true. So I never see him. I don’t take one penny from him. It’s about three years I don’t see him. Even my mother, she don’t like that man. He stealing from her before. His wife was always nice to me but that son of a bitch is no good.”

“It’s cold,” Hamida murmured drunkenly as he stretched out on the carpet that covered the damp floor.